This article was produced by Capital & Main, an award-winning publication that reports from California on economic, political, and social issues. L.A. TACO is co-publishing this article.

By Jessica Goodheart

[dropcap size=big]J[/dropcap]orge Tejeda stands in his kitchen wearing blue jeans and a Dodgers cap explaining to reporters why he is waiting for sheriff’s deputies to arrive and evict him, his mother and four younger brothers. “We’ve been up and down with the rent,” he says. “Sometimes food is more important.” He is shy, soft spoken and only 26.

For the past few months, Tejeda, who operates a pallet jack at a food warehouse in downtown Los Angeles, has been the family’s sole source of income. He makes $16 an hour and works full time. His stepfather, a handyman named Jose Angel Silva, used to help out with the rent. But in December, he collapsed in a storeroom and spent months in the hospital with a serious case of COVID-19.

Then in April, Tejeda’s mother’s health deteriorated. A street vendor who sold tacos, aguas frescas and other wares, Maria Martinez, 44, is diabetic and can no longer ply her trade. Martinez understands that her eldest is under enormous pressure. “He’s the only one working right now,” she says in Spanish on the phone several days later, after her daily dialysis appointment. “Imagine if he lost his job and we didn’t have any income — I think we’d be even worse off.”

California’s eviction moratorium ended on Sept. 30. But tenants still have many protections now that they can be evicted in most of the state for failing to pay rent. The federal government has allocated $5.2 billion in funds for emergency assistance for California renters who have been impacted by the pandemic. That should be enough to retire the state’s rent debt, according to one analysis. Furthermore, a state law forbids landlords from moving forward with eviction proceedings based on nonpayment of rent between Oct. 1 and March 31, 2022, if the tenant has a rent relief application under review. Renters in the city of Los Angeles — like Martinez — have even greater protections than their counterparts elsewhere in the state. In fact, Los Angeles renters still cannot be evicted for nonpayment of rent if they have been impacted by the pandemic.

The state-wide eviction moratorium did not prevent Maria Martinez’s landlord from moving to eject her from the Tokio Hotel, a 49-unit boarding house in downtown L.A.

But advocates say all those supports, while helpful, don’t amount to much for those who don’t know about them or can’t navigate a confusing tangle of laws. The vulnerability of tenants like Martinez has fueled a nationwide movement to require legal representation for low income tenants facing eviction, just as criminal defendants are given attorneys as a matter of right. The pandemic has strengthened policymakers’ interest in staving off evictions. Fifteen cities and states have adopted “right to counsel” laws for those facing eviction, including New York City, San Francisco, Seattle and the states of Washington, Connecticut and Maryland. Seven of those laws have been adopted since the beginning of the pandemic, according to John Pollock, coordinator of the National Coalition for a Civil Right to Counsel.

Evictions have persisted during the pandemic, with Los Angeles County accounting for more than one-third of California’s 7,677 enforced lockouts between July 2020 and March 2021, according to CalMatters. Indeed, the state-wide eviction moratorium did not prevent Maria Martinez’s landlord from moving to eject her from the Tokio Hotel, a 49-unit downtown boarding house situated on a gritty corridor of wholesalers and discount electronics stores. Eviction proceedings began against her and at least two other tenants in the building prior to the expiration of the statewide eviction moratorium. Martinez speaks only Spanish, so she couldn’t read the court summons given to her in English. When her son figured out they were being evicted, he started packing up all of their belongings.

“In all the time I’ve lived here since I came from Mexico, I never imagined we would be in this situation,” Martinez says. At a food bank her family frequents, she connected with tenant advocates who helped her fill out an application for rental assistance. But her family’s lockout had already been scheduled for anytime on or after Oct. 2.

* * *

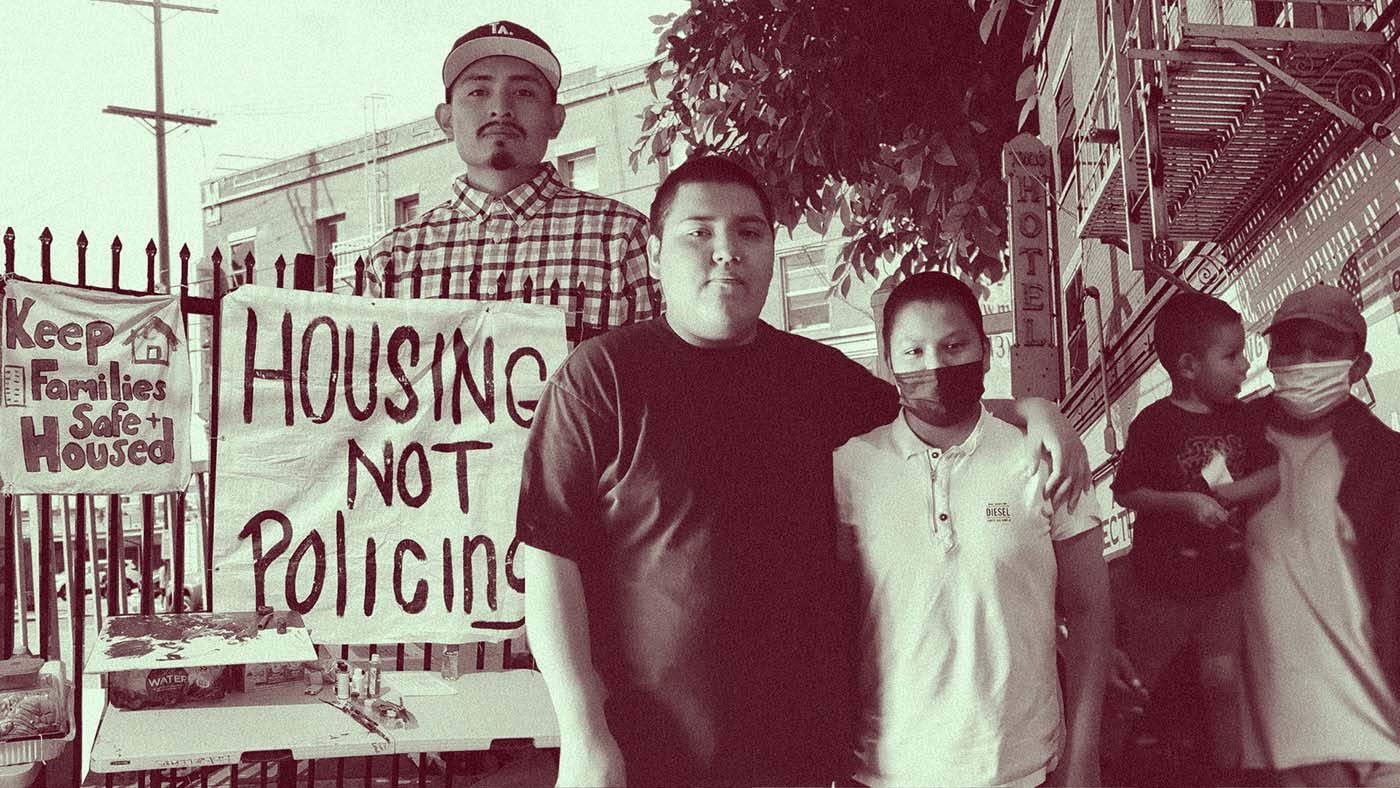

Outside the Tokio Hotel, a group of activists gather on Monday, Oct. 4, ready to form what they call a “blockade against eviction.” Their signs, mounted on a wrought iron fence, read, “Tenants Are Workers” and “Keep Families Safe and Housed.” Tejeda’s 3-year-old brother, Jose, painted an expressionist Batman, blissfully unaware of his family’s precarious housing situation.

This kind of direct action is what’s needed when an eviction is already underway, Pamela Agustin-Anguiano, coalition manager of Eastside LEADS, a community organization based in Boyle Heights, explains later. “It was a quick response,” she says. Three Eastside groups came together on short notice: Community Power Collective, Fideicomiso Comunitario Tierra Libre and her own organization. They had only learned the family was in peril several days before. Some of those who gathered were ready to risk arrest to keep the Martinez family in their home.

That proved unnecessary: A legal intervention staved off the lockout. And by the next day, a judge, perhaps persuaded by Martinez’s argument that she never received notice of the lawsuit, had issued a stay of the notice to vacate, keeping the Martinez family from being evicted, at least until the end of the month. On Oct. 25, a judge will determine whether the court will set aside its default judgment and allow Martinez to litigate her case. If the judge sides with the landlord, a sheriff’s deputy may be at her door and the family faces homelessness.

“Even if the landlord had a terrible reason for evicting, and would usually lose their case, a lot of them are still succeeding because tenants aren’t responding to the lawsuit in time.” ~ Charles Ross, attorney with Public Counsel

Two other tenants in the building are also facing possible eviction, including Tejeda’s uncle, Jose Efran Silva. And landlords are moving forward with eviction cases across L.A. County, hoping that tenants will not respond in time to court summonses, says Charles Ross, an attorney with Public Counsel representing Martinez.

“Right now, it doesn’t matter, even if the landlord had a terrible reason for evicting, and would usually lose their case, a lot of them are still succeeding because tenants aren’t responding to the lawsuit in time,” Ross says.

A family trust owns the building where the Martinez family has lived for the past 19 years. Viren Patel, who brought the eviction cases against Martinez and Silva, refused to comment for this story.

Ross and other advocates think broader access to attorneys, education and rental assistance will help tenants stay in their homes and ultimately save taxpayers money for such expenses as emergency shelter, housing and foster care. They would like to see the city and Los Angeles County follow the lead of New York City and other jurisdictions and adopt a right to counsel law.

“The right to counsel is the law that makes all other tenants rights real,” says Kaitlyn Quackenbush, assistant director of policy and research at Strategic Actions for a Just Economy (SAJE).

A Los Angeles coalition has been pushing for an ordinance since 2018, when Los Angeles City Councilman Paul Koretz introduced a motion to draft such a law. It was opposed by the Apartment Association of Greater Los Angeles, which continues to see it as an imposition on landlords who have suffered a loss of rental income during the pandemic.

“It’s the government’s balance sheet fighting against these small owners, many of whom are in tough financial positions themselves. Especially now after many [have] not receiv[ed] rent for more than 18 months,” says Daniel M. Yukelson, executive director of AAGLA. “There’s plenty of legal rights organizations, tenant rights organizations that provide legal counsel in eviction matters already for free,” he adds.

The rent at the Tokio Hotel is about $800 a month for one room, a tiny kitchen, a shared bathroom down the hall and, according to Maria Martinez, a recurrent bed bug and cockroach infestation.

More help has become available to renters since the right-to-counsel organizers launched their campaign. Last year the pandemic inspired the creation of Stay Housed LA, a network of community organizers and legal aid attorneys working to stave off evictions. It receives funding from Los Angeles County and the cities of Los Angeles, Long Beach and Santa Monica. But Quackenbush says that now’s the time for city and county officials to make a more substantial and enduring commitment to the region’s tenants. A fully implemented program in unincorporated Los Angeles County, home to about 74,000 low income renters, would cost $10 million per year, she estimates — representing a very small percentage of the overall county budget. She did not have an estimate for the cost of such a program in the city of Los Angeles, which is home to seven times as many low income tenants as unincorporated Los Angeles County.

Such investment in eviction prevention has yielded results in New York, which launched its program by focusing resources on zip codes with high rates of eviction. In 2019, residential evictions there declined by more than 40% compared to 2013. The percentage of tenants represented during that period also shot up from 1% to 38%. (Landlords typically have legal representation in an eviction case.) The toll of evictions on tenants is steep and can include damaged credit and disruption of work. Eviction and housing instability is especially hard on children, and can lead to emotional stress and behavioral problems.

* * *

In early October, while he awaited the sheriff’s deputies, Jorge Tejeda imagined finding a nicer place to live — one without a sink and ceiling that repeatedly leaked — and in a neighborhood that would provide a safer environment for his younger brothers. “This wasn’t the best area to grow up,” he says. Residents filed at least three health and safety complaints with the Los Angeles Housing Department against the Tokio Hotel in 2018 and 2019.

But Tejeda admits that he hadn’t had time to look and didn’t know what the family could afford. “I’m going to have to dig into that,” he says. The rent at the Tokio Hotel is about $800 a month for one room, a tiny kitchen, a shared bathroom down the hall and, according to his mother, a recurrent bed bug and cockroach infestation that has caused the family to discard mattresses and sofas, a costly expense that the landlord refused to bear. In Los Angeles County, fewer than 1% of apartments rent for less than $1,000 per month, according to Apartment List.

Still, Tejeda says he knows that for all its faults, the Tokio Hotel is the only home that his younger brothers have ever known. “They need to have school right nearby,” he says. Josh, who is 12, sits in the next room eating sandwiches around a square table with his brother, Henry, 18, both of whom stayed home from school because of the scheduled lockout. Josh says he likes to gaze out their second-floor window, which looks out on Central Avenue, and see the city light up at night. All Tejeda knows for sure is that he’s ready to take on extra shifts at the warehouse to make his family more secure. “If I could work all seven days I would,” he says.

Copyright 2021 Capital & Main

Angelika Albaladejo contributed to this story