“We are not born rich, and we have a pride for something we like doing, and our mind just becomes creative to do different things,” says Julian Anguiano, owner of Mystyx Kafe. Street vendors line the sidewalks in Boyle Heights, providing locals with accessible and affordable meals every day. Their contribution to the community goes beyond what they sell and is based heavily on what they represent; cultural identity, union, and tradition.

The clock strikes four AM. Outside Boyle Heights, the sky is still dark. Hundreds of street vendors have made their way out of bed, preparing and setting up for what will be a long, busy day. Locals are greeted by the smell of freshly homemade tamales and champurrado. Across the street, another vendor has set up a coffee stand, the first of its kind. More and more street vendors arrive, each unique in their own right, providing only their best work in hopes of earning just enough to get by.

One of the hardest tasks when trying to capture the true essence of street vendors was the unfortunate realization that the pandemic had made street vendors become so scarce. With everyone in quarantine, street vendors lost clientele and saw themselves facing this new reality: they were forced to adapt to an environment where people no longer strolled in the park.

I must have gone to a dozen parks in the mighty quest of finding a street vendor that would sell me a raspado or esquite, but to my surprise, I stumbled upon empty and gloomy parks with almost no one in sight. Originally established at the pandemic's peak on the corner of Cesar Chavez Avenue and Rowan Avenue in front of Superior Grocers, street vendors had found the ideal place to be newly seen and acknowledged. What once might have been just another corner became the epicenter of possibilities within this community of street vendors and small businesses. With people only making trips out for essential needs, street vendors quickly understood that gathering around a grocery store would benefit their business and a broken community that had lost their freedom and ability to come together.

Below are the stories and experiences of six street vendors from Boyle Heights.

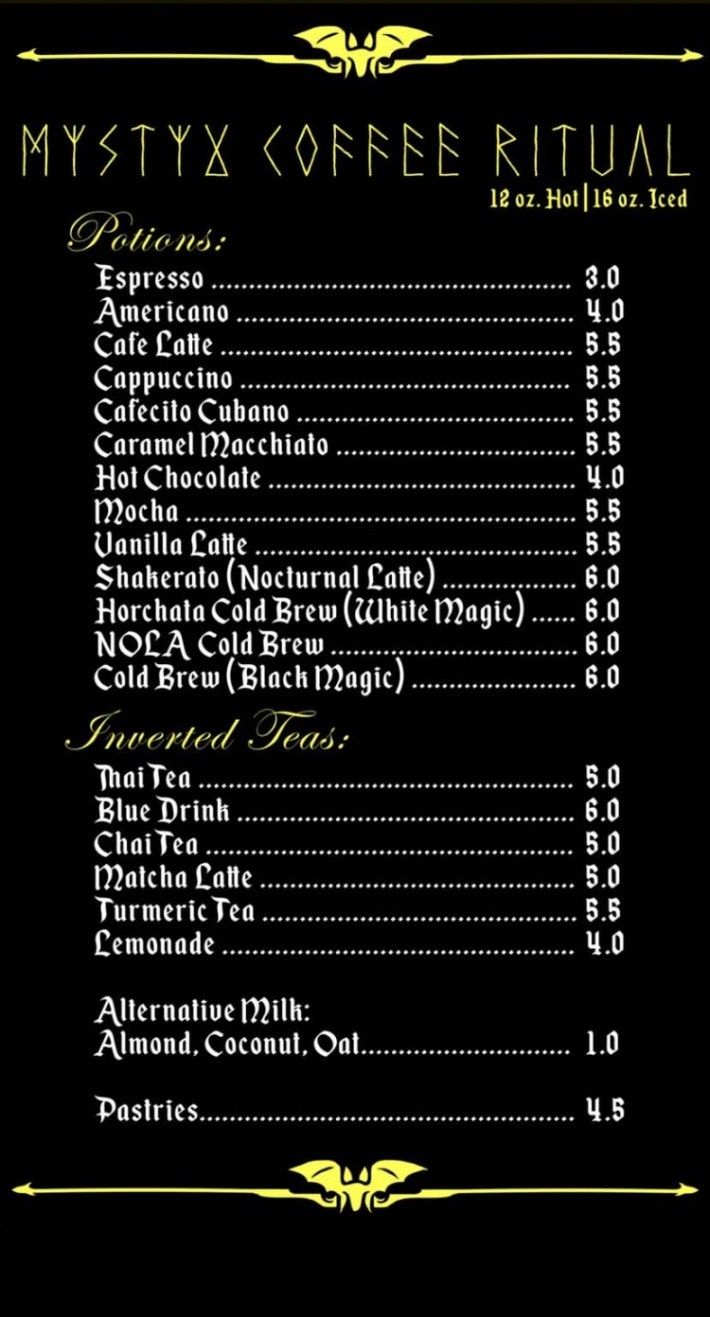

Julián Anguiano — The Man Behind Mystyx Kafe

Julián Anguiano, from East L.A., started his small business Mystyx Kafe about two and a half years ago on the corner of Cesar Chavez Avenue and Rowan Avenue

Having dreams of becoming a wrestler as a little kid, Anguiano didn’t originally plan to grow up and own his very own coffee shop. Through the years, he gained a passion for what he now does for a living.

“I have my espresso machine with my coffee cart, and this is what I love to do,” says Anguiano with a smile.

Mystyx Kafe started as a coffee stand and is now set to open its first brick mortar in the upcoming months on the corner of Cesar Chavez Avenue and Ford Blvd. in East LA.

Anguiano explains his love for gothic music and the inspiration it played in establishing his brand.

“I wanted to do something different; gothic music and coffee at the same time. I think we’ve accomplished that,” says Anguiano.

He takes pride in being consistent, which is something he has come to learn doesn’t always come quickly. There are days when he is overwhelmed and tired but still manages to show up in the name of his business and community.

He’s been fortunate to have the ongoing support of the locals and explains that despite the few incidents he’s had with the city regarding their permit, he has seen the better side of this job.

Running his own business has proven to be very time-consuming, as he finds himself working all of the time, but he reassures me, he loves his job.

Follow Mystyx Kafe at @mystyxkafe on Instagram.

From Hobby to Small Business — Maria’s Knitted Garments Line the Sidewalks

Maria runs a small business in the same corner of Cesar Chavez Ave. and Rowan Ave., selling garments she knits herself. She shows off her knitted collection, which includes a variety of hats with different themes and funky patterns, with some showcasing Pikachu and Minion designs.

Her latest work is Dodger-themed hats, which she is in the process of finishing after having a customer specifically ask her to make them.

Maria has only been selling on this corner for the past four weekends but explains she began selling outside a nearby school, and it was, unfortunately, due to the pandemic that she was unable to sell anymore.

She decided to try her luck one more time, explaining she understands this business is unreliable and consistency in earnings isn’t always a given.

“Hace ocho días no vendí nada, ayer ya vendí $10…ahora a ver que suerte me toca,” (“Eight days ago I didn’t sell anything, yesterday I sold $10… let’s see how lucky I get today,” states Maria).

She explains that she does knitting as a hobby whenever she has free time and doesn’t necessarily believe it contributes much to the community. It is, however, the labor and dedication, along with creativity, that makes her work unique and valuable.

Julia Ortiz Talks About Her Experience as a Florist for Nearly 15 Years

It is less than a mile away from that intersection that lies yet another busy street, with vibrant flowers and street vendors alike. Stationed in front of Indiana and 4th streets houses, street vendors line the sidewalk stretching their arms out unto the street for passing cars to stop and buy floral arrangements for their loved ones. Julia Ortiz, a Boyle Heights native, has dedicated the last 15 years of her life to the art of making bouquets on the corner near the exit of the 60 freeway. She takes pride in her work and has been able to learn more throughout the years to be able to provide for her community.

As a vendor, she has dealt with numerous people paying with counterfeit money and multiple incidents in which those in cars have asked for flowers and quickly sped away without paying.

Ortiz expresses this sadness in knowing that resorting to the police when things like these happen doesn’t have any effect. She urges those in power to create a system in which street vendors are valued, and the city feels responsible for implementing a security system they so desperately need.

“Nos ayudaran mas y nos pusieran mas patrullas para que vigilen a toda la gente que trabaja en la calle.” (“To help us more and have more patrols circulating the area taking care of all the people who work on the street,” urges Ortiz.)

This comes after multiple attacks on street vendors in recent years. Despite the coverage and acknowledgment of this problem, street vendors are still being left to fend for themselves, feeling as though they are alone with no one to turn to.

“Todos los que trabajamos en la calle, nos sentimos solos porque no tenemos ayuda del gobierno.”(“All of us who work on the street feel alone, because we don’t have help from the government,” states Ortiz.)

Susana Morales Fights for a Better System that Ensures the Safety of Street Vendors

Stationed at the corner of Soto and 1st streets, Susana Morales, a Boyle Heights native, runs a small business selling clothing and other basic essentials.

She originally began selling at a nearby corner on Cesar Chavez Avenue and Fickett Street many years ago. She was the first to arrive at a block that, while infested with trash, brought it back to life and began her small business. She takes pride in knowing that she has earned her stay by always cooperating with adjacent brick and businesses in maintaining a clean and welcoming space.

Throughout the many years, she has stumbled upon people who’ve tried to push her away, but she calmly points at a business card that she keeps on her phone as she explains she’s been given the right to sell by the local developers.

Morales was forced to move from her initial location to 1st st as she recounts the number of times she witnessed the heinous attacks on fellow vendor and friend Martina Lopez.

With the arrival of vendors from neighboring communities, competitiveness took over, and problems arose. Morales and other Boyle Heights vendors found themselves losing clientele at the hands of those who drove miles to displace them.

She narrates the occasion in which her friend was physically attacked by the son of a fellow street vendor. She describes another occasion in which she was personally attacked by this specific vendor, as well. While she was not physically harmed, she was publicly humiliated and threatened.

Despite the countless efforts for justice and police reports, Morales and Lopez haven’t achieved anything.

“Sean conscientes por favor. Porque a ella le hicieron algo y ustedes no quieren hacer nada?” (“Please be more conscious. Why did they do something to her, and you don’t want to do anything?” asked Morales in frustration.)

Morales continued by explaining the betrayal and disappointment she has endured at the ineptitude of various local politicians.

Having been promised a grant that would aid street vendors, Morales looked forward in anticipation, feeling, perhaps for the first time, the city cared for her work.

Upon months of hearing nothing, Morales remained hopeful that council member Kevin de León and assembly member Miguel Santiago would have some answers. It was to her surprise and utter disappointment that she learned said grants had been distributed, and she had not been lucky enough to have been provided with the aid. Morales was told that, given her inability to provide a working permit, she did not qualify for the grant. At this point, she took it upon herself and asked various street vendors that, unlike her, did have a permit, but just like her, they all shared the same sorrow in knowing that, once again, they had been forgotten.

Morales urges for justice and the needed coverage to tell her story, as well as that of one of her friends, who lives in the shadows under fear of possible retaliation.

“Yo te pido que la apoyes porque ella está sola.” ("I ask you to support her because she is alone,” states Morales.)

Margarita Vargas Mentions “Homelessness” As She Urges for More to Be Done

Margaritas Vargas is one of the four workers that help set up and run a taco stand called “Tacos San Juditas” on the same corner of Soto and 1st Streets every evening until late at night. This taco stand has been operating on this corner for about a year with two additional locations, including a catering service they provide.

Vargas takes pride in providing the best service possible and is always happy to hear how much the customers love the tacos. Prioritizing good service allows the customers to enjoy the experience and allows the workers to have a good day with a sense of accomplishment.

She has not had any bad experiences except for the usual customer who’s grown mad as they’ve waited “too long.” She explains the process of getting to the location, bringing everything down, and setting up and how this takes a while. Unfortunately, some customers don’t comprehend it and grow hungry, desperate and upset.

Vargas mentions the homelessness issue and how it harms the professionalism of those who work on the street. As she explained this, a local resident, who’s notoriously known for their erratic behavior, paced back and forth, yelling obscenities in front of their stand.

Vargas hopes the media wouldn’t focus so heavily on depicting street vendors as people who violate their permits and instead opt to show the struggles they face allowing the community to see where the problem truly lies.

Whether it’s the city throwing away all their merchandise or an individual constantly terrorizing them, Vargas asks for more coverage to find support and an established sense of security.

“Porque no mejor checar a la gente; a los indigentes, los que andan en la calle atacando, que uno que anda trabajando honestamente y simplemente ganándose un centavo dignamente,’’

(“Instead, why can’t they pay more attention to other people, the homeless, those who attack us on the street, than paying more attention to someone who is working honestly and simply earning a decent penny,” demands Vargas.)

Vargas explains her contribution to the community is through consumption which in return helps the economy. She works hard to provide the best customer service and hopes that it is something the community values and appreciates.

Follow Tacos San Juditas at @tacos_san_juditas on Instagram.

Voces Indígenas— Marcos Galicia Upholds Mexican Tradition Through His Work

Marcos Galicia has been selling at Mariachi Plaza for nearly 16 years. He runs a small business called Voces Indígenas, where he displays a collection of Mexican handcrafts and folk art made initially in Mexican states within indigenous communities.

He runs a nonprofit organization called Voces Indígenas, dedicated to preserving indigenous music, specifically from the pre-Columbian era, such as the one that originates from clay flutes.

Through this ideology, he’s been able to conserve the Mexican tradition and uphold it through his work and make a living out of it. He shared having very positive experiences. Perhaps the only struggle he’s faced is feeling as though his work is unappreciated. Still, he is happy to see the community is moving towards a more conscious understanding and acceptance of the labor involved.

“Tendemos a no valorar o pedir descuentos…Se trabaja casi todo el tiempo porque a veces es una persona que corre todo…es bastante trabajo; el que compra, el que ordena, el que limpia, el que acomoda…cuando pedimos un descuento…no vemos el trabajo que hay detrás.” (We are used to not appreciating and asking for discounts, but we work almost all of the time because sometimes there is only one person who runs everything… It’s a lot of work; the one who buys, the one who orders, the one who cleans, the one who sets up… when we ask for a discount… we don’t see the work that goes on in the back,” states Galicia.)

He takes pride in providing this sense of nostalgia and closeness to home through the Mexican folk art and handcrafts he sells. Despite differing belief systems, Galicia explains that folk art can unite people as it represents cultural identity and love for one’s roots.

“La artesanía representa completamente a México. Independientemente de cual sea nuestra cosmovisión de religión nos recordamos mucho con este tipo de cosas.”(“Folk artfully represents Mexico. Regardless of our religious views, we remember our roots a lot with this kind of thing,” states Galicia.)

He explains that becoming an independent entrepreneur as a Latino involves being very conscious and purpose-driven. He explains that there is no actual competition, based solely on the focus and dedication you put into the work that will give you results and allow you to grow.

“Si se concentra uno en la idea y el propósito que tiene como vendedor o persona siempre va a ver una forma que va a salir adelante porque estamos completamente seguro de lo uno está haciendo.”

(“If you focus on the idea and the purpose you have as a seller or person, you will always find a path that will be successful, because you are completely sure of what you are doing,” advises Galicia.)

Follow Voces Indígenas at @voces_indígenas on Instagram.

Street vendors have always been a symbol of work ethic and resilience. Through their work and service, we can come together and share an extraordinary sense of community and unity worth more than any products they sell.

As the community pillars that they are, there is a responsibility to which we must hold the city up and demand better conditions and regulations that will ensure every street vendor is accounted for and never forgotten.

Street vendors can’t and won’t be simplified into one more attack under an “unstable” job because they are way more than that.

Among the many things they represent are culture, tradition, and identity.

They are the pride of Boyle Heights.