A former Catholic priest in heavily brown SoCal parishes who was listed among alleged child abusers in 2004 has turned up a remote port city in Peru.

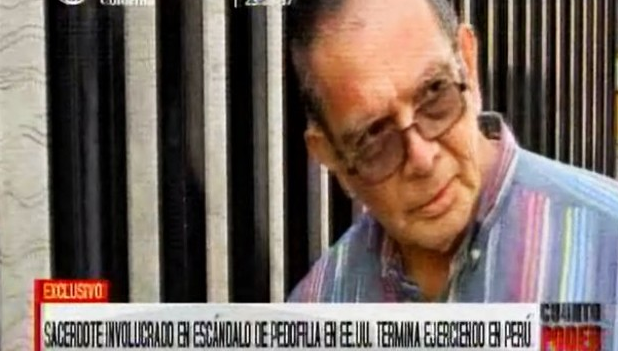

The former priest, Horacio Edgardo Arrunátegui Jimenez, appears in a Peruvian television magazine investigation that aired last month confirming that the long-hiding priest was happily posted in Chimbote, on Peru’s northern coast, serving as a hospital chaplain under the auspices of the local diocese.

Jimenez has been moving around between assignments in his native Peru and in Spain since he was abruptly removed from the ministry in Orange County. He was a popular priest in the late 1980s and early 1990s at the largely Latino parishes of St. Mary in Fullerton and St. Anthony Claret in Anaheim (yes, in Orange County).

And then he disappeared.

Diocesan officials told shocked parishioners back then that Jimenez had left on a missionary assignment, but they finally revealed the truth in 2004, in a press release that revealed all Orange County priests removed from ministry after “credible allegations” of child sexual abuse.

Those names were submitted to the John Jay College of Criminal Justice as part of the school’s pioneering 2004 study into the Catholic Church pedophile priest scandal. Jimenez was the only priest named who was not part of a $100 million settlement the Orange diocese reached with over 90 victims in 2005 — at that time, the largest settlement in the history of the American Catholic Church.

Now, Cuarto Poder — something like the 60 Minutes of Peru — has tracked down Jimenez to Chimbote. The report revealed that Jimenez had bounced around the world after Orange County by using different iterations of his full name. Horacio Jiménez in one country, Edgardo Arrunategui in another, and so forth. At one point in the report, a Cuarto Poder correspondent catches up with Jimenez as he is entering his home — accompanied by what the narrator drolly described as “an underage youth.”

“Talk to the bishop,” an angry Jimenez tells the reporter, adding:“There’s nothing to declare.”

And why do I care about some long-ago priest? Because I know the truth.

The story caused a scandal in Peru, as the local and national press rushed to interview an angry Angel Francisco Simon Piorno, the Chimbote bishop. The prelate claimed that he contacted the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB) to see if Jimenez was on their list of accused priests, and that they said Jimenez wasn’t— so to the bishop, that meant the investigative piece was false.

Simon went on to blame the scandal on money-hungry lawyers, and dismissed the Orange diocese list of its accused as irrelevant, saying he reached out to them but they never responded. And he also told reporters that molestation claims against Jimenez were so long ago that they’d be irrelevant even if they were true. “If something happened — if something happened — that there’s not a singe proof of [sex abuse] having happened,” the bishop proclaims on video,“It would’ve happened 40 years ago.”

Jimenez, for his part, claimed in a press release that John Jay researchers rejected the Orange diocese’s inclusion of him in their submitted list of their pedophile priests. In a subsequent television interview, Jimenez said there were no investigations against him in Peru or in the United States. His lawyer added: “There exists no investigations on the level of a prosecutor.”

A story that resonated on such a national scale should’ve caught a reporter’s attention in Orange County, or even among the American Catholic press. But in another sign of the decline of local news media, there has not been a single dispatch in the United States about Jimenez’s saga — until this one.

Never too late

And why do I care about some long-ago priest? Because I know the truth.

I covered the Diocese of Orange sex-abuse scandal for OC Weekly for nearly 15 years. When Jimenez's name was released in 2004, I immediately contacted friends who attended St. Mary and St. Anthony Claret who remembered “Padre Edgardo” — and who knew some of his alleged victims. But they refused to come forward because they were all Latino males who didn’t want to be pegged as “gay.” With no one willing to talk, I was never able to pursue the story.

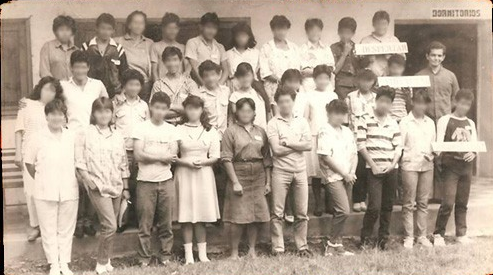

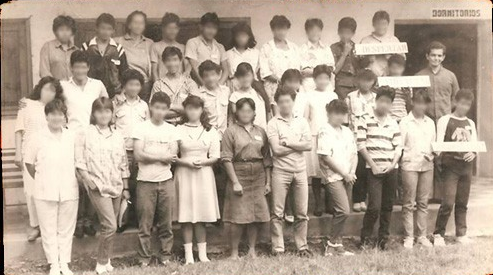

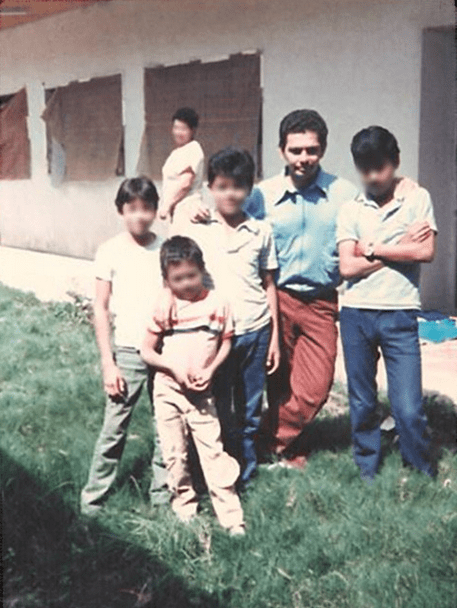

In 2009, I got a tip that Jimenez was still in ministry in Spain. I was also provided photos of him by a source that showed Jimenez at youth retreats in Honduras. I was finally able to write a story for OC Weekly, in which a friend disclosed that boys she knew “seemed to change after helping Father Edgardo.” Men who claimed Jimenez abused them privately thanked me for finally exposing him and the Orange diocese’s complicity — the local church had never filed a report with local authorities and let Jimenez flee the country — but these victims still declined to come forward.

In October, a producer for Cuarto Poder (“Fourth Estate”) contacted me for permission to use my photos of Jimenez. I hadn’t thought of him in nearly a decade, and was shocked when the producer told me he was still in ministry. I gladly gave the producer the photos, which they used in their report.

Knowing no American reporter would pick up the updated story, and that the Peruvian press would accept their claims with little pushback, I reached out to the USCCB, the Orange diocese, and John Jay College for comment about the claims of Bishop Simon and Jimenez. The Orange diocese, unsurprisingly, didn’t return my request for comment, because they haven't talked to me in over a decade; the USCCB spokeswoman Judy Keane suggested I reach out to the Chimbote and Orange diocese for comment.

John Jay professors were more forthcoming. Professor Karen Terry, who was the principal investigator for the 2004 study, disputed Jimenez's claims.“We did not have any contact with individual priests with allegations of sexual misconduct,” Terry wrote via email. “An individual priest would never have been able to identify whether he was included in our study or not.”

Another researcher, John Jay psychology professor Michele Galietta, said that “in no way would the study provide exculpatory evidence for any particular individual ... We did no such individual level investigation and could not have done so, given data we collected.”

The furor has died down in Peru, and Jimenez remains in ministry. His alleged victims cannot sue in civil court, because the statute of limitations ran out long ago. But they can still file a police report and try to pursue criminal charges.

To those haunted by Jimenez’s days in Anaheim and Fullerton, it's never too late.

* Archive images courtesy of the author.