Welcome back to L.A. Taco’s new column, “Barrio Wisdom.” In this new series, we follow the streets-meet-academia wisdom of Dr. Álvaro Huerta, a professor at California State Polytechnic University, Pomona. In this installment, we read a follow-up to last week’s feature on how growing up in the inner-city housing projects can teach you to be a better person.

[dropcap size=big]L[/dropcap]ife was difficult for my siblings and I growing up in East Los Angeles’ notorious Ramona Gardens housing project—also known as Big Hazard projects for the dominant gang. It was also memorable, as we also grew up having fun with a bunch of kids just like us: Mexican, poor, and resilient. While I have horrific memories that I wish to erase from my mind, I will always cherish the good memories. I only wish that my beloved brother Noel (or Nene) was still alive to reminisce on the latter.

As I share these memories (or stories) with the world (or the five people who will read them!), I want to confirm that they’re all true. There are few instances, however, where I employ some creative license, as noted by an asterisk. Moreover, unlike police informants and snitches, I won't name names or discuss anything that may implicate or embarrass anyone involved in illicit behavior. This is no implication that I shy away from the dark side of the projects. Overall, however, I’m more concerned with shining light on the positive traits and characteristics found in America’s barrios, like the significance and reliance of interpersonal networks (or strong ties), trust, reciprocity, loyalty, dignity, and respect.

On welfare

In the projects, virtually everyone was on welfare (or government aid), food stamps, and Medical. We received our welfare checks on the 1st and the 15th of the month. We referred to these holy days as Mother’s Day. I memorized these glorious days because it was the only time we ate the good cereal with sugar, like Lucky Charms, Trix, and Fruit Loops. I hated the regular Kellogg’s Corn Flakes! That tasted more like prison food; bland and soggy. It needed a ton of crunchy sugar in the form of added spoonfuls for it to taste good. It also got soggy with the milk. The more kids in the family, the more government aid the parent(s) or guardian(s) received. Luckily, my parents had eight kids, so we hit the lottery! $8,000.00 per year, as I documented in my FAFSA application while applying to UCLA.

While I was embarrassed to use food stamps, which arrived in packets, I always counted the days for the fake money to arrive in the mail. Since my parents didn’t have a bank account or access to nearby banks, like Bank of America or Wells Fargo, my mother cashed the checks at Nico’s Meat Market (or Nico’s). Owned and operated by an Indian American family—not to be confused with American Indians or Native Americans—they connected with the rest of the brown community in their store’s radius.

The more kids in the family, the more government aid the parent(s) or guardian(s) received. Luckily, my parents had eight kids, so we hit the lottery!

It helped that they spoke three languages: their native tongue, English and Spanish. The patriarch Salim cashed the residents’ checks without requesting identification cards. Nobody messed with Salim, including the homeboys, since he practiced one of many rules in the projects: Treat everyone with respect. Shopping at Nico’s was like the theme song to the old television show, Cheers: “Where everybody knows your name / And they're always glad you came…” Like miners relying on the company store, while the residents benefited from Salim’s store credit, by the time they cashed their welfare checks at Nico’s, they owed most of it (or all) to Salim. Don’t you just love small business capitalism?

Margarita’s popsicles and sandwiches

In the projects, it seems like everyone had a side-hustle—a way of making extra money or securing goods and services to survive. This is why the informal economy is instrumental for the marginalized. Margarita (pseudonym), who lived adjacent to “our” apartment building, sold popsicles. She made all flavors: cherry, strawberry, and vanilla. She even had mango and tamarindo. She charged a nickel. She made a killing during the hot summers. She also sold peanut butter and jelly sandwiches for a dime. Since my siblings and I had weekly allowance (or Domingo) of a whopping twenty-five cents (thanks a lot, dad!), I occasionally frequented Margarita’s establishment. Her establishment represented her kitchen, where we knocked on the back door and waited for her to take our orders.

That’s the problem with childhood nicknames in the projects: You can be 50 years old and you’re still referred to as Chubby (for being a “big boy”), Flappers (for having big ears) or Milk (for being light-skinned).

Apart from Margarita, there was one Mexican woman who sold tamales. (There’s at least one in every barrio!) I felt bad for her teenage son who helped her sell tamales at Hazard Park. We called him “Tamale.” Many years later, I think he’s still called that. That’s the problem with childhood nicknames in the projects: You can be 50 years old and you’re still referred to as Chubby (for being a “big boy”), Flappers (for having big ears) or Milk (for being light-skinned).

Peanut butter*

Margarita had one son. We called him Peanut Butter. While we were childhood friends, to this day, I also don’t remember his real name. Being an only child with no father to protect him, Peanut Butter was easy prey for the bullies. It didn’t help that he was skinny, shy, and wimpy. “Hey, leave Peanut Butter alone,” I remember telling a schoolyard bully at Murchison Street School. Tomás (pseudonym), who thought he was tough because his older brothers belonged to the gang, always picked on Peanut Butter. “Peanut Butter,” Tomás once said, “Go to the top of the roof and jump.”

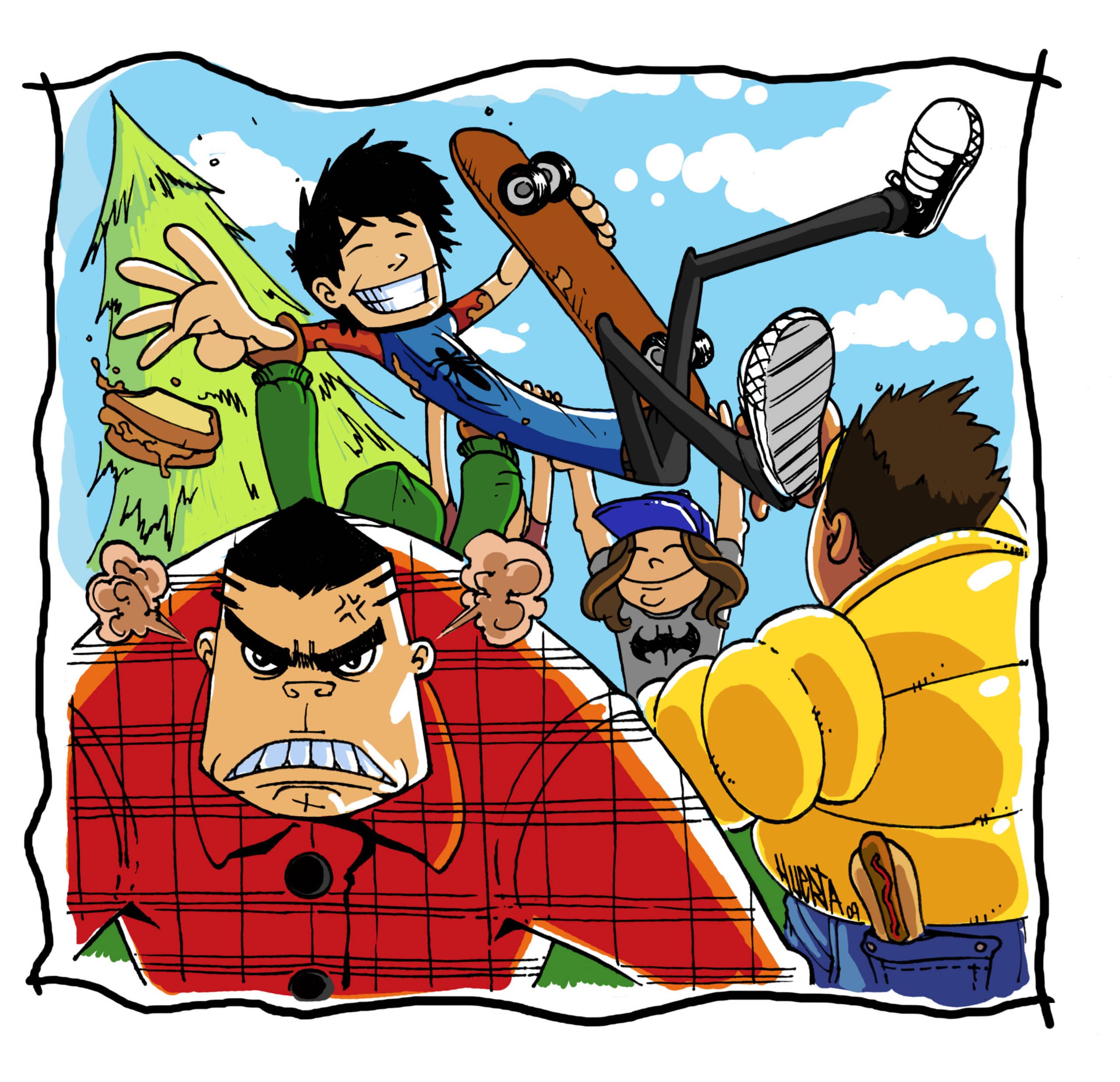

Without saying a word, Peanut Butter climbed up to the roof through the windows and jumped. Since he wasn’t very athletic, he fell on his face and ran in tears to his apartment unit. A bunch of kids witnessed his fall without saying a word or taking action since they feared Tomás. On another occasion, Tomás told Peanut Butter to jump down the stairs on his skateboard, like the late daredevil Evel Knievel. Once again, Peanut Butter fell on his face and started to cry. Peanut Butter never learned the rules of the mean streets! To paraphrase Tom Hanks’ character in the female baseball movie, A League of their Own (1992), “There’s no crying in the projects!”

On one occasion, Tomás commanded Peanut Butter to climb up a large tree to the top. Like a good soldier, Peanut Butter carried out the orders, where he only got half way to the top. As he looked down, he noticed the same crowd of kids forming to watch the spectacle, including myself. Panic slowly overtook him, as he clinched onto a thin branch. A strong wind came out of nowhere. Fearing for his safety, we started to yell in unison, “Peanut Butter, come down! Peanut Butter, come down!” Suddenly, the branch snapped! He fell on his back. He gasped for air. Instead of remaining on the sidelines, this time the crowd turned against Tomás. After shunning Tomás, we lifted Peanut Butter off the ground and carried him to cheer him up. Instead of crying with pain, he was smiling with joy. As a reward, I gave him my peanut butter sandwich that I bought from his mom Margarita.