This is the second story in an ongoing series on conviction review units and the people and organizations fighting to free innocent people from incarceration. Read the first story here.

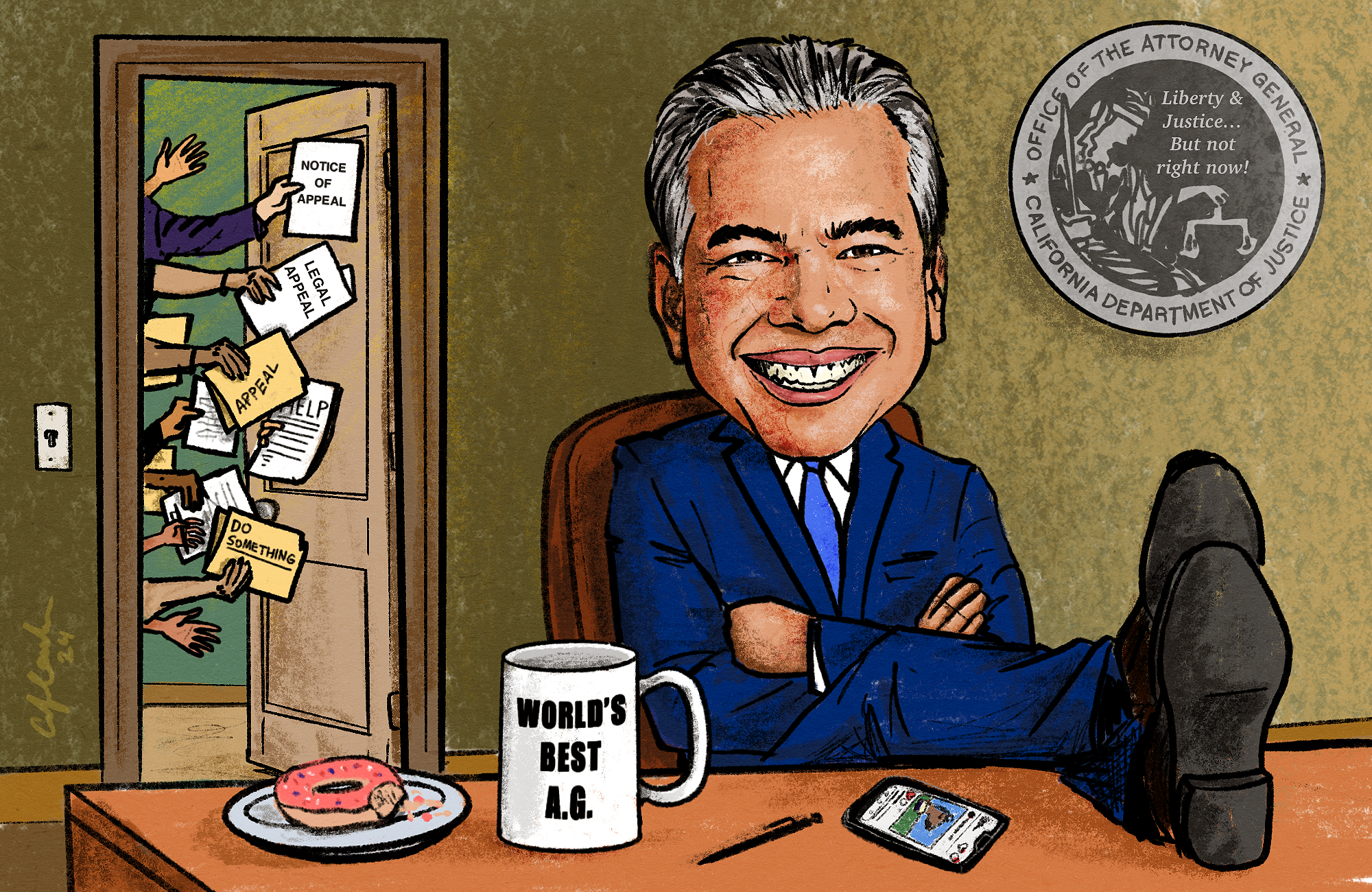

When California Attorney General Rob Bonta launched the state’s first conviction review unit in early 2023, he promised to investigate claims of wrongful convictions and cases in which new evidence cast doubt on guilty verdicts.

“Nobody should serve time for a crime that they didn’t commit,” Bonta said at a February 2023 press conference announcing the “historic unit.”

But nearly two years later, not a single person has been exonerated or resentenced through the AG’s Post Conviction Justice Unit (PCJU). In fact, the unit hasn’t even started accepting applications.

A spokesperson for the attorney general's office declined to answer a list of questions from L.A. TACO sent via email in September.

In a statement, the spokesperson said: “PCJU is currently developing protocols for case intake, investigation, and evaluation. Since they have joined the DOJ team, our two PCJU deputies have been examining conviction review protocols throughout the country and meeting with a wide variety of stakeholders, including local prosecutors, innocence projects, victim advocacy groups, non-profit groups working with incarcerated people, and other state officials. In December, PCJU hosted the first statewide Post-Conviction Justice Summit for prosecutors working on these important cases.”

Tony Reid, a private investigator who has been trying to get the PCJU to review one of his client’s cases for more than a year, questions why it has taken so long to establish protocols for the unit when there are plenty of other models to follow.

District attorneys in Los Angeles, San Francisco, and San Diego all have conviction review units. And the United States Attorney General’s Office also has a unit dedicated to exonerating people who are factually innocent.

“It's not as if this is so drastically complicated that they can’t replicate that template and start the critical work now,” Reid said during a September interview with L.A. TACO. “Or use some of the existing protocols and refine them.”

“They are not reinventing the wheel,” Reid added.

Reid believes the California Attorney General's Office is dragging their feet because “their role in all this is something of a conflict of interest.”

“They are the top prosecutor for the state of California,” Reid continued. “Every time there is an [appeal] that comes up, it’s the attorney general's office that is arguing for the prosecution.”

“In my view, their goal has been: we’re going to uphold a verdict, and once it’s final, we’re going to do everything we can to uphold that verdict,” Reid said.

A post-conviction justice unit is a “suicide pill” for a prosecutor, Reid says, because they have to acknowledge that there is corruption within the legal system.

“They acknowledge the problem and that they are aware of the problem… but they don't want to act on them because they don’t want their friends and colleagues to get in trouble,” he said.

I don’t know that they have that many lawyers and the small amount of lawyers they do have are tasked with creating this unit from nothing.”

Joseph Trigillio, Executive Director of the Loyola Project for the Innocent

Reid represents Paul Kovacich, a 75-year-old former Placer County sheriff’s deputy who was convicted of fatally shooting his wife, Janet Kovacich, and disposing of her body.

Janet was last seen alive on September 8, 1982. After sending her two children off to school and talking with a friend, she was never seen or heard from again.

The circumstances of her disappearance didn’t add up. No cars were missing from her house and after having surgery recently, she wasn’t in a condition to drive.

There were two signs that someone broke into Paul and Janet’s house: a broken window in the back of their residence and several bent window screens.

In 1995, more than a decade after she vanished, two people walking on the dry lake bottom of Rollins Lake near Colfax noticed something buried in the silt: a weathered, partial human skull.

After remaining a cold case for more than two decades, around 2005 Janet’s case was reopened. About a year later, Paul was arrested before authorities were even able to confirm that the skull was possibly Janet’s.

During Paul’s trial, prosecutors argued that the skull had a hole that was consistent with an entrance wound caused by a gunshot from a large caliber handgun, similar to the weapon that Paul was issued as a police officer. And a forensic anthropologist testified that an artifact that could have been pieces of a bullet showed up in an x-ray of the skull, but no fragments were ever found. The Placer County coroner and three other experts disagreed with their opinion.

In 2009, Paul was convicted of first-degree murder and sentenced to 27 years-to-life in state prison.

From day one, Paul has maintained that he did not murder Janet. He was convicted largely based on “circumstantial evidence” and the testimony of two forensic experts, Reid said. Reid strongly believes that based on new forensic standards, the experts “would not have been able to make conclusive decisions” about the hole or possible fragments of lead in the skull.

Reid pointed to a 1995 email that shows that investigators had long had doubts about the evidence. In the email, Patrick Willey, a Placer County forensic anthropologist who examined the skull said, “If the bet was $10 he would say” the hole in the skull was a gunshot. But “if the bet was $100 he would say he couldn’t be sure.”

Reid called Paul’s case “a quintessential junk science case.”

“There is a tremendous amount of new evidence,” he said, including exculpatory evidence related to an FBI agent assigned to the case, that Reid says was never given to the defense.

Reid and Paul’s defense attorneys have tried to collect missing evidence and other documents related to the case, but the Placer County D.A.’s Office has “done nothing,” Reid said.

“You can hold your hand out to the district attorney's office but they hold all of the power,” Reid said.

Reid and Paul’s attorneys believe that the person who is actually responsible for Janet’s killing is, Joseph DeAngelo, the “Original Night Stalker” (also known as the “Golden State Killer”), the former cop who committed at least 13 murders, 51 rapes, and 120 burglaries across California between 1974 and 1986.

Reid describes the connections between Paul and DeAngelo as “compelling and significant.”

Janet and DeAngelo’s wife attended the same highschool and both DeAngelo and Paul worked as law enforcement officers in the same county during the ‘70s; DeAngelo for the Auburn Police Department and Paul for the Placer County Sheriff’s Department.

In 1979, Sergeant Kovacich apprehended a suspect who reoffended after being released from jail following a “bad arrest” by Officer DeAngelo. Kovacich ended up getting a letter of commendation, according to a memorandum reviewed by L.A. TACO, while DeAngelo likely received a reprimand.

That same year, DeAngelo was fired from the Auburn Police Department after he was arrested for shoplifting a hammer and dog repellent. Three years later Paul and Janet’s dog was suspiciously killed about a month before Janet went missing.

DeAngelo was known for meticulously planning his crimes.

He broke into homes to empty bullets from firearms, unlock doors, and remove screens before returning to rape and kill his victims. He used intricate knots to bind his victims and was able to avoid manhunts, which led some investigators to suspect that he was a law enforcement officer or had military training.

Reid believes Paul’s case is “exactly the kind of case that the AG’s conviction [review] unit should look at” since Placer County doesn’t have a unit. And they seemingly have no interest in starting one, Reid said.

“We’ve met nothing but bad faith,” he said, referring to the Placer County D.A.’s office.

Litigating a sprawling case like Paul’s could take more than a decade through the appeals process, Reid believes. “This is why we need a state [conviction review unit].”

Joseph Trigilio, executive director of the Loyola Project for the Innocent, agrees that Paul Kovacich’s case is well suited for the attorney general to review.

“The biggest reason is the fact that the tiny county doesn’t have the resources,” Trigilio said during a November interview with L.A. TACO. “If you don’t have a CIU, it’s hard to have prosecutors look at their own cases and review them. Once they get a conviction they stand by it.”

Trigillio says he doesn’t know why it’s taken the attorney general so long to start reviewing cases. But he could see limited staffing being one of the main factors.

“I don’t know that they have that many lawyers and the small amount of lawyers they do have are tasked with creating this unit from nothing,” he said. After publishing, Trigilio clarified that his remarks were based purely on speculation.

“It's a little more complicated that just replicating what local prosecutors do,” Trigillio pointed out, since the unit will mainly be focusing on cases that were handled by prosecutors outside of their office. “It’s not exactly apples to apples. It’s easier if you’re looking at cases that you prosecuted.”

But there are still “best practices” that the attorney general's office can learn from other conviction review units, he said.

Although the AG’s unit will mostly focus on jurisdictions that do not have conviction review units, for defendants who were prosecuted by the L.A. County D.A.’s Office, the attorney general’s unit could provide an additional pathway for exoneration.

“I think there is space for that,” Trigillio said, especially for “cases where there might be some potential conflicts,” such as cases that involve prosecutorial or police misconduct.

Although Los Angeles has arguably one of the most progressive conviction review units in the country, under George Gascon the D.A.’s office struggled to keep up with the demand for cases to be reviewed, as reported by L.A. TACO.

Nearly four years after District Attorney George Gascon relaunched the Conviction Integrity Unit, there were more than 150 cases in different stages of review as of September, a spokesperson for the D.A. confirmed. Some defendants have waited years to find out if their sentences could be overturned.

As of late August, fourteen people had been exonerated under the Gascón administration, according to the spokesperson. And five people had been resentenced through the unit.

But now that Gascon has left office and Nathan Hochman has been sworn in, it’s unclear what changes, if any, will be made to the unit.

On the campaign trail, Hochman promised to reverse many of Gascon’s most polarizing directives, such as Gascon’s decision to not seek sentencing enhancements in cases where defendants are accused of being associated with gangs.

But when it comes to exoneration and resentencing, Hochman is, so far, taking a more measured approach.

Two months before the election, Hochman told L.A. TACO that “the Conviction Integrity Unit and Resentencing Unit are essential parts of the DA's Office and will be maintained.”

He added, however, that he “will consult with prosecutors in both units to determine what's working well and where improvements can be made.”

“The Conviction Integrity Unit (CIU) was created by Jackie Lacey and is an important part of the office,” Hochman said. “There is no greater injustice in the criminal justice system than the conviction and incarceration of an innocent person. If my prosecutors or other credible entities, such as defense attorneys or innocence organizations, present compelling evidence that someone is factually innocent, I will act decisively in collaboration with the court to overturn the conviction and seek the individual's immediate release.”

Trigilio said that he had one meeting with Hochman in which the D.A. expressed that he wanted to make the CIU “more efficient.”

“I'm very hopeful and confident that the new D.A. will make the current CIU more robust,” Trigilio he said.

After the recent local and national elections, Reid is less optimistic about Hochman maintaining the CIU. Hochman’s position on the Menendez brothers case is already raising red flags for people, like him, in the innocence community. “I think that's a perfect example of what we can expect.”

“That really leaves the state as being our one and only safeguard for a conviction review unit,” he said. “It’s more important than ever to keep the focus on Bonta’s promise of a statewide [unit].”