[dropcap size=big]R[/dropcap] aised in the City Terrace section of East Los Angeles, the award-winning poet and educator Sesshu Foster is one of the most influential Angeleno authors of the last 30 years. Throughout a career dating to the mid-1980s, he has taught English in East Los Angeles public schools. His new book from Kaya Press, City of the Future, continues his legacy of mapping the real Los Angeles and resisting the “apartheid imagination” through writing, poetry, and the mentorship of new generations.

The new book is nearly 200 pages, divided into 10 sections, and combines poetry and prose. Foster’s writing bends genres such as documentary and poetry with surrealism, the elegiac with urban studies. His hybrid poetics reflect his own mixed heritage. Born to a Japanese-American mother and Caucasian father, Foster is often assumed to be Chicano or is considered by many to be an honorary Chicano, because he’s spent so many years in the Latin arts community and lived almost all his life in East Los Angeles.

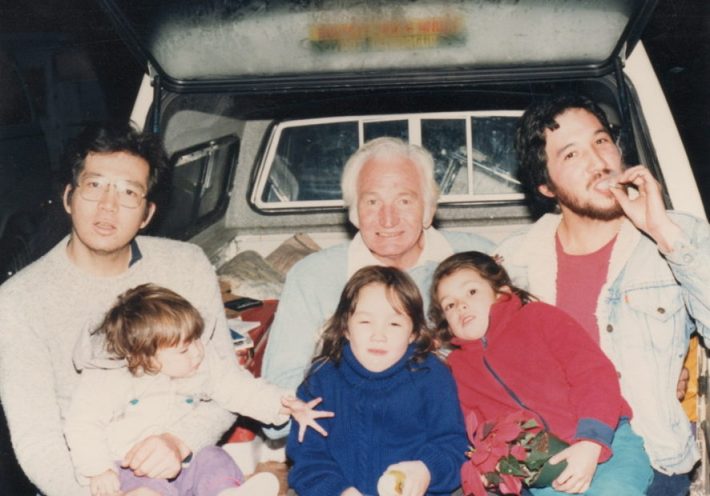

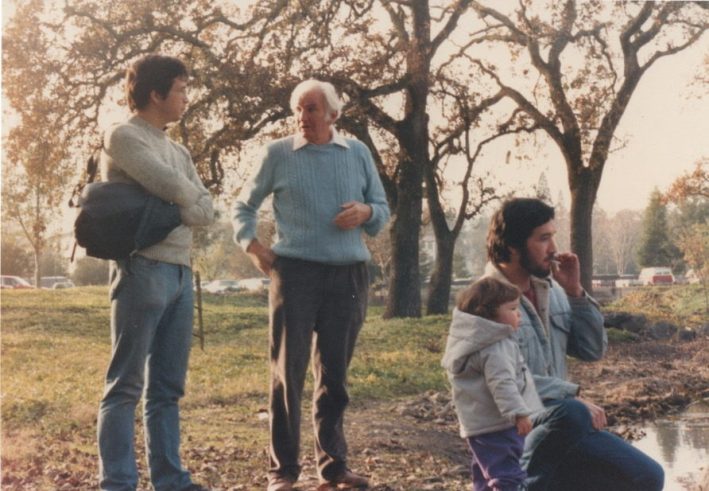

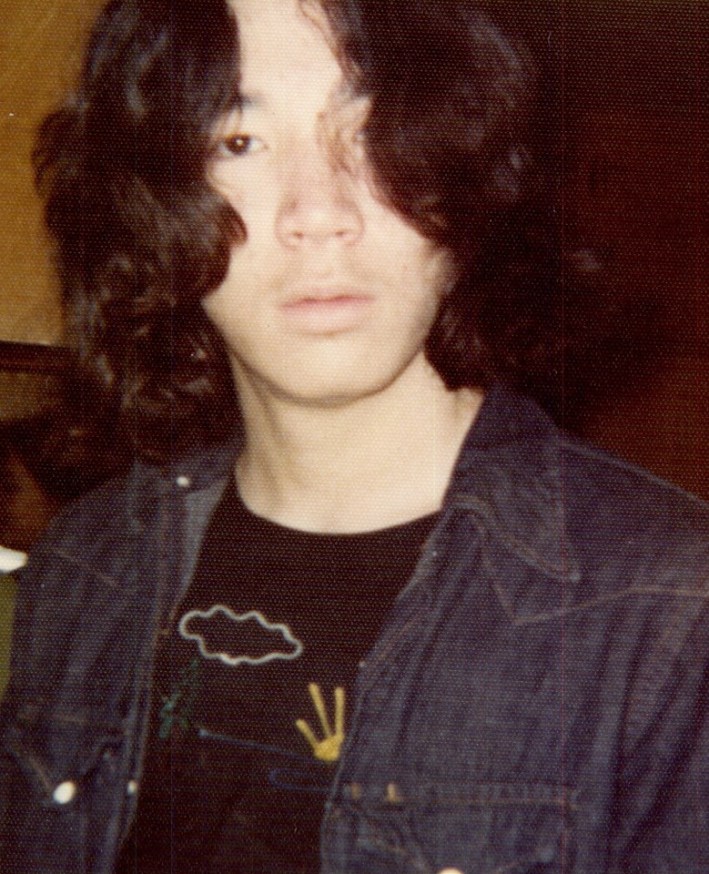

Foster, left, with family in the 80s. Courtesy of Sesshu Foster.

The pieces in the new book are: “Postcards written with ocotillo and yucca. Gentrification of your face inside your sleep. Privatization of identity, corners, and intimations. Wars on the nerve, colors, breathing.” Dozens of the pieces are only a page, while several extend up to nine or ten pages. There are postcards, list poems, segmented essays, and many that defy category. In some cases, he’s critiquing racism and gentrification directly, others are subtle and sarcastic, and then there are thoughtful elegies paying tribute to his recently deceased father and brother, departed close friends, and his late literary role models like Wanda Coleman. The book’s title can be interpreted several ways, but one of the main reasons is that Foster proposes values and ethics that are needed for longevity and creating a “City of the Future.”

After ‘landing’ these ‘middle class’ writers or artists live the detached life of tourists, who want a life served to them by community.

One of the best examples is one of the final pieces in City of the Future, a segmented essay titled, “How is the Artist or Writer to Function (Survive and Produce) in the Community Outside of Institutions.” Originally published on his blog and then republished by the Poetry Foundation, this pithy essay offers advice and practical wisdom from Foster’s lifetime of writing, teaching, parenting and above all, living. The piece not only offers core values and ethics, it also critiques “parachute journalists,” who drop into communities to extract what they want, but then fail to give back.

Foster writes: “After ‘landing’ these ‘middle class’ writers or artists live the detached life of tourists, who want a life served to them by community. They want no part of the struggle to make the community.” In many ways, City of the Future is a manifesto on why persisting through the struggle is ultimately worth it if artistic integrity and building community are values you believe in. Foster’s lifework is a testimony to this.

Postcards from the Heart

[dropcap size=big]N[/dropcap] amed after a 15th Century Zen artist, his parents were both creatives steeped in the ethos of the Beat Generation. They split up early in his youth and he was raised by his mother. Foster is a graduate of Wilson High School in El Sereno followed by UC Santa Cruz for his Bachelors, Cal State L.A. for his Teaching Credential and then the Iowa Writers Workshop for his MFA in the 1990s. Married for 37 years, with three adult daughters, Foster is a pillar of his community.

He was first published while in high school around 1973-1974 in Gidra, the underground publication of the Japanese-American community in the late 1960s-early 1970s. The piece was called “Imagine,” and it was a riff on the John Lennon song. Foster explains how it happened: “I heard about Gidra from two friends, James Lew and Wallace Wong, who worked at the Little Tokyo Service Center. Wally learned that after I filled my notebooks with drawings and poems, I simply threw them away. He took a stack of them to Gidra and that's how I was first published.”

(For more on Gidra and the Radical Asian-American Movement of the late 1960s-early 1970s, see Karen Ishizuka’s fascinating 2016 book on Verso, Serve the People.)

Foster, left, with family in the 80s. Courtesy of Sesshu Foster.

Foster credits the period he grew up in as the source of his writing voice. “The spirit of the time, for me, was dire and conflicted,” he recalls. “When I was in kindergarten, the teacher announced JFK had been assassinated and started crying, in front of a class of five-year-olds. I moved to City Terrace in 1965, when the city was rocked by the Watts riots. The Vietnam War was on TV every night, and they expected us to register for the draft, to go kill or be killed. The contempt of the U.S. government for Asian lives was as clear and distinct as their proudest pronouncements on the firebombing of Tokyo or the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. American attitudes toward killing people of color were the same as killing Indians a century before.”

“While I was in middle school, MLK, Malcolm X, and other Civil Rights leaders were assassinated, RFK was assassinated at the Ambassador Hotel, and people were killed in our neighborhood frequently in what was called ‘drug-related’ or ‘gang-related’ violence,” he continues. Riffs on a number of the topics mentioned above appear in his breakout book, 1996’s City Terrace Field Manual, also from Kaya Press. That collection covered his rite of passage in City Terrace, his teenage years and his first years as a teacher and parent. Foster’s work follows a hybrid format in more ways than one.

‘I met Allen Ginsberg in the elevator.’

An ideal example of this is a prose poem in the new book called, “South Pasadena Postcard.” In the space of a paragraph, he writes a heartbreaking arc about running into his daughter’s former best friend at the bank. “Neither of us mentioned the event that changed their lives,” he writes, “and set in motion the events that separated her from my daughter, her mom’s death in an SUV rollover in Texas. She said she wished to get in touch with my daughter and I assured her that I would relay the message. ‘It’s great to see you,’ I said. I didn’t say that her mom had been a wonderful person, full of sweetness and laughter. I didn’t tell her now that she colored her hair, she’d given herself her mom’s color.” This type of pathos runs through City of the Future.

Courtesy of Kaya Press.

Foster also co-edited a groundbreaking anthology of Los Angeles Poetry in 1989, Invocation L.A. Published by West End Press, it won the American Book Award in 1990. The subtitle of the collection is “Urban Multicultural Poetry” and it is considered the first truly multicultural LA Poetry anthology. After winning the award, the Before Columbus Foundation flew Foster and co-editors Naomi Quinones and Michelle T. Clinton to the Miami Book Fair to receive the award.

“It was our first American Book Award and it was a big deal,” Foster says. “The book won West End Press publisher John Crawford a Literary Achievement award,” Foster recalls. “I met Allen Ginsberg in the elevator, and as we headed to the punch bowl, he asked us, ‘What's your favorite first line from a poem?’ He congratulated John Crawford on winning and kissed the top of John's bald head.” Another memorable moment on the trip was meeting “Quincy Troupe, who removed his dentures and said he lost his four top front teeth in jail in the South during the Civil Rights Movement.”

Deconstructing the Apartheid Imagination

[dropcap size=big]I[/dropcap] first met Foster in 2009, at a local poetry event. In addition to hearing him read many times, I have interviewed him twice and had dozens of conversations both in person and online. In 2015, he drove me around City Terrace for three hours and showed me murals I never knew existed like Willie Herron’s “The Wall That Cracked Open,” in a City Terrace alley and Paul Botello’s piece “Inner Resources,” at City Terrace Park. He also drove me to his childhood home on the northeastern side of City Terrace where I met his now 92-year-old mother. She’s been in the same City Terrace home for 53 years. Our most recent interview took place at La Monarca Bakery in South Pasadena on a warm late winter afternoon.

Foster is an encyclopedia of Los Angeles history with countless personal anecdotes about the years he grew up. “My father was shot at an LAUSD job site in 1969,” he explains. “He then spent a year on his back in a cast that went from his ankles to his chest. There were students shot on the front steps of my high school and I knew friends shot at or shot in the neighborhood. I myself did not expect to live long, even though I refused to register for the draft. It was a desperate time, that's the way it felt for me. At the same time, the curious thing was, everyone knew things were changing. There was hope things were going to get better, which seems very different from nowadays. Nowadays people seem to distract themselves from hard facts with every gadget and app they can get.”

This hybrid of hard facts, reality and hope pervades his work and is employed to deconstruct the violent hierarchy and shed light on some oversight. One of the most powerful pieces in his new book is “The Apartheid Imagination.” The prose poem rails against the apartheid imagination, which he describes as “the perfect spell, the perfect killing tool, the killing machine.”

Furthermore, he adds, “the apartheid imagination requires no location, no physical body; because it has laws, records, court buildings, cells, conversations and life.” The piece culminates with him denouncing the apartheid imagination because “they were happy to see half my family two generations dispossessed and sent to live in horse stalls of Santa Anita racetrack and Colorado river internment camps, happy to go along with lives being destroyed, happy to sign some apology letters decades later, put up a few plaques on historical sites out in the desert.” In one of the final lines of the piece he writes, “I place this line in front of it saying my whole life has been against it, and the rest of my life will be against it.”

RELATED: Profile of a Modern-Day Poet in L.A.

Foster sees his vocation as an English teacher as his vehicle to subvert the apartheid imagination. Teaching is a major source of his political and spiritual fulfillment. He is fulfilled by nurturing his student’s writing and critical thinking skills. When asked about how he has managed to write so much in between raising three daughters, maintaining a happy marriage, and teaching English for 30 years, Foster told me that he “believes in the public space in the public sector for the public good.” He does not see it as a chore even when he reads 200 pages of student work every week. “It’s worth it to me,” Foster confesses, “because I am living my values.”

Courtesy of Kaya Press.

Documentary Poetics

[dropcap size=big]J[/dropcap] ust about every June once school is out, he goes camping for a week to recharge his batteries. His love of the great outdoors and camping is why he also spent several summers in his 20s and 30s working in logging and fighting fires in the Rockies. In his first book, 1987’s Angry Days, he writes about the several summers he worked in this capacity. These experiences are why he also likes Gary Snyder’s poetry documenting mountains, logging and fighting fires.

The last piece in Angry Days is titled “A Note on Form,” and this short essay is integral to understanding his poetics. Foster writes: “In terms of a poetic tradition, what workers say in lunchrooms or over coffee first thing in the morning may not be formally recognized as such, but I grew up with it, with what people say over a cold beer on the porch. I operate with it, I relate to it, like most of us do, working our way through. I hope my work is some tribute to those who struggle on.”

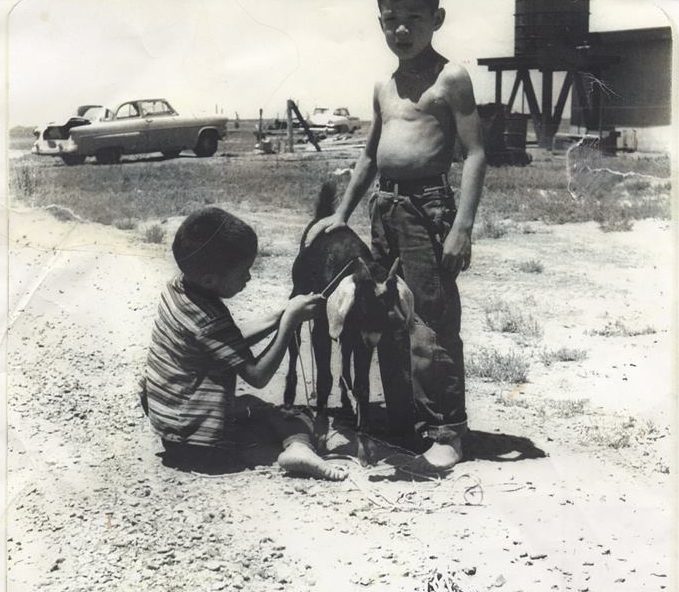

A young Foster, right, with a goat in Los Baños. Courtesy of Sesshu Foster.

The second section of the new book is titled “City of the Future,” and this 21-page section is an extended collage of recounted moments, surrealist musings, snippets of conversation, and pithy aphorism-like observations that carry on Foster’s inclination toward celebrating the everyday quotidian with a laser-like focus. This attention to detail is a sort of documentary poetics.

The Nicaraguan poet Ernesto Cardenal influenced Foster with his book Zero Hour and Other Documentary Poems. Cardenal inspired Foster, he says, “by the catholic (with a lower c) way he integrated Ezra Pound's historical mytho-poetics with his own Nicaraguan Exteriorism, poems dedicated to the anti-Somoza struggle and against the Imperialist economics of underdevelopment.”

Another piece in City of the Future that really adheres to Documentary Poetics is “Walking East Manifesto.” The ten-page piece is a hybrid prose poem that uses questions, aphorisms about walking, a list of statistics about how many people were killed as pedestrians from 1976 to 2010 and satire to extol the virtues of walking. Switching registers and tones swiftly through the piece, it’s an exhilarating tour de force. He asks many questions like: “Does the person on your driver’s license look like a ghost?” And did, “Your car turn you into someone you don’t even like? Happened?” He reminds the reader that, “Walking passes everything through a new angle. Walking is the sourness which opens its vista on that terrain which has been made consecrated forgotten in our language in our brain in our habits.” Foster uses the techniques of documentary poetry to illuminate and entertain with the same veracity as Ernesto Cardenal.

Courtesy of Kaya Press.

Holding Space in the Community

[dropcap size=big]O[/dropcap] ne of Foster’s most memorable periods of teaching was running an afterschool poetry club at Hollenbeck Middle School with Ruben Martinez in the late 1980s. Their poetry club was called “Poets Beyond Madness.” Despite Foster's busy schedule with his family, teaching, and labor organizing, the rewards of the club were so gratifying that they met several times a week.

Foster explains that “Poetry frees students up. Schools always talk about skills, but poetry builds imagination. I saw those kids put transformation into action and it started with poetry.” One of his students from that era, Karla Diaz wrote a letter to an organization in Spain and her writing was so compelling that she ended up being flown out there after they read her letter and she was in the 8th grade.

Diaz is now a successful writer and Los Angeles artist. She remembers Foster fondly. “Sesshu Foster was my junior high school English teacher,” she recently told me. “As a young writer and student, he gave me invaluable skills not only in my writing, but also in my personal growth.” English was not Diaz’s first language and before studying with Foster, she had a hard time in her ESL Classes and hated English/writing classes because they “read stories that had nothing to do with my personal experiences,” she says. He showed her books that were closer to home.

“These books I could tell had been given to him and were signed by the authors,” she states. “And they were such rare books—the ones you never see in libraries. I felt so special. I loved them! Those books became my library. I read and read. While my friends in the neighborhood were playing basketball or joining a gang, I read Sesshu’s books. They were my teachers.”

‘This land was not a magically unpeopled wilderness to be colonized but a place of history, secrets, struggles.’

“One day,” Diaz recalls, “I went to see him read at LACMA and he called me from the audience to share my poetry. Writing was an outlet for me. It was an alternative space to create. I grew up in a low-income single family with my mother and two siblings. Money was always low in our household and I knew my mother didn’t have the money to pay for writing classes for me or buy me books.” This was years before there were any bookstores in Boyle Heights.

His kindness and generosity left an indelible impression on her. “Thinking back to all of this, he didn’t have to do any of it,” she says. “There were many teachers who ignored us and labeled us as dumb. For his friendship and guidance, I will be eternally grateful. I will always be thankful to him for being a visionary—for seeing something worthy and valuable in me that no one else saw.”

RELATED: How Shihan Van Clief Made His Mark on HBO's Def Poetry Jam

Another similar anecdote occurred in Mexico City at the International Airport when Foster was there for a literary festival. Amid making his way through the busy airport, he ran into one of his first poetry students from Boyle Heights. At the time, Foster was in a cast on crutches because he had just broken his ankle hiking in the Cascade Mountains. He was hobbling through the airport with his luggage and barely making it, when he saw his former student Paula Gonzalez.

Gonzalez is now a TV producer at Telemundo in Miami. She greeted him warmly and helped him through the airport. They connected there for a moment and she told him that even though she does not write poetry like she did back in his class, the powers of imagination she developed studying with him serve her career in Miami as a broadcast journalist.

A Transformative Activity

[dropcap size=big]A[/dropcap] s noted earlier, one of the most important pieces in City of the Future is, “How is the Artist or Writer to Function (Survive and Produce) in the Community Outside of Institutions.” Some of the statements are straightforward such as how he worked two jobs for two decades to support his writing habit, another example is when he says: “meet the people in your community. Talk to the elders. Find out how they have used intelligence and creativity to survive as human beings.”

Foster in the 70s. Courtesy of Sesshu Foster.

The piece culminates with a sentiment that Foster has lived. “You, young artist, young writer,” he expresses. “Go anywhere you like. But know that a community was there before you — this land was not a magically unpeopled wilderness to be colonized but a place of history, secrets, struggles, heroes and issues. What made it community was not magic, but labor. Maybe if your labor and work relates to them, if your aesthetic process is open to that community, your work will not be superfluous. Your work might be useful.”

A few sentences later he concludes: “This argues against the artist or writer as tourist, as parachute journalist. You can develop more organic sources.” Furthermore, he adds, “Your own aesthetic process is a transformative activity; it’s not an economic transaction that you purchase with a university degree.”

Foster is understated, but slow and steady. His consistent work and the substance behind it is why E. Tammy Kim wrote in Al-Jazeera in 2015 that “As gentrification sweeps the city, Sesshu Foster has quietly become the poet laureate of a vanishing neighborhood.” In City of the Future, Foster continues his tradition of nurturing the next generation, honoring his community, and shining a light in the hidden corners.