[dropcap size=big]N[/dropcap]o one sings songs or makes movies about my Whittier Boulevard.

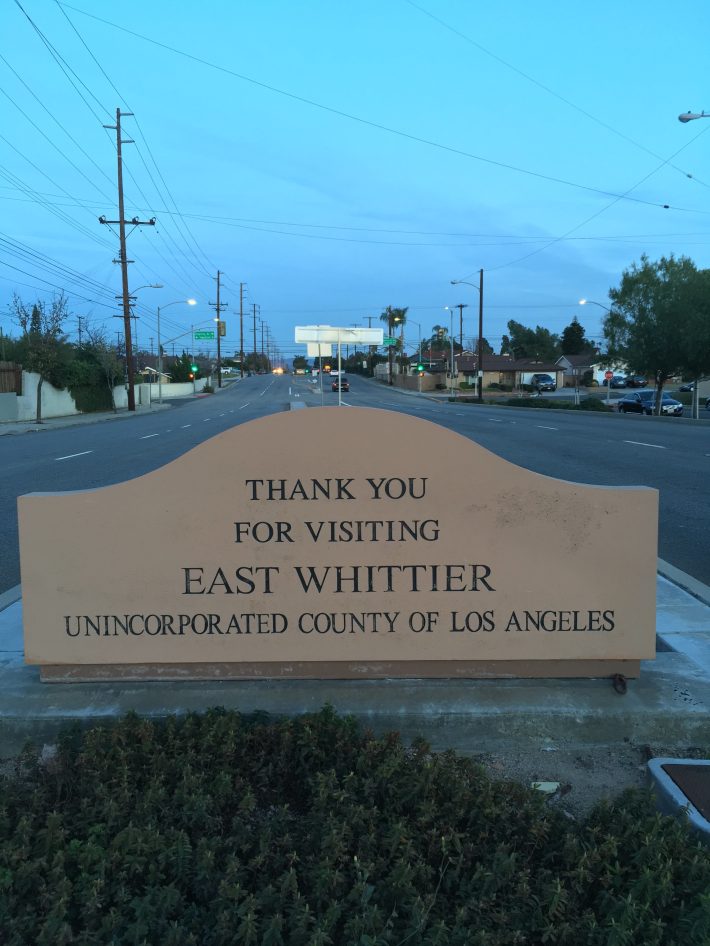

There’s no mythology around the days of zoot suits, classic lowriders, and Chicano movement marches. That’s because my Whittier Boulevard is not in East L.A. Mine is a deeper drive east. It snakes well past the 605 freeway. This is East Whittier before crossing into La Habra, Orange County. This is the Whittier Boulevard of the Orange County borderlands, one that often escapes the attention of history writers, culture makers, and culinary tourists. This is the Whittier Boulevard I remember fondly as a young “Mexican-American” growing up in the 1980s and 1990s in the Whittier-La Habra region of greater Los Angeles.

When I drive down Whittier Boulevard, I don’t see the same things Cheech Marin saw in the music video for his 1987 song, “Born in East L.A.” There’s no “Soto Street” or “Brooklyn Avenue” like he sings about. “City Terrace!” That’s where my mama’s from, before her family moved to Commerce and eventually, La Puente and Hacienda Heights, further east down the 60 freeway and over the hills — deep Eastern L.A.

In popular culture and our general L.A. Chicana/o-Latina/o imagery, Whittier Boulevard represents a sort of quintessential East L.A. Chicano nostalgia for back in the day, a popular statement used by many when referring to an era in time when cruising in custom cars defined social life on the historic thoroughfare.

The East L.A. band Thee Midniters paid homage to the famed boulevard in 1965 with their song, “Whittier Blvd.” In the 2013 book Spaces of Conflict, Sounds of Solidarity: Music, Race, and Spatial Entitlement in Los Angeles, UCLA professor Gaye Theresa Johnson writes about how the song “announces the relevance” of Mexican “traditions, history, and persons on the literal boulevard and the figurative landscape of postwar L.A.”

Thee Midniters open their instrumental track with the singer’s call to the listener — “Let’s take a trip down Whittier Boulevard!” — before mariachi-style gritos give way to a jovial melody of surfer-garage-rock guitars over Hammond organ-style mega chords played to the drum roll beat of jangly tambourines. It was classic Chicano music that became part of the soundtrack to the emerging movimiento.

Whittier Boulevard is the main branch of my family tree. It runs right through my childhood and adolescence and adulthood.

By the time Cheech’s video came out about two decades after Thee Midniters’ song, Whittier Boulevard had already been seared into my young Mexican-American mind as the street in East L.A. that my parents remember from their youth. I knew their Whittier Boulevard in passing, but it still wasn’t mine.

It was the street we drove through back to East L.A. to visit my grandparents, who lived in the same East L.A.-Commerce-Montebello area where I was born and where my parents grew up. The big move for us came in 1979, when my parents moved their young family eleven miles away to the “better schools and nicer areas” of suburban east Whittier and La Habra.

I’ll never forget when my dad showed me in the Thomas Guide where our new house was. “Look,” he pointed, “we’re here,” and traced his finger down Whittier Boulevard from Montebello through Pico Rivera, then turning the page to Whittier, our new hometown, “and our new house is here.” That part of the map was white, unmarked.

Unincorporated, but somehow still Whittier.

Our new house was two small lines on the map away from the Orange Curtain. On the other side was La Habra, Orange County, where my sisters and I would attend high school in the 90s.

Growing up just two streets away from La Habra in unincorporated East Whittier, L.A. County, meant growing up in the O.C./L.A. borderlands, a strange experience that left me confused about where, exactly, we lived. (Apparently, many others are still confused about the whereabouts of the region.) Back then, the only other people who knew streets like Lambert Road, First Avenue, and Santa Gertrudes were our schoolmates, neighbors, and the familia who came to visit us from “all the way out in the boonies.”

But even in a new place in a new part of town, Whittier Boulevard was familiar. I would come to know well the four-mile stretch between the two poles of my school-age existence: the Whittwood Mall (now the Whittier Town Center) and La Habra High School. That strip is a far cry from the Whittier Boulevard of my parents’ days when they’d meet at GarDuno’s or Chroni’s for chili dogs and pastrami sandwiches after school.

Driving up and down the other Whittier Boulevard now, I’m flooded with memories of the things that used to be there but aren’t anymore.

My sisters and I had Taco Bell, Penguin’s Frozen Yogurt (no longer there), Tony’s mall pizza, and the Green Burrito (still there) that was over the fence and across the street from our high school. We also had the Whittwood Branch Library, around the corner from the mall, where my mom worked and where my sisters and I listened to storytime, worked on school projects, and would eventually volunteer during summers in high school.

I see the updated Whittier Quad, with its new Vallarta Supermarket, but the same old Olive Garden across the parking lot. I see car dealerships, random furniture stores, many barber shops, several vintage clothing and antique stores, and a Norm’s diner. I see Chinese foot massage parlors, a Catholic gift shop called Morrissey’s (fittingly), and a “tropical fish store” that used to be the old Licorice Pizza-turned-Sam Goody record store that I worked at during high school.

It’s easy to miss the history of this street when you’re looking for the new Orchard Hardware, Sprouts market, or Sketchers shoe store on Whittier Boulevard. Look closely and you’ll see the bells of the El Camino Real, a reminder of what it was before Whittier Boulevard.

And I see my Trader Joe’s, tucked up on Colima, one of two roads over the hill to Hacienda Heights and the San Gabriel Valley. I see the building that used to house the Music Plus-turned-The Wherehouse record store, now a car stereo place.

In the early 1990s, my high school friends and I would wait in line at 3 a.m. at that Wherehouse for tickets that went on sale at 10 a.m. inside the popular record store, the only place in East Whittier, as far as we knew, that had a Ticketmaster that gave away the precious wristbands that determined whether or not you’d score tickets to The Cure, Depeche Mode, or Morrissey.

The Whittwood Branch Library has expanded significantly since I was a kid and remains the part-time workplace of my mama, whose personalized “READ” poster still hangs at Central library in Uptown Whittier. Growing up, on trips to the mall or the Mimi’s Café, it seems that the whole town — even David Hidalgo’s family of Los Lobos fame — knew my mama, the Latina lady from the library.

Importantly, the Vans store is still there, significant when I was in school for its directional purposes to and from La Habra High. If you had to pass the Vans store to go home, you lived in Whittier and probably went to Olita, Meadow Green, and Rancho Starbuck.

If you didn’t, you probably lived in La Habra or even better, “above the Boulevard” in La Habra Heights. The latter is L.A. County and was the home to all the rich kids who went to Macy and Jordan. To me, passing the Vans store meant I was almost home, relieved to be officially out of Orange County.

Vans is still there, but not the Whittwood Mall. Now, it’s just another cookie-cutter, open-air suburban Town Center with a Target, Kohl’s, and Chick-Fil-A. Where there was once the Whittwood movie theater and a Farrell’s Ice Cream Parlour is now a big yellow Buffalo Wild Wings. Que sad.

It runs through my veins.

It’s easy to miss the history of this street when you’re looking for the new Orchard Hardware, Sprouts market, or Sketchers shoe store on Whittier Boulevard. Look closely and you’ll see the bells of the El Camino Real, a reminder of what it was before Whittier Boulevard. After all, it was once an old mission road used by the Spaniards back in Junipero Serra’s day.

In 1906, the state placed 450 mission bells along the entirety of the route, several of which appeared along Whittier’s portion of Whittier Boulevard. The handful we see today are replacements of the ones removed by the California Department of Transportation in 1933 when they broadened the Boulevard. The mission bells of El Camino Real are part of a proud heritage celebrated by the City of La Habra and their “Boulevard of the Bells,” a.k.a., La Habra Boulevard.

Upon Whittier’s incorporation in 1898, the main boulevard was called “County Road” before developers paved it in the 1920s using sand and gravel from the San Gabriel riverbed. The section of Whittier Boulevard that extends from east Whittier to the OC line through La Habra to Brea was completed in 1926, after which it became part of the California state highway system with the designation “U.S. 101.”

Currently, that stretch of Whittier Boulevard carries part of California state route 72 and 39, where it ends at Harbor Boulevard at the La Habra/Brea line. After Harbor, the grand Boulevard gets downsized to “Avenue,” ending as a skinny nondescript suburban cul-de-sac in Brea.

Like Cheech, I also get excited about my Whittier Boulevard. As someone born in Montebello and raised in Whittier to parents who grew up in East L.A., Whittier Boulevard is the main branch of my family tree. It runs right through my childhood and adolescence and adulthood.

It runs through my veins.

Whittier Boulevard! ¡Orale!

The writer wishes to thank Nicole Schulert and the Whittier Public Library for their research assistance.