This article was originally published by L.A. Public Press, and is republished here with permission.

Last month, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) published a report that calls to consider designating toxic pollution from the former Exide battery recycling plant in Vernon a federally prioritized “Superfund” site for cleanup.

“Superfund” is the term used to describe a government tool created by Congress in the 1980s to pay for the long-term clean-up of hazardous waste. It’s a designation dishonorably awarded to industrial sites that are so polluted and difficult for state and local authorities to manage, they require the federal government to step in.

Now, the feds appear poised to award that distinction to the area around the former battery smelter. While Exide has long been synonymous with toxic lead dust, the EPA’s recommendation was rooted in groundwater contamination, also linked to the plant. Specifically a carcinogen the EPA says Exide also released, trichloroethylene (TCE).

Officials, community advocates and residents had hoped the federal government would also move to expand the residential cleanup beyond its current 1.7 mile radius from the plant, to include any more homes known to be contaminated with lead from Exide. Though the EPA found that the soil lead levels don’t meet specific Superfund criteria as they are too close to “background” thresholds, many still hope the EPA will alter course before its final determination.

If the EPA ultimately decides against placing soil-lead cleanup around Exide on the Superfund list, however, “that does not mean the state can renege on its obligation to clean our homes,” warned mark! Lopez, community organizer and special projects organizer for community advocacy East Yard Communities for Environmental Justice.

It’s the continuation of long simmering community concerns that existing efforts made by the State of California aren’t enough, now touching federal regulators, too.

“It’s crazy,” said Terry Cano, who lives in Boyle Heights, about a mile and a half from the former plant. “It doesn’t make any sense to declare it Superfund and still not clean the homes.”

Years of Lead Cleanup

Long before the EPA poked its nose into the Exide site, the cleanup in and around the former battery recycling plant in Vernon had already been a long, costly, and monumental undertaking. It carries the dubious distinction of being one of the biggest hazardous waste cleanups in the state’s history.

Despite the high-profile nature of the project, and the unusually large amount of public funds secured for it, the colossal project has been bedeviled with problems. This includes contracting irregularities, shifting goalposts impacting some of the region’s most vulnerable, and safety concerns for the workers.

Since the plant was shuttered for good in 2015, workers contracted by California’s Department of Toxic Substances Control (DTSC) have visited more than 5,200 properties with intentions to remove contaminated soil from residents’ yards. It has not always been successful, leading to community-based audits finding contaminated soil after remediation.

Hundreds more homes await remediation. There are large plots of non-residential land that haven’t been touched. Nor is cleanup at the site of the former battery smelter complete either.

Cleaning up toxic lead has already cost California $772 million, according to the DTSC. Existing funds for the residential cleanup will only cover the cost of soil remediation at a few hundred more homes.

In 2022, the daunting scale of the remaining cleanup prompted state regulators to ask the feds for help. That request, to place the cleanup of the plant and the surrounding communities on the federal EPA’s National Priority List (NPL), resulted in the report the EPA published in June.

How Much Land Needs to Be Cleaned?

Officially, the state is cleaning contaminated properties within a 1.7 mile radius from the plant. State and federal regulators currently have no public plans to widen the boundary.

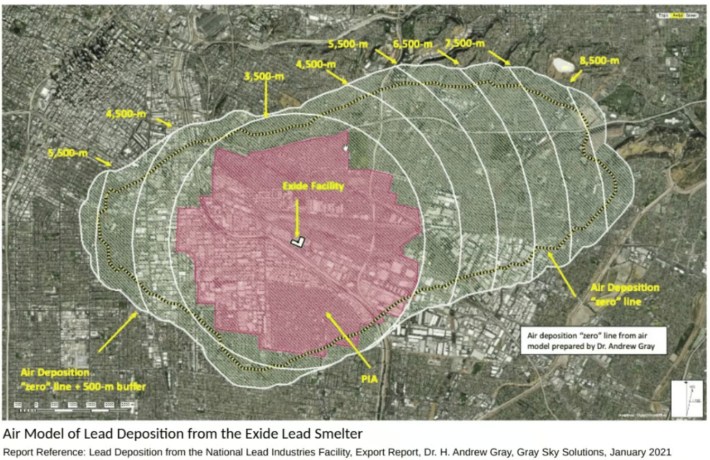

But nearly a decade into the project, various environmental experts, officials, community advocates and residents call for regulators to do just that. They say toxic air emissions from the facility, which started operating in the 1920s, could have extended out several miles from the plant.

LA County Supervisor Hilda Solis, whose district overlaps the cleanup area, wrote in a statement that she would “push” to expand the cleanup beyond the 1.7-mile radius to include homes “where there is evidence of soil and groundwater contamination.”

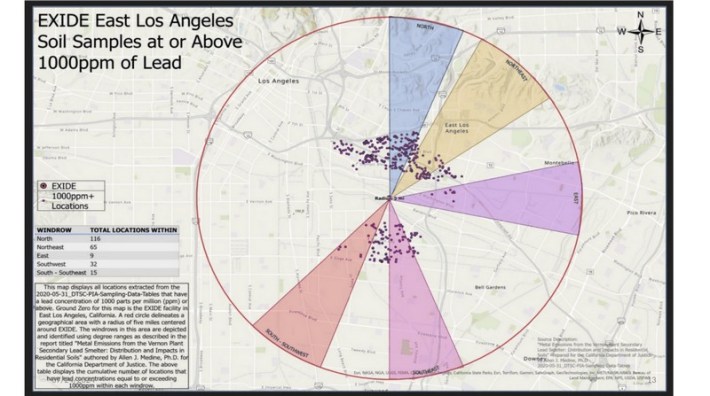

Last year, as part of a joint study between USC, East Yard Communities for Environmental Justice, and Occidental College, researchers conducted soil lead testing at 213 homes up to 4.5 miles from the plant. They found that about 40% of the homes tested had soil lead levels significantly higher than both state and federal cleanup thresholds. The mean amount of lead in the soil samples taken from beyond the 1.7 mile boundary was nearly 300 parts per million (ppm), the researchers found.

The DTSC has determined that the maximum acceptable soil lead levels for homes in the state is 80 ppm. The federal EPA, which typically has more permissive pollution regulations than many states, recommends a soil-lead cleanup threshold of 100 ppm in homes with multiple sources of the chemical, like paint and lead water service lines.

The findings prompted researchers to recommend the cleanup of contaminated homes to be extended within a 4.5-mile radius of the plant.

“We’re finding it at extremely alarming levels, so we should take action,” said Jill Johnston, associate professor of population and public health sciences at the USC Keck School of Medicine, about the soil lead levels beyond the 1.7-mile boundary. “The state should now be focused on protecting people’s health,” she added.

Indeed, “the state’s own evidence supports that there is contamination from Exide outside the 1.7 miles,” said Jane Williams, executive director of California Communities Against Toxics, an environmental advocacy organization.

Expand the Cleanup Zone?

A DTSC spokesperson wrote that some ten years ago the agency conducted sampling out to 4.5 miles from the former Exide facility. It determined that lead emissions from the plant may have contaminated soil up to 1.3 to 1.7 miles from the facility depending on wind direction.

“DTSC stands by the findings in the report provided to determine the [Preliminary Investigation Area] PIA,” wrote the DTSC spokesperson, using the acronym to describe the current cleanup zone.

That 2015 report, however, asserts that “additional data collection and analysis are needed to refine the estimated geographic boundary of facility emissions.”

Critics of the cleanup say that in the years since, the DTSC has done little such further analysis.

“If DTSC wants to refer to this report they should have reread it and got to work on the recommendations to gather more data, beyond the current boundaries,” said Lopez.

The EPA report does not make clear the extent of any testing the agency conducted beyond the 1.7 mile radius. However, the findings of a report by California Communities Against Toxics (CCAT)—using data put together by environmental science experts for the state’s ongoing legal battle to recover cleanup costs—suggest clear support for the calls to expand the cleanup around Exide.

Air pollution expert Dr. Andrew Gray, who has performed analysis of lead pollution around Exide for the state, estimates that air emissions could have deposited lead as far as five miles from the plant in areas where the wind direction is most prevalent. According to CCAT’s calculations, there could be thousands of additional homes needing remediation.

Their report found dozens of homes with some of the highest soil lead levels located at the outer limit of 1.7-mile current cleanup boundary. These are homes that had more than 1000 parts-per-million (ppm) of lead in the soil, according to state-originated data.

The California Communities Against Toxics report also uses state data to map children’s blood lead levels within a three-mile radius of the plant. The report found some of the highest percentages of children with blood-lead levels above the normal range close to the three-mile boundary from the former Exide plant.

Long-term exposures to lead are associated with an array of serious health issues including behavioral problems, learning difficulties, seizures, asthma and even death. Babies in the womb and young children are especially vulnerable to the neurotoxic effects from lead.

More Money Needed

Of the $772 million of state funding for the entire project, $573 million went for the residential cleanup, $132 million to cleanup activities at the facility, and $67 million for cleanup of the parkways, according to the DTSC.

If the remediation zone is widened, a key question will be who pays for it.

In 2020, Exide Technologies successfully filed for bankruptcy. The state’s ongoing cost recovery efforts against some of the other responsible parties hit a snarl earlier this year, when the judge ruled that the state had forwarded insufficient evidence to convince him that the lead beyond a quarter-mile from the plant is from Exide, according to Williams.

Representatives of Exide Technologies maintained the lead pollution in the communities around the plant could have also come from other sources like leaded gasoline and paint, and other lead-emitting industries in the area.

Indeed, the former Exide plant is in one of the most pollution-burdened parts of the state due to the cumulative impacts from poor air quality, proximity to hazardous waste threats and toxic cleanups, and ground and drinking water contamination.

There are scientific ways, however, of tracing the original source of lead pollution, including through “isotopic fingerprinting.” Critics of the cleanup say the state hasn’t taken the necessary steps to accurately determine the responsible parties.

“If you’re serious about cost recovery from the many owners of smelter in Los Angeles, you need to do the advanced environmental forensics, including the ‘fingerprinting’ of the lead, to prove that the lead came from the battery smelter and not from the cars or paint,” said Williams, critical of the state’s handling of cost recovery efforts. “They haven’t done that.”

The DTSC did not respond to questions about the steps the state has taken to accurately trace any lead pollution back to the former Exide plant.

According to Solis, more money, including federal funding, “is needed to ensure those impacted are recognized” in the ongoing cleanup.

“I was encouraged by the Environmental Protection Agency’s decision… to move Exide another step closer to Superfund eligibility and am grateful the State has asked them to move forward,” Solis added. “I urge the EPA to expedite their consideration and expand the cleanup zone to include all impacted properties.”