Aesthetically and practically speaking, John Dykstra is right about this place.

On the southeast periphery of the Van Nuys Airport, situated behind a chain-link fence adorned with barbed wire, is a two-story cinder block building that blends into this Valley industrial hub. From the inside, steel and wooden rafters support the roof of the nondescript, 12,000-square-foot warehouse at 6842 Valjean Avenue. (For you French literature and musical theatre fans, Valjean isn’t pronounced like the last name of the ex-convict-turned-benefactor protagonist of Les Misérables; it’s pronounced val-jeen.) There’s office space at the front of the building, on both floors.

“It’s a freakin’ warehouse,” says Dykstra, laughing. “See, that’s the thing that’s so weird about this. In and of itself it’s just a container; it didn’t even get photographed.” It’s a sentiment expressed a few times between my phone interview and initial email correspondence with the Oscar-winning visual effects supervisor. “It really didn’t have much personality,” he continues. “It was pretty much set up the way any kind of conventional warehouse, in that commercial environment, would be set up.”

However, in the (paraphrased) immortal words of Alec Guinness’s Obi-Wan Kenobi, there’s a cinematic energy field that surrounds and penetrates those who visit this storied location, and there’s reason to take pause.

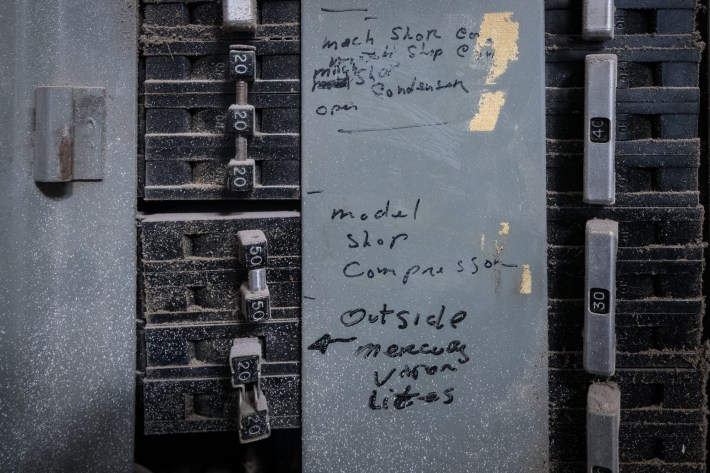

A breaker box just through the south rollup door has inscribed on it, in black permanent marker, the words “Model Shop.” Just outside of that door, the word APOGEE is written on the cement. And next to the front door, a brushed-metal plaque recognizes this building as the original home of George Lucas’s trailblazing visual company, Industrial Light & Magic (ILM).

This freakin’ warehouse is where a majority of the special photographic effects for Star Wars (1977) were created!

By the time Lucas made his groundbreaking space opera in the mid-1970s, American New Wave filmmakers—of which Lucas was a part—were making hard-hitting, socially conscious location-based films with a documentary edge, and effects departments within the movie studios had proven obsolete.

“They shut them down because they were making The French Connection and those kinds of movies,” says Richard Edlund, who is credited in Star Wars as first cameraman on the miniature and optical effects unit. Edlund and Dykstra, along with the late Grant McCune, Robert Blalack, and John Stears, won Oscars for the film’s innovative visual effects.

A studio had to be built from the ground up and Dykstra was hired for the gargantuan job of spearheading an independent effects company tasked with producing 360 effects shots for Lucas’s low-budget, sci-fi opus. (The film’s final budget was nearly $11.3 million – about $53.6 million today.)

According to the book The Making of Star Wars by J.W. Rinzler, Lucas had hoped to set up his effects shop in the Bay area, where he was based. However, Dykstra tells L.A. TACO that as far as he knows there was never a serious discussion about doing the work anywhere but L.A.

“Part of it was because we were still doing analog photography,” says Dykstra. “So, there were services and equipment and personnel that were available in Los Angeles that wouldn’t have been available in San Francisco, and this was a small budget movie. The idea of trying to gear up to do the work that we had planned for Star Wars, which was going to be a lot of invention, a lot of repurposing of existing technology, and we’re going to use film-based image capture, then we kind of wanted to be where all of that stuff was.”

Edlund says, “I think that there was a cadre of people in L.A. and the Valley that had the chops to do this kind of show and had the ability to learn how to do this show from scratch.”

Whatever building was chosen to house the budding effects company, it was imperative that it met a handful of criteria.

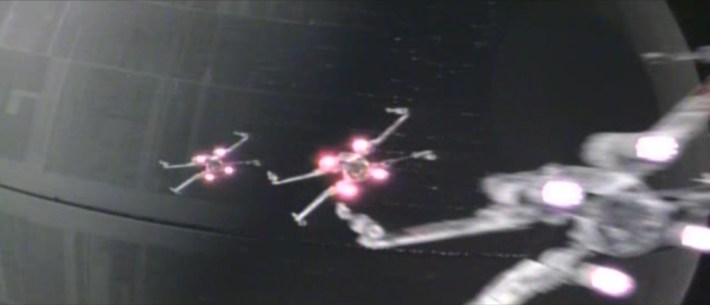

The flooring was of the utmost importance because Star Wars would require a new form of cinematography in order to depict space flight with a velocity and ferocity that was in contrast to the balletic spaceship maneuvers of 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) and other filmic depictions of space travel that came before it. Lucas famously spliced together a 16mm reel of aerial dogfights taken from old war films in order to illustrate the tone he was after for his head-to-head space battles.

“Prior to Star Wars, the only way you could do that kind of photography was using stop-motion [animation],” says Edlund. But the absence of motion within the individual frames created an unnatural stuttering effect. “If it didn’t blur, your ten-year-old viewer would say, ‘Hey, that looks funny,’ because it wouldn’t look real to him.”

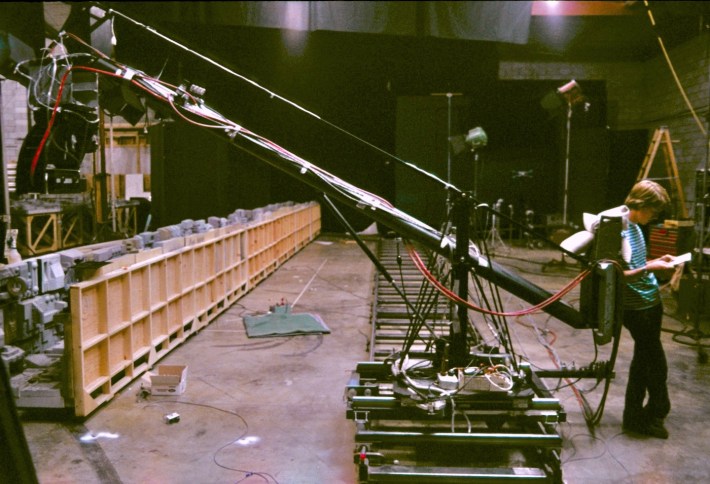

A motion control camera system, with which Dykstra had already been experimenting, was further developed and implemented on Star Wars. It was dubbed the Dykstraflex. By programming a computer to repeat a precise camera move over and over again, the filmmakers had the ability to accurately composite multiple elements and layers into a single, dynamic shot. It also produced the desired aesthetic of motion blur because the camera and models could move in real-time, making the shots appear as if a camera operator was actually filming ships flying through space.

“I wanted a cement floor because I had to do repeatable moves with precision [and] electromechanical positioning devices, and it doesn’t work if you’ve got the floor moving around with temperature and the flex that you get with wood,” says Dykstra.

The warehouse needed high ceilings for lighting purposes; a clear span of open floor space was required for the Dykstraflex and other photographic equipment, so a truss-style roof was essential.

Another significant consideration was the rent. Dykstra knew the studio couldn’t be centrally located in Hollywood because of high commercial real estate prices. Having worked in the Canoga Park facility of the late special effects wizard Douglas Trumbull, Dykstra was familiar with the Valley and knew there was affordable commercial property to be had. Having met his working criteria, and with a monthly rent of $2,300, Dykstra chose the warehouse on Valjean Avenue for the home of the fledgling Industrial Light & Magic. (The Industrial in the company’s name was derived from its location.) Dykstra purposely bought a house in Van Nuys at about the same time he started work on Star Wars. He was also a pilot who had flown gliders and was becoming interested in airplanes, so the studio’s proximity to the airport was an added benefit.

The company moved into the Valjean warehouse in the summer of 1975. During a six-week period, the space was converted to accommodate offices, two shooting stages, a model shop, a machine shop, a wood shop, a screening room, as well as optical, animation, editorial, and art departments. It took about nine months to build the camera and optical equipment.

Though no one knew what Star Wars was at the time, Dykstra considered the possibility of curious parties showing up uninvited. Dykstra explains that during his time assisting Trumbull on The Andromeda Strain (1971) and Silent Running (1972), hardcore film enthusiasts would mill about outside the shop. It seemed as though his mentor had gained a fan base because of his work in 2001. Dykstra didn’t want a repeat of that at ILM.

“One of the things that we wanted to do was not be harassed by people coming in and going through our garbage and all the kind of stuff that happened even back then,” says Dykstra. “One of the reasons it was called Industrial Light & Magic, when we came up with a name for it, was because we didn’t want to have it be a motion picture-themed name to avoid having people come and creep the parking lot.” A headline published on February 24, 1977, in the Valley News reads, “The Klingons have struck: 2 model spaceships filched”. The report, written three months before the release of Star Wars, uses Star Trek to make its point about two models “about the size of large watermelons” being stolen from ILM at 6842 Valjean Avenue. Dykstra has no specific recollection of the theft.

The location was also convenient to a variety of surplus stores, which provided quick solutions for acquiring parts that manufacturers may have taken months to turnaround. Edlund says they would send their driver to go find “some weird contraption” at Apex Surplus in Sun Valley or C&H Surplus in Pasadena. To a Star Wars fan, it may sound an awful lot like Luke Skywalker going to Tosche Station to pick up some power converters.

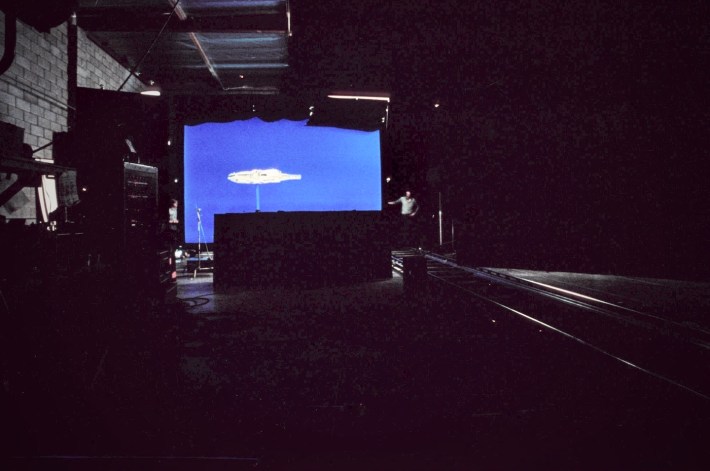

Photo courtesy of Dennis Muren.

Dennis Muren, the ILM legend whose Oscar-winning work on Terminator 2: Judgment Day (1991) and Jurassic Park (1993) helped to revolutionize the world of visual effects, says the Van Nuys studio had an “outlaw” vibe. “There were all different types of people,” says Muren, who mostly worked nights as the second cameraman while Edlund worked the day shift. Muren, like Edlund, had worked on commercials prior to Star Wars but also had some low-budget features under his belt. “There were very few people that had ever worked on a movie before,” says Muren. “I think we still had the spirit of the ‘60s, that you could sort of do something new and different and it was okay.”

“It was electric,” says Edlund of the working atmosphere at ILM. “The camaraderie that existed was partially because if we had a certain problem, and we didn’t quite know how to deal with that problem exactly ourselves, there would be somebody else you could lean on that would come in and help you figure it out.”

“Everybody kind of did everything, which was great. We were all people in our 20s and 30s,” says Dykstra. “It was a very collegial atmosphere. By the time we finished the movie it was very much a family, and that was one of the things that was unique about the work experience.” Dykstra calls the environment stressful but also relaxed. “I don’t mean relaxed in the sense that it’s lazy; I mean relaxed in the sense that rather than being bureaucratic it was more laissez-faire. I think we got a lot more done and I think it shows up in the work that’s in the movie, too, because people enjoyed working there.”

The operation ran 24 hours a day and the studio eventually got the nickname of the Country Club. The sweltering Valley heat, running equipment, hot lights, and no AC all contributed to temperatures rising well above a hundred degrees inside the studio. As such, staff would occasionally cool off in a hot tub of cold water in the parking lot. With a little bit of coconut oil applied, an escape slide from a Boeing 727 was transformed into a lunchtime water slide.

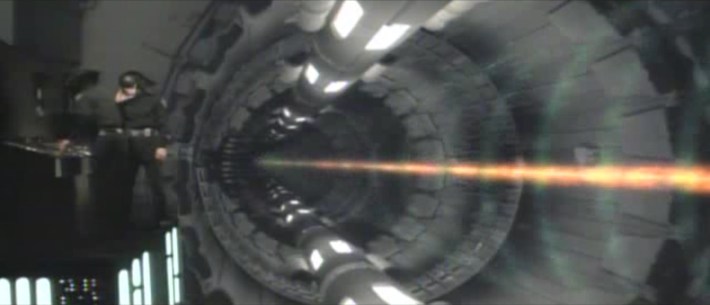

When it was time to work, however, water would eventually give way to fire in the parking lot. The surface of the Death Star was filmed with a camera hanging over the edge of a pickup truck going thirty miles per hour as pyrotechnics were set off. Inside the studio, Tie Fighters and Star Destroyers, X-Wings, and Y-Wings were brought to life. The infamous Death Star trench was about 60 feet in length and filmed with various forced perspective paintings at its far end to create more depth than what the space allowed in the miniature.

But the work produced in Van Nuys wasn’t limited to miniatures and models. Edlund shot the film’s iconic opening crawl, in five languages, at Valjean. The Death Star technicians firing the space station’s planet-destroying laser were filmed on a small set in front of a blue screen. That unpredictable seeker ball with which Luke trains while aboard the Millennium Falcon was made in the ILM model shop. Those irascible chess game creature holograms were filmed in a back corner of the warehouse using stop-motion animation.

After the effects for Star Wars were completed and the film opened on May 25, 1977, to massive success, ILM temporarily ceased operations, but Dykstra stayed at the location where he, Edlund and Muren worked on the effects for the Universal Television series Battlestar Galactica, employing the same equipment used on Star Wars. Edlund says they called the company MCA-57, after Universal’s parent company. “I think our phone number was 5757 or something like that,” he adds.

About a year later, Edlund rejoined ILM when the company relocated to San Rafael. Muren also made the move up North. Both OG ILMers worked on The Empire Strikes Back (1980) and Return of the Jedi (1983) and were awarded Special Achievement Oscars for visual effects for both sequels.

Dykstra formed a new company out of the Van Nuys studio called Apogee, Inc. He says it was “a partnership of basically all the people who were the department heads from ILM, with the exception of Dennis and Richard.” While running Apogee, Dykstra earned an Oscar nomination for Star Trek: The Motion Picture (1979). The company also produced the visual effects for Mel Brooks’ affectionate Star Wars send up, Spaceballs (1987). Apogee was also invested in other creative endeavors including commercial production, toy design, and the research and development of new visual effects equipment. It lasted about sixteen or seventeen years, says Dykstra, who later won the Oscar for visual effects for Spider-Man 2 (2004). More recently, he was the visual effects designer on Quentin Tarantino’s last four films.

Today, 6842 Valjean Avenue is the home of Neiman & Company, a custom architectural signage firm that’s been in business since 1965. They purchased and moved into the warehouse in 2002. Prior to that, a hospital supply company operated out of the space.

There was the fan that purchased at auction a piece of the Death Star surface that was filmed in the parking lot. Another fan, an architect from Canada, made arrangements months in advance to visit the building. A Japanese fan took precise measurements of the warehouse to create an animated 3D model of how the building appeared in the mid-'70s, when a ragtag group of filmmakers made moviegoers believe that a long time ago, in a galaxy far, far away, X-Wing fighters and an antiquated Corellian freighter called the Millennium Falcon could realistically face off against – and beat – an evil Empire and its decimating space station. They did so without the benefit of much time or money—a lot like the Rebel Alliance.

Reflecting back, Muren says that the Van Nuys ILM studio was “pretty neat.” He then stipulates, “I certainly in no way mean physically neat, and that was part of what was neat about it. It was kind of a mess. And it was organic and had been built up with deadlines and passion, and conflict and creativity.”

So, yeah, it’s a warehouse, but the Force is strong here.

Follow Jared on Twitter at @JaredCowan1.