[dropcap size=big]T[/dropcap]hey say it never rains in South L.A. Somebody lied. Because some days, there’s a big old cumulonimbus cloud...but it’s only over you. We walk around with these clouds, the fog creating blinders to the point where we can’t see one another clearly anymore. Often times, we don’t even see the people closest to us beyond the haze of their trauma and pain

I remember the sound of the hallway at my family’s house when I was younger. It was a voice in a low mumble when he’d talk to himself. It grew more animated the longer we left him alone. Sometimes, I’d stand at the doorway to his room and watch the scene unfold. It was as if he really believed whoever he was talking to in his mind was there in the room with him. I’d have to yell his name to snap him out of it. Then his eyes would light up as he looked back at me. His mind returned to the room and, every time, I could tell from his smile he was glad to be there with me.

I used to think some people just recalled memories out loud because my family vowed to protect his mumbling secret. Only the adults in our family knew he was clinically diagnosed. I wasn’t let in on the secret until I got older. His condition was hidden to the point where we forgot. We acted like it wasn’t there and wouldn’t even discuss it with one another. As a community, we tend to tuck away anything that makes us seem weaker because we, black people, are fighting against so much. But this hiding is dishonesty.

My co-creator for “Sad-Ass Black Folk,” Joel Boyd, and I sat down at a coffee shop for the first time in January 2019. Joel had an idea: a web series about black mental health. From there, the two comedy writers actively working through our own anxiety while unemployed, created eight characters, a world, and a story that would eventually become "Sad Ass Black Folk." Through recalling our experiences with mental health in our community, we realized there was one common thread: Nobody was honest with us. As black folk, we have to be twice as good to get half as much so you can’t let them see you sweat, stress, or shed a tear. In our community, mental illness is categorized as a weakness that needs to be prayed away. What this leads to, and what we wanted to show on the screen, is suppression.

Through this journey, I began to recall my own experiences of suppression with depression and anxiety. Accompanying me on my way to school every morning in elementary school was a bubbling stomach ache that I blamed on swallowing toothpaste. In high school, it arrived in the form of being a “morning person” on the weekends. But it was neither toothpaste nor a chipper disposition; it was anxiety. Growing up, no one explained that there were clinical diagnoses for high-functioning, seemingly “normal” people. Only the “crazy” ones needed to actually tend to their brains. Sweeping “shyness” and tummy aches under the rug meant pretending everything was fine. Everything wasn’t fine and neither were the people around me.

We found out statistics, such as that only one in three Black Americans in need of mental health care receive treatment.

Our mumbling secret wasn’t the only one struggling in my life. I developed friendships with people that disappeared for months at a time and came back without warning. I had friends who made their mom answer the phone and say they were in the shower every time I called because they were afraid to tell any of us they had life growing in their belly before we even made it to high school. I had family members whose flared temper always embarrassed me in public. Let’s not forget the noble narcissists, the career swappers, and the conspiracy theorists that took their beliefs a bit too far.

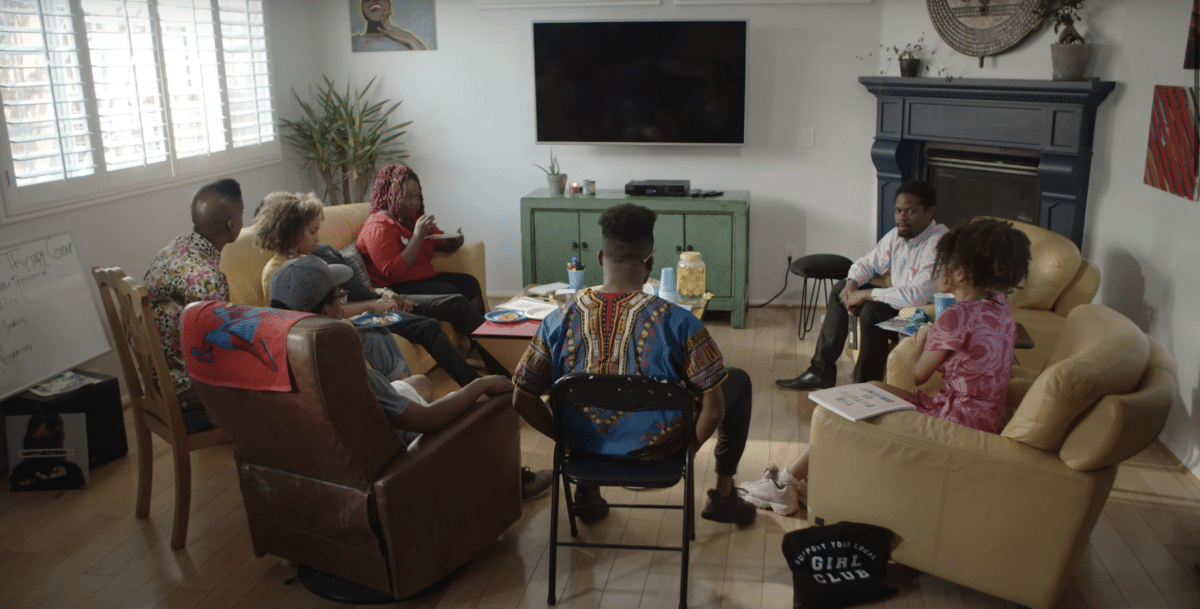

This truth is where our characters in the show came from—the people Joel and I knew, our family, and our friends. Joel and I asked ourselves: What would happen if we brought all of these people we knew together for the purpose of healing? Further, we wondered: Would the person leading this healing be flawed as well? From there birthed the premise of “Sad-Ass Black Folk.”

After deciding grad school is wack, Preston, a socially inept, aspiring black psychologist, brings together a group of south L.A. misfits for a homemade group therapy “case study,” only to discover his own demons. He finds it difficult to usurp control of a sour-patch sidekick, a trust fund scammer, a sanctimonious activist, an EBT queen, an Eeyore sadboy, a nerdy hermit, and a hood hippie who are all battling serious inner issues. After encouraging these “patients” for weeks to be honest with themselves, they ultimately discover he’s been hiding what he’s going through more than them.

We want to normalize wellness, therapy, and healing and reverse the idea that there’s something shameful or wrong with people struggling with depression, anxiety, or serious psychological issues.

When we began interviewing black mental health specialists, Joel and I instantly felt less alone. We found out statistics, such as that only one in three Black Americans in need of mental health care receive treatment. However, Black Americans are 20 percent more likely to report serious psychological distress than adult whites. Clearly, our families weren’t the only ones evading the conversation on mental illness because not enough black folk are seeking or have access to help. The stigma, the suppression, the dishonesty, the mistreatment of black folk by specialists, and the misinformation keeps all of us from realizing we aren’t alone. So we process it through escaping in relationships, like Serenity in Episode Two. We run from our past without addressing our trauma like Jordyn in Episode Seven and Amira in Episode Five. We experience being hurt even more when asking for support by those we love like Aspen in Episode Four. We search for thrill in reckless behavior like Thad or decide to finally give up like Carl in Episode Three.

And so, beyond the web series, our mission became to create conversation and community through resources and events. We made sure the show reflected blackness in all of its expansiveness within Los Angeles in particular. We ultimately created this narrative, straight from our hearts, in the hopes that we’d make people laugh, start a conversation, and create a platform for healing.

We want to normalize wellness, therapy, and healing and reverse the idea that there’s something shameful or wrong with people struggling with depression, anxiety, or serious psychological issues. Since the journey, I’ve had friends and family start going to therapy. We’ve created events to prompt healing and community. And a year after that first coffee shop meeting, you can now watch all eight episodes on YouTube.

We will be kicking off the Free Minds Festival in Leimert Park on April 24th to continue to spread healing in South Los Angeles.