For many, it happened quickly; for others, the day couldn’t come soon enough. Now that unhoused residents in Little Tokyo have been cleared from Toriumi Plaza, what will come of the legacy of long-standing businesses like historic mochi shop Fugetsu-do, one of a handful who called for the banishment of the poor and unhoused from a historically politicized and gentrified neighborhood?

On Thursday, March 17, approximately 20 unhoused residents were swept from their encampment, many of whom had spent the last 11 months to three years on 1st and Judge Aiso Streets to make a home during the first waves of the pandemic. Over the last month, many of them left on their own accord to avoid being moved into 90-day A Bridge Home shelters, temporary rooms by way of Project Roomkey, or new tiny home villages in Councilmember Kevin de León’s district that come with strict rules and curfews.

“Since [de León] took office, housing has been his focus,” said Pete Brown, Kevin de León’s communications director, “so this is not anything new that we are doing. This is an ongoing effort. Everybody deserves to be housed. It’s not progressive nor humane to allow people to live on the streets and die on the streets like this.” For Romey, an Angeleno who had been residing at Toriumi Plaza for around 11 months, housing services provided by the City do not feel genuine. “I’m not going to a program or something because that’s not what I want,” he said. “The program is only for people who will abide by what they want to do to their benefit. They're going to tell you to be in by 10 PM, you have to be at bed count. They’re not really trying to help you; they’re just trying to get their profits in their pocket.”

De León’s removal of the community at Toriumi Plaza wasn’t supposed to happen abruptly. During the last week of February, activists and cultural organizers on the ground in Little Tokyo were hopeful about a community-driven meeting with Councilmember Kevin de León about the encampment of unhoused residents on Toriumi Plaza. A meeting never came; by the end of the month, de León’s office confirmed with residents that an official sweep and fencing of the plaza will happen on March 17.

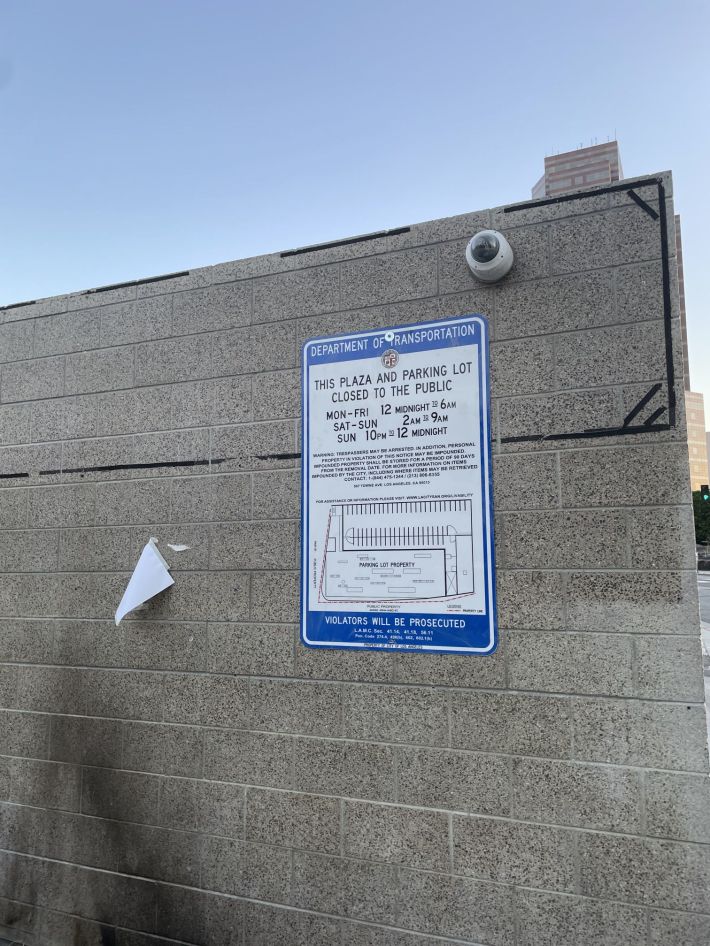

“There was not a recent request for a meeting or anything,” said Pete Brown, Communications Director for Kevin de León. “And again, this was an operation that has been going for 4 to 5 weeks, and from the onset, everybody was notified of the closure of the site to allow for repairs to this property, which is the Department of Transportation's property.”

The rumored meeting was going to be an opportunity to highlight the inhumanity behind L.A. Municipal Code 41.18, which deems it unlawful for a person to sit, lie, sleep, or place private property in public rights-of-way within a designated distance of properties and facilities. All those who violate the ordinance would be forcibly removed, an action that often gets quickly escalated by LAPD. For volunteer-run Jtown Action & Solidarity, a group that holds weekly Power Up services and advocates for unhoused rights and anti-gentrification, LAMC 41.18 is used to benefit people with wealth and power who aim to privatize public space, which harms unhoused human beings in the process.

“I worry about the residents and their safety,” said Zen Sekizawa of Jtown Action & Solidarity. “I’m afraid that they might get kicked out or their program ends because there are no services, so they’re left with just carceral shelter. It’s so difficult for these folks to move out of their own community. They have such a fragile survival system set up, and once you totally damage that fragile system, it’s really awful.”

A community meeting was first alluded to in a Little Tokyo community council meeting on February 22. In the meeting, Fuegtusu-do’s owner Brian Kito—representing the Little Tokyo Public Safety Association, the Little Tokyo Business Improvement District, and merchants—vied to “take Toriumi Plaza back for the community” as the encampment was becoming too violent and that the area needed to return to place for those in the area to sit and enjoy lunch breaks.

“We’re very sympathetic to the pandemic and what everybody had to go through, but it became very clear after a couple of months—with the issues with the encampment—that the surrounding areas were suffering,” Kito told L.A. TACO, citing assault and property damage that he claims can be linked to people who were living in the encampment. “It was pretty clear that the community was taking the brunt of all the vandalism.” Kito’s Fugetsu-do, one of the most popular and critically acclaimed pastry shops in Los Angeles, lies less than a block away from the Toriumi Plaza. The mochi shop owner’s proximity to the encampment has informed his point-of-view on the plight of the community.

“The truth of the matter is that we have to live with this 7 days a week, 24/7,” said Kito, comparing his perspective from that of Jtown Action & Solidarity. “It’s a whole different thing to have to see this place 24/7 versus coming by just once a week or here and there.” At one point, Kito had reached out to a few of the residents on Toriumi Plaza. “I asked them, ‘Is there something you can do about policing yourselves?’ They actually shook my hand and said ‘Thank you for coming to talk to me directly.’ I left it at that, but then the rock-throwing and window breaking continued.”

Romey recounted a different experience about the area he has called home for almost a year. Toriumi Plaza was a peaceful place to stay sober and keep to himself.

“[People] want to get away from one area because of thieving or whatnot so they move somewhere else,” Romey explains. “They introduce themselves to a new area and ask if it is all right if they move here. Sometimes we go see what happened with where they was [sic] at and make sure they weren’t thieving. And if you were, quite naturally we wouldn’t want you here - that’s the laws of the homeless people.”

According to LA City’s crime data from 2020 to current, the area has not seen a significant reported increase in the reporting district that surrounds Toriumi Plaza and the nearby popular sites like the Japanese Village Plaza—a 3% increase from 2020 to 2021. Based on recent community council meetings and conversations with merchants, Jtown Action & Solidarity posit that local businesses were using crime data to rationalize the sweep, though there may be no tangible evidence that any crimes were linked to the residents in the encampment.

Regardless of crime data, Kito has lurid accounts of the status of the neighborhood. “We have activists who are [at Toriumi Plaza] on Saturdays only to bring down food and charge their batteries for their phones, but they’re also giving them needles,” he said. “Needles are showing up all over the place in Little Tokyo so much so that we don’t have any mailboxes anymore because they’re finding needles inside the mailboxes.”

In response to Kito’s claim, Jtown Action & Solidarity group said, “In partnership with LA Community Health Project, we are able to distribute lifesaving harm reduction supplies such as clean kits, Narcan, fentanyl test strips, condoms, as well as sharps containers so people can safely dispose of their used needles. It’s not surprising that someone like Kito, who wants to criminalize everything, doesn’t see that we are actually alleviating some of the things that he’s complaining about. Also, people’s lives are more important than mailboxes.”

Other members are concerned that Kito’s words, as seen from his participation in the February 22 council meeting, has been approaching the banishment of the encampment with pro-police solutions while also using anti-Black rhetoric to compare the current “crime rate” in Little Tokyo to that of the early 90s “right after the Rodney King riots,” an era in Los Angeles when LAPD was under incredible scrutiny for racist policing practices.

In opposition, Jtown Action & Solidarity has also pushed on the hypocrisy of such claims from Kito, given his well-guarded history: the owner of the iconic Fugetsu-do shop was arrested in 1990 for conspiracy to distribute and possess with intent to distribute cocaine. According to a front-page report from the Hawaii Star Bulletin on April 6, 1990, Kito had approached a close associate to longtime crime figure Clarence “Japan” Handa about marketing cocaine. The article states that he was “looking for someone who could distribute kilogram quantities of cocaine in either Hawaii or Japan.” Kito was sentenced to one year and one day of imprisonment, four years’ supervised release, and a $10,000 fine. After returning to Little Tokyo to run his business, Kito worked actively with the Little Tokyo Koban, a volunteer-run public safety organization specializing in security and LAPD relations in the neighborhood. In 2017, President Obama pardoned the mochi baker for his 1990 crime.

Sekizawa argues that drug use is not what makes a person dangerous, as there are housed people who use drugs; however, the only people who are treated as a danger for their drug use are those who are Black, Brown, or poor. To Jtown Action & Solidarity, what makes Kito’s treatment of unhoused Angelenos who use drugs hypocritical is his own history with drug trafficking. To the group, it is only a problem for merchants like Kito when it is done by somebody without the privacy of walls or a roof over their heads.

Kito has no comment regarding Jtown’s assertion that his own illicit drug trafficking attempt belies his endeavor to rid Little Tokyo of drug use.

Above all, Jtown Action & Solidarity is most concerned by Kito’s adamancy to remove those who have been cared for by community members in Little Tokyo. For over 60 weeks, the group has been providing food, care, and resources to those in the area at their weekly Power Ups, all while de León’s office prepared for their sweep operation in recent weeks. Organizing members are concerned that representatives of the neighborhood who know Little Tokyo’s history of discrimination are dealing with the mistreatment of unhoused individuals with historical amnesia. For Jtown Action & Solidarity, calling for a sweep of a community that had been protecting each other from housing instability was akin to the historical events that happened around 100 years ago when residents were displaced and incarcerated when Executive Order 9066 turned 1st Street into a holding area for Japanese American incarceration.

“I’m concerned about this fence going up because it symbolizes much more than just fencing off the plaza,” said Sekizawa. “It symbolizes that this community is okay with this happening. Eighty years ago it happened to us, and we’re letting it happen right in our backyard. I’m concerned about what this community really represents and who is representing it.” Regardless of local merchants and residents who have been concerned enough to write to de León’s office, the team behind the L.A. mayor candidate insists that the March 17 sweep was a part of their plan.

“The effort to get people housed isn’t driven by local merchants or businesses,” said Brown. “It is driven by the humanity of it: to make sure that people aren’t living and dying on the streets and get the support services that they need. The fact is that the residents, merchants, and people who work in the area have concerns, but that’s not the driving force. The driving force is the humanity of getting people where they need to be, and giving them the dignity that they deserve.” Merely four weeks ago, there was a neighborhood council meeting, and on-the-ground organizers thought time was on their side to protect their unhoused neighbors. As of Monday, March 21, Toriumi Plaza remains fenced off to the public, an opposite result from what Kito had envisioned in the February 22 council meeting when he said he wanted to take back the area.

Meanwhile, Jtown Action & Solidarity proceeded with their weekly Power Up outside the now fenced-off Toriumi Plaza two days after their sweep defense. “Things are no different from before,” said Steven Chun, a member of Jtown Action & Solidarity. “Even those who accepted 'housing' from the city returned to the Power Up [...] because the community and relationships we’ve built are irreplaceable. As long as this city is failing to meet people’s basic needs, we will continue our Power Up—no matter how hard Kevin de León and the city try to put out the flames of our radical love for our people in Little Tokyo.”

After Thursday, Romey chose not to accept interim housing or enter Project Roomkey from the City. He relocated to somewhere else within Little Tokyo to remain close to the services and network with which he was familiar.

“I let God be my guidance and I live day by day,” said Romey. “I can’t plan for something that I don’t even know if I’m going to be alive for. I can only plan for now.”