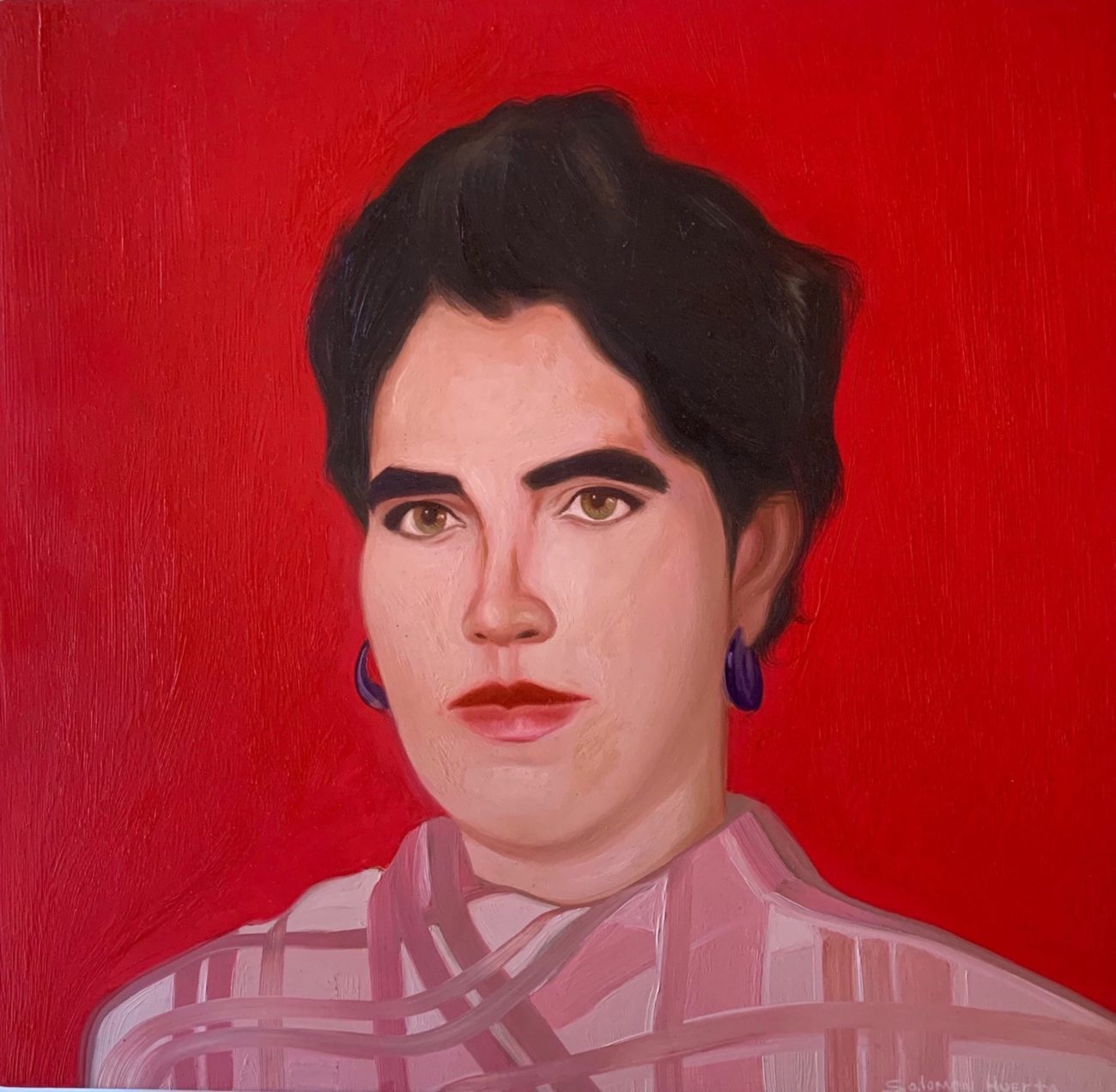

Welcome back to L.A. Taco’s column, “Barrio Wisdom.” In this series, we follow the streets-meet-academia wisdom of Dr. Álvaro Huerta, a professor at California State Polytechnic University, Pomona. In this installment, he writes an ode to his mother who after a life in El Norte, followed her dream to build her dream home in Tijuana.

[dropcap size=big]M[/dropcap]y late mother, Carmen Mejía Huerta, built her own home, brick by brick, in Mexico. Too poor to secure a piece of the “American Dream” in El Norte, during the mid-1980s, while residing in East Los Angeles, she decided to build her own home.

When she told my siblings and me—all eight of us—about her ambitious plans, we all thought she had gone mad.

“What are you going to do in Tijuana all by yourself?” I asked.

“No te preocupes demasiado,” she said. “Voy a construir un cuarto para cada uno de ustedes.”

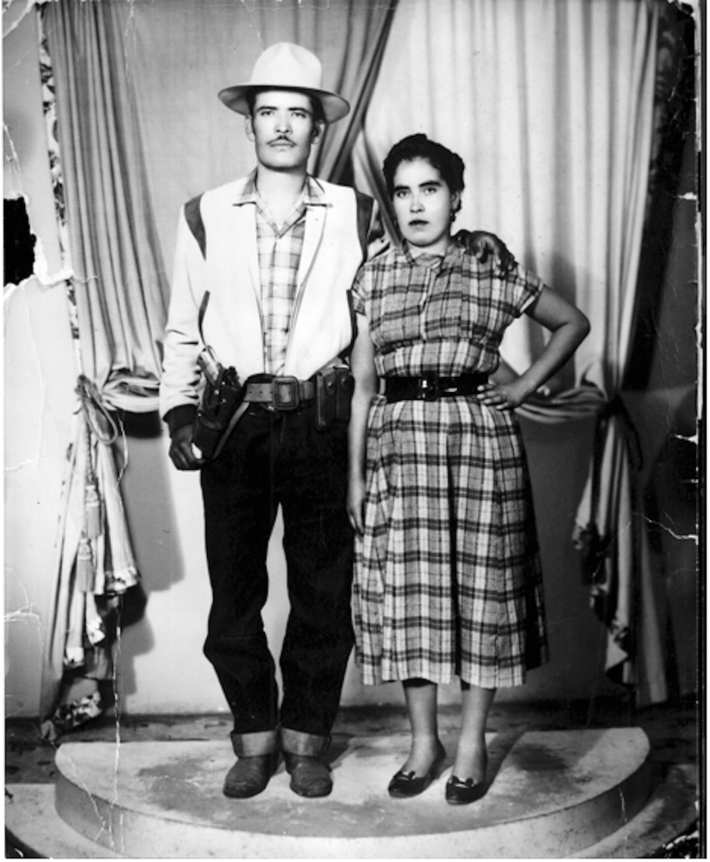

Our family, like many Mexican immigrants in this country, has a strong bond with Tijuana, Baja California—the border city where countless immigrants first settle before making their arduous journey to el norte. My Mexican parents first migrated to Tijuana from Zajo Grande, a rancho in Michoacán, during the early 1960s. They fled a bloody family feud that claimed the life of my paternal uncle Pascual.

As a so-called “good wife,” my mother relocated with my father (Salomón, Sr.) and his large family—parents and nine siblings—to Otay in la Colonia Libertad. Unlike the U.S., the poor in Latin America mostly live on the hillsides that circumscribe the outer reaches of urban areas, while the affluent reside in the city core.

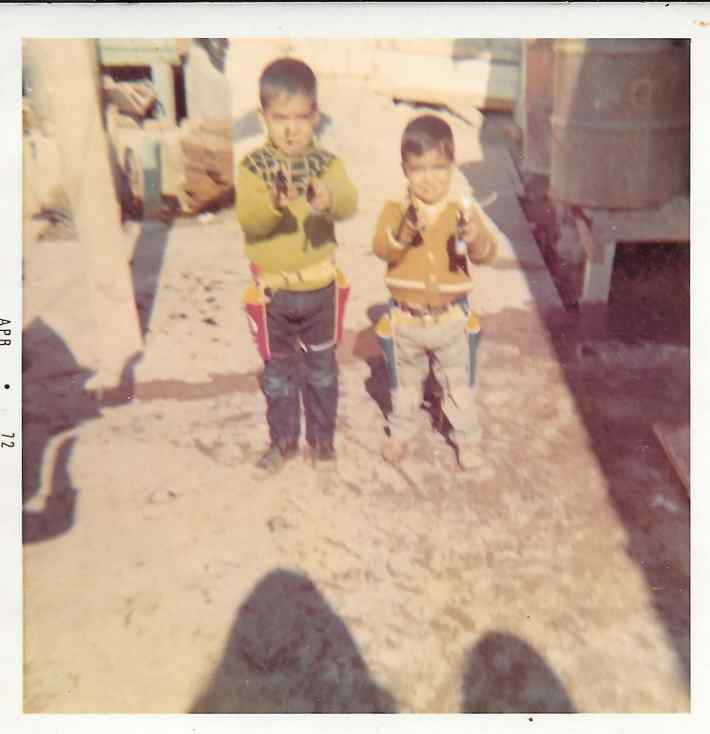

Once settled in Tijuana, she acquired an American work visa as a doméstica (domestic worker). While toiling for white, middle-class families in San Diego, California, she left us at home with our familia—immediate and extended. In her absence, my older sisters (Catalina, Soledad, and Ofelia) shared a role as surrogate “mothers,” cleaning, cooking, and caring for the younger kids (Salomón, Rosa and myself). They also began working outside our home in their teens, sacrificing their education—a common practice in developing and underdeveloped countries.

As a risk-taker, my mother, during her fifth pregnancy, arranged for me to be born in el norte. Accessing her kinship networks in the U.S., my mother delivered me in Sacramento, California. Isn’t San Diego closer to the border? Despite this conundrum, having a child born in the U.S. facilitated the process for my immediate family to successfully apply for micas (green cards) in this country.

Once in the U.S., my mother continued to labor tirelessly as a doméstica while my father was never paid more than the minimum wage of $3.25 per hour in a series of mostly dead-end jobs as a janitor and day laborer. With no formal education and a lack of English proficiency, compounded by limited occupational skills, my parents applied for government aid and public housing assistance, which led to a protracted tenancy at the notorious Ramona Gardens public housing project (or Big Hazard projects) in Boyle Heights—not far from the predominantly Latino communities of El Sereno, City Terrace, and Lincoln Heights.

Tired of the overcrowding, abject poverty, violence, drugs, gangs, police abuse, and bleak prospects that plagued the projects, my mother decided to return to the motherland, Mexico, as a refuge.

During my freshman year at UCLA, she called me to say that she purchased a small, empty lot in Tijuana to build her dream home. While initially shocked, thinking that she’d wasted her money, I requested an emergency student loan to support her dream. Given her unconditional love for me (and my siblings), I acted without hesitation. On the loan application, I wrote: “Help Mexican immigrant mother to escape the projects.”

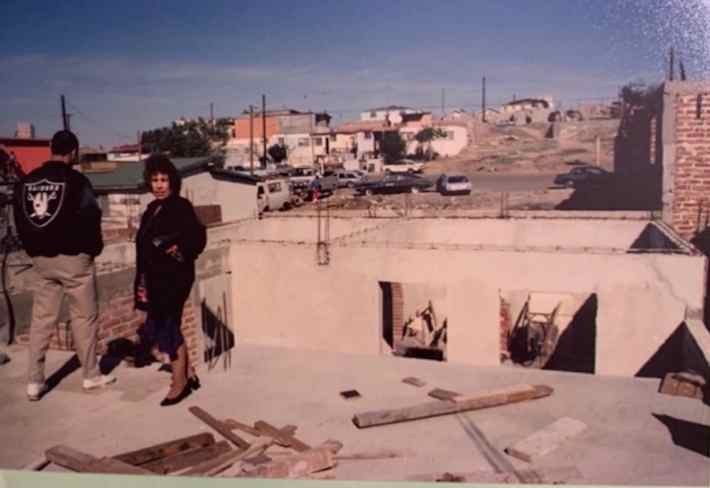

Several years after acquiring the lot, my mother gave my siblings and me a tour. Like a recent graduate of UC Berkeley’s architecture program, she presented her design plan and created a visual image for us of her finished home.

“Aquí es donde irá la cocina y la sala por ahí,” she said with confidence, as we surveyed the unfinished home. We listened with deep skepticism.

In retrospect, we never should’ve doubted her. This is the same woman who as a 13-year-old, hit a potential kidnapper in the head with a rock to escape. Had the menacing man, Alcadio, succeeded in abducting her for several days and returning her home, she would’ve been forced to marry him to “save her honor” or the “family’s honor,” a barbaric practice that continues to the present in many parts of the world. Fortunately for my siblings and I, at the tender age of 14, she married a handsome man named Salomón Chávez Huerta.

This is the same woman who worked as a doméstica in the U.S. for over 40 years to provide for her family. She’s the one who forced my father to take my older brother Salomón and I, as lazy teenagers, to work as day laborers in Malibu so we could learn to appreciate the importance of higher education.

“Si no los llevas al trabajo,” she threatened my father, as he watched Westerns on T.V., “entonces los llevaré.”

For many years, my mother—with the help of the family—slowly built her dream home. First came the cement foundation and then the walls. The roof followed. Then came the windows and doors. Not satisfied with one-story, she added a second level. My father included a guest house in the back. While she initially protested, she later appreciated having extra units to rent.

Defying the odds, she transformed an empty space with rocks, used tires, and broken glass into the most beautiful home on the block—probably in the entire colonia. She hired and fired workers, fixed leaky faucets and remodeled, (re)painted the walls, and changed the kitchen cabinets like there was no end.

Much of the family considered the Tijuana home our mother’s unhealthy obsession. Yet, for my mother, it represented a healthy passion later in life. The home was the product of a long journey for a Mexican immigrant who lacked formal education and could never secure upward mobility in El Norte. But at the end of the day, she wasn’t going to let anyone derail her Mexican dream.

For the first time in her life, in Tijuana, my mother cleaned and improved her own home, rather than those belonging to the privileged, white Americans she “served” for over forty years.

I only wish I could see her beautiful face and smile once more to tell how proud I am of her.