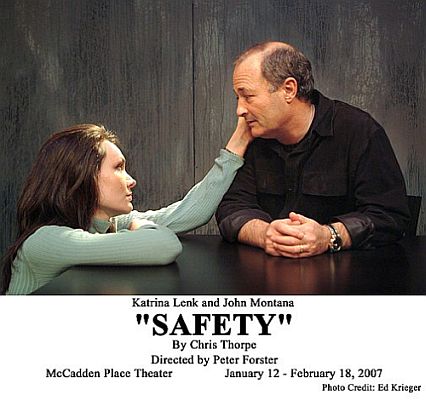

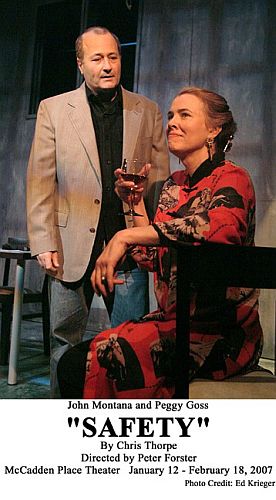

(Photos: Ed Krieger)

(Photos: Ed Krieger)

Safety @ The McCadden Theatre ~1157 N. McCadden Place Hollywood,CA 90038~Through Februay 18, Thursdays-Saturdays ~ 8:00 ~ Sundays @2:00 ~ $15.00-$20.00

"The breath of death is the most deadly when the dead revisits in your dreams, stays much longer than the final moments you shared with them, and brings much meaner and nastier visions every year." Dennis Kyne, Gulf War Veteran, in "SUPPORT THE TRUTH."

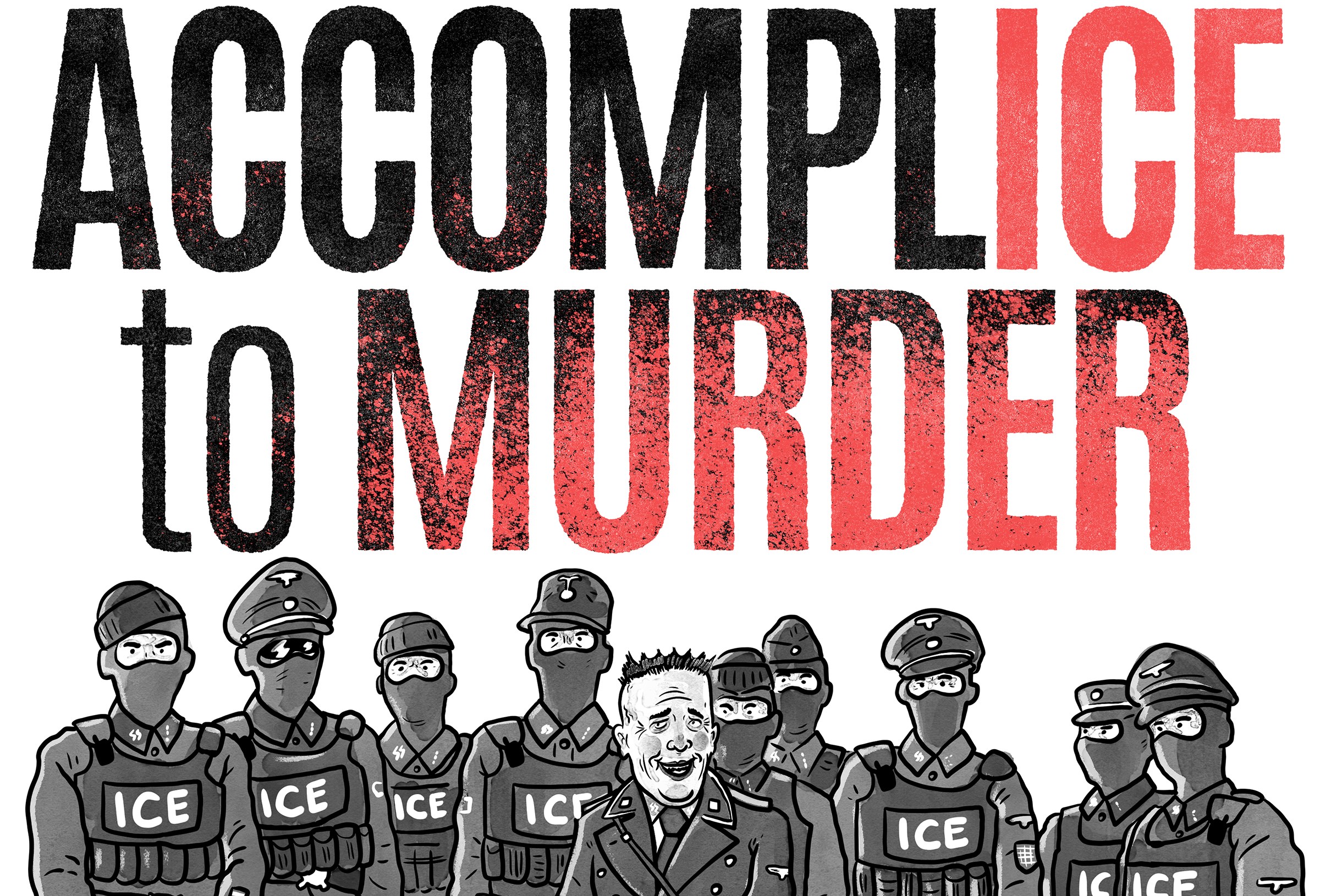

Michael is not God; he doesn't kill, but he shoots, his dead victims then served to us the next morning over breakfast, the blood of his subjects, like our cups of coffee, still steaming on the front page of the newspaper...that is, IF his hand wasn't shaking from dodging bullets and the lighting and composition were just right. In SAFETY, written by British playwright Chris Thorpe, Michael (John Montana), a war photographer, finds himself feeling as exposed as his graphic subjects - mostly dying boy-soldiers - when a retrospective of his work and an almost fatal family accident combine to make headlines.

"Are you deeply affected?" presses Tanya, a young, ambitious journalist (Katrina Lenk) who sees beauty in Michael's depictions of carnage, and searches for the same polish in his heart. "Did you see her?" is the more disturbing inquiry of his embittered wife (Peggy Goss), teetering on the abyss of a nervous breakdown, as to whether her husband, back for some R&R, saw his daugther drown before Sean (Mac Brandt), a simple man who did the right thing, saved the 12-year old girl's life.

Michael, just like a young, idealistic soldier, first went into battle under the illusion he was doing the right thing, in his case documenting the horrors of war in the hopes of stopping them. But the trauma of witnessing death first-hand and living in combat zones year after year took their toll on him. After a while, every battlefield resembles the next and each mission undertaken becomes "just a job." Rest-stops back home mirror those of returning combat vets, struggling to reintegrate the normalcy of civilian life with extreme experience. Michael feels closer to the dead and the dying he photographed than to his own survivor daughter. "The dying see everything you ever did." To survive and work on the battlefield, Michael clings to the euthanizing of his deeper feelings, no doubt the root of the criticism he receives at home for not being a nurturing husband and father.

SAFETY transports us from our relatively cozy lives in a peaceful, democratic society where reality is most closely measured by our willingness to turn on the TV, or open the Firefox icon or the papers to read about the war - and drops us onto the battlefield where Michael candidly confides to us the horrific truths lurking behind his most celebrated pictures. Bearing witness to a damaged life at home or the battleground of Michael's mind are not necessarily easier. A self-professed "barely human" being who flees a sarcastic wife and a nice suburban house every day to seek solace in London's lifeless hotel rooms with the mini bar as a best friend and the occasional company of a young woman to whom he guarantees "fantastic" sex in exchange for not saying a word.

Chris Thorpe wrote SAFETY in 2002, a year before the invasion of Iraq. It is haunting how much four years changes our relationship with the media. Sean is deemed "ignorant" by the elitist Michael for not reading the papers. In the internet age, 'uninformed' is what we call people who stick to major news outlets that resemble advertising circulars and government propaganda as their only source of information. It's also worth noting that the pressing issues on a journalist's mind in Iraq might be less about ethics and more about how to stay alive, one of many similarities to the soldiers whose lives they attempt to document. Sadly, the Iraq war plants another grim headstone with the greatest death toll among media personnel since World War II.

This heart-wrenching drama centers on an artist and father questioning if he is a monster who has sold his soul for a few good pictures. One could argue it might not be representitive of the average war photographer's life, feelings, or experience, but it makes for a compelling drama that still runs clearly with deep wellsprings of truth. After all, the nature of this work is to witness unbearable cruelty, suffering, and sadness and report it without interfering on any side. SAFETY gives a new meaning to the word 'sacrifice' when it comes to the unlucky souls sent to a war's front lines.

The play also makes a strong impression for its relevance and timing, with the script's best flippant remarks cast by a neglected wife, and every line played by a very sensitive and dynamic cast. It is the kind of artistic work that connects the house emotionally to the present Iraq invasion, just in the way pictures of dying American soldiers brought the Vietnam war home, helping stop it at a time before people were numb to images of death and violence and the government allowed access to them.