This article was produced by Capital & Main, which is an award-winning publication that reports from California on economic, political, and social issues. L.A. TACO is co-publishing this article.

En la parte de abajo podrás encontrar una versión de este artículo traducido en Español.

[dropcap size=big]O[/dropcap]n January 4, 1892, Los Angeles politicians were in the city papers griping about tamal wagons. Again. “The ‘tamale’ wagons on the street corners the [street maintenance] Superintendent thinks should be made a thing of the past,” the Los Angeles Times reported. The wagons scattered throughout the Downtown area were still legal, despite the city council’s best efforts to limit their hours or ban them outright. Permits cost $1 every three months.

Nearly 130 years later, arduous health codes and vicious enforcement by health inspectors and police officers continue to torment vendors in the underground economy. But on April 20, the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health (DPH) gave the green light to a new tamal cart designed by Richard Gomez, a food truck engineer who grew up street vending and has worked for years to develop a code-compliant vending cart. In approving the 21st-century tamal wagon the DPH made critical concessions on refrigeration, waste, and sink requirements, indicating some welcome flexibility over health rules that vending advocates blame for sabotaging vending legalization efforts.

Gomez had nearly given up hope as the county rejected design after design, he told Capital & Main and L.A. TACO last fall.

“It's pretty much the ice cream cart that you see rolling on the streets,” a happy Gomez says of his design. “It’s like a breakfast cart, for people to get a quick bite before they go to work or drop off their kids at school.” (The model, selling under the name Revolution Carts, is available for preorder online and on Instagram.)

Gomez’s success bodes well for designers in a county pilot program currently trying to build an affordable, permitted food cart for vendors conducting “full food preparation,” the ultimate prize for vending advocates in the city’s vending certification wars. Until the DPH approves cooking and food handling at the sidewalk level, street vending is essentially illegal.

The Los Angeles City Council voted to legalize street vending in 2018 after lawmakers decriminalized vending at the state level. But for L.A. vendors preparing food, it proved essentially impossible to pass health inspection because the state health code was written for brick-and-mortar restaurants. The code makes substantial demands of vendors with $10,000 annual incomes, like three-compartment sinks, a handwashing sink and refrigeration space.

This fall, Gomez submitted a design for a tamal cart he thought was sure to pass inspection, but the DPH rejected it, asking him to include space for a microwave to keep the tamales hot.

That was “a cold bucket of water,” Gomez told Capital & Main and L.A. TACO when interviewed in February. “It was so much time put into this.”

The bureaucratic battles over cart permitting have high stakes for Los Angeles’ 10,000 vendors. Without approved carts, vendors cannot get permitted, but the DPH has continued its enforcement of unpermitted vendors, confiscating food in disastrous raids often conducted in collaboration with law enforcement. The city of Los Angeles has paused its enforcement until next year as the county pilot program concludes.

The Kounkuey Design Initiative, a community development and design nonprofit contracted by the county, has submitted its own cart to the Department of Public Health, according to Lyric Kelkar, policy director for vending nonprofit Inclusive Action for the City, which is assisting with the project. Kelkar says they are awaiting revisions from the DPH.

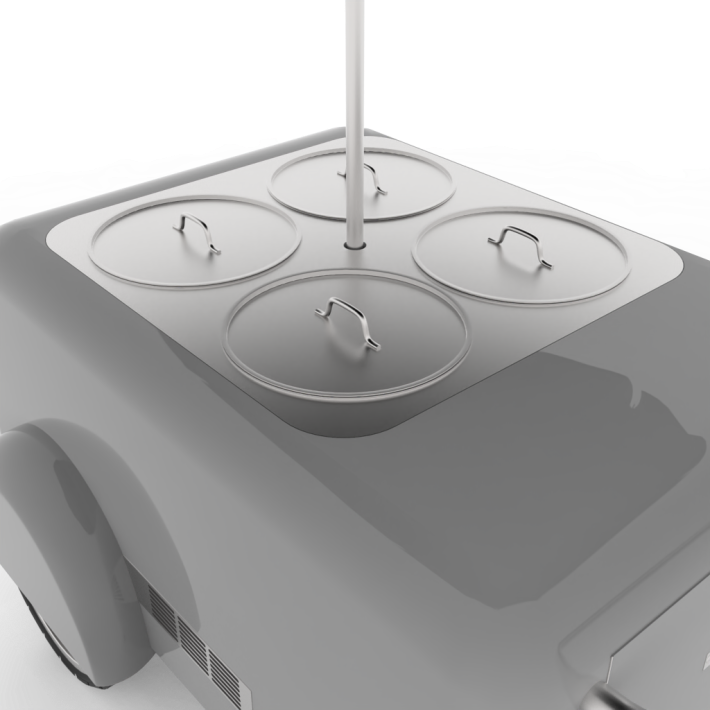

Gomez’s approved design has no microwave, no sinks, and can carry 336 tamales across four steam buckets, each with a capacity of seven dozen. The fiberglass carts come in a variety of colors, including Dodger Blue and the dark green of the Mexican flag.

As Gomez submitted his designs, the county made its usual demands for three-compartment sinks, storage, and refrigeration, among other asks like microwaves and sanitizer buckets. “Each one of those things we challenged,” he says. “We went back to the original code and challenged.”

As the Kounkuey Design Initiative finalizes its cart, Inclusive Action for the City is following the same playbook with county representatives, according to Kelkar, closely analyzing the state health code and arguing for concessions.

The new tamal cart costs “in the $7,500 range,” according to Matt Geller of the National Food Truck Association, who fought alongside Gomez to get it approved. Some market options for tamal carts do exist, but are significantly larger to accommodate waste units, sinks, and refrigerators, and cannot be pushed down a sidewalk. They are also more expensive: one tamal cart designed by Kareem Carts, a Los Angeles-based manufacturer, sells for $12,000.

Inclusive Action for the City will be offering loans to vendors to acquire the new tamal cart, according to Geller. “Our hope is that we can get these carts in the hands of vendors with no money down,” he says.

L.A.’s First ‘Legal’ Street Food Vending Tamal Cart Will Cost Around $7,500. Here’s a First Look at the Revolutionary Design

“The more carts the better, especially if those carts will help vendors become legit in this industry,” says Sergio Jimenez, an organizer with the Community Power Collective, another vending advocacy nonprofit. “The cost is, I think, too much for just keeping the temperature constant, but perhaps with city and county funding, those carts could definitely be used.”

For vendors who can lose thousands of dollars when their carts are confiscated by the health department, the approval is a small glimpse of what they hope is to come. This year, vendors who spoke with Capital and Main and L.A. TACO said they were open to purchasing a cart that would be approved by the health department so long as it was not too big and not too expensive.

Street vendors like Juana Dominguez, who currently sells quesadillas and tacos on Main and 41st streets in Los Angeles, are open to the idea of purchasing a cart that would pass DPH’s brutal inspections. The 52-year-old vendor has been street vending since before she arrived in the U.S. She started out 10 years ago, selling candy and gum before eventually being able to afford a cart for tacos.

Dominguez recognizes the need for a county-approved cart. In the last couple of years, she has had her carts taken away three times. Losing her first cart, a combination grill, and refrigerator set-up, cost her and her husband $3,800.

“Me da mucho gusto that there finally is a cart, because it hasn’t been easy for many vendors,” she said, smiling, after seeing a picture of the design.

Although the design done by Gomez does not apply to Dominguez as a vendor who sells tacos, she is happy. She said she once sold tamales too and understands the difficulties those vendors face. “Me salía a vender en las fábricas,” she says. “I would go out and sell in the factories.”

To keep her tamales, which were made at home, warm, she’d cover her pot with plastic and a cloth to keep the steam flowing, then strap the pot to a wheeled cooler. When asked what she thought of the price of the newly designed tamal cart, she said something similar to what she said back in March.

“If it comes with the permisos (the permits), it’s great, because that makes the price of the cart not look so bad, but if we still need to purchase permits on the side after getting the cart it may be difficult for some vendors,” she said, referring to vendors who are recovering from the pandemic. “But we understand that it’s a step forward.”

Her main concern was having to pay a monthly or hourly fee at a commissary: DPH-approved kitchens where vendors can pre-prepare food before going out to sell. The state health code demands that a variety of foods — like tamales — be prepared only at commissaries. Even fruit vendors are not technically allowed to slice fruit on the street and can do so only in an approved kitchen. According to Lyric Kelkar, fees can be anywhere from $20-$32 an hour. An overnight stay could cost up to $200, around what a vendor makes in a day of work.

“See, that’s something to take into consideration, because it’s an extra bill for us, not to mention not every vendor has transportation to be going back and forth,” says Dominguez.

Beverly Estrada from At Bev’s Tamales, who sells near USC, says she’s already in line to purchase one of Gomez's creations. “I'm waiting for mine,” she says with excitement.

The 42-year-old vendor sells traditional Mexican tamales, including chicken tamales and birria tamales accompanied by a cup of consommé (broth). She has been selling for a little over a year and has already been given verbal warnings from the health department. Currently, without a permit, she cooks in a pot at home with a small burner and propane tank. For big orders, the vendor vacuum seals her tamales.

“I think it's gonna be an awesome opportunity for street vendors like myself because, to be honest, sometimes it feels like we don't have a lot of support,” she said. “The cart gives vendors a bit of hope, and now it’s here.”

Juana Dominguez is already looking forward to the county approving more designs.

“I hope a grill cart is next,” she says.

--

Conoce el Diseño Revolucionario del Primer Carrito ‘Legal’ de Venta de Ambulante de Tamales en Los Angeles Que Costará $7,500

Capital & Main, publicación galardonada que informa desde California sobre asuntos económicos, políticos y sociales, produjo este artículo. L.A. TACO lo publica en colaboración.

El 4 de enero de 1892, los políticos de Los Ángeles estaban en los periódicos de la ciudad quejándose de los carritos de tamales. Nuevamente. «El superintendente (de mantenimiento de calles) piensa que los carritos de tamales en las esquinas deberían ser cosa del pasado» informó Los Angeles Times. Los carritos esparcidos por la zona del centro de la ciudad seguían siendo legales a pesar del gran esfuerzo del municipio para limitar las horas o prohibirlos completamente. Los permisos costaban $1 cada tres meses.

Casi 130 años más tarde, los arduos códigos de salud y la imposición despiadada por parte de los inspectores de salud y la policía siguen atormentando a los vendedores en la economía sumergida. Sin embargo, el 20 de abril, el Departamento de Salud Pública (DPH, en inglés) del Condado de Los Ángeles aprobó un nuevo carrito de tamales diseñado por Richard Gómez. Richard es un ingeniero de camiones de comida que creció vendiendo en la calle y ha trabajado durante años para desarrollar un carrito de ventas. Al aprobar el carrito de tamales del siglo XXI, el Departamento de Salud Pública hizo concesiones críticas sobre los requisitos de refrigeración, desechos y fregaderos, lo que indica una buena flexibilidad sobre las reglas de salud que los defensores de la venta ambulante culpan por sabotear los esfuerzos de legalización de la venta.

El otoño pasado, Gómez le dijo a Capital & Main y L.A. TACO que casi había perdido las esperanzas cuando el condado rechazaba los diseños uno tras otro.

«Es más o menos el carrito de helados que ves andando por las calles», dice Gómez, feliz con su diseño. «Es como un carrito de desayuno para que las personas coman algo rápido antes de ir a trabajar o a dejar a sus hijos en la escuela». (El modelo, que se vende con el nombre Revolution Carts, se puede reservar en línea y en Instagram).

El éxito de Gómez es un buen augurio para los diseñadores en un programa piloto del condado que actualmente intenta construir un carrito de comida asequible y permitido para los vendedores que realizan una «preparación completa de alimentos». Este es el premio máximo para los defensores de la venta ambulante en las guerras de certificación de venta ambulante de la ciudad. Hasta que el Departamento de Salud Pública apruebe que se puede cocinar y manipular alimentos en la calle, la venta ambulante es esencialmente ilegal.

El municipio de los Ángeles votó a favor para legalizar la venta ambulante en el 2018 después de que los legisladores despenalizaran la venta a nivel estatal. Pero para los vendedores de Los Ángeles que preparaban comida, resultó prácticamente imposible pasar la inspección de salud porque el código de salud estatal fue escrito para restaurantes tradicionales. El código impone demandas importantes a los vendedores con ingresos anuales de $10,000, como fregaderos de tres compartimentos, un fregadero para lavarse las manos y un espacio de refrigeración.

Este otoño, Gómez presentó un diseño para un carrito de tamales que pensó que seguramente pasaría la inspección, pero el Departamento de Salud Público lo rechazó y le pidió que incluyera espacio para un microondas para mantener calientes los tamales.

Eso fue «un balde de agua fría», dijo Gómez a Capital & Main y L.A. TACO cuando fue entrevistado en febrero. «Se ha dedicado mucho tiempo a esto».

Las batallas burocráticas sobre permitir los carritos tienen mucho en juego para los 10,000 vendedores de Los Ángeles. Sin carritos aprobados, los vendedores no pueden obtener el permiso, pero el Departamento de Salud Pública ha continuado con la aplicación de la ley de vendedores no autorizados. Confiscan alimentos en ataques desastrosos que generalmente se llevan a cabo en colaboración con la policía. La ciudad de Los Ángeles ha detenido esta imposición hasta el año que viene cuando concluya el programa piloto del condado.

Kounkuey Design Initiative (organización sin fines de lucro de desarrollo y diseño comunitario contratada por el condado) presentó su propio carrito al Departamento de Salud Pública, según Lyric Kelkar. Lyric es directora de políticas para la venta sin fines de lucro de Inclusive Action for the City y que está ayudando con el proyecto. Comenta que están esperando revisiones del Departamento de Salud Pública.

El diseño aprobado de Gómez no tiene microondas ni fregaderos y puede tener 336 tamales en cuatro cubetas de vapor, cada una con una capacidad de siete docenas. Los carritos de fibra de vidrio vienen en una variedad de colores, incluidos el azul de los Dodgers y el verde oscuro de la bandera mexicana.

Cuando Gómez presentó sus diseños, el condado hizo sus demandas habituales de fregaderos de tres compartimentos, almacenamiento y refrigeración, entre otros pedidos, como microondas y cubetas desinfectantes. «Desafiamos cada una de esas cosas», comenta Gómez. «Volvimos al código original y lo desafiamos».

A medida que Kounkuey Design Initiative finaliza su carrito, Inclusive Action for the City está siguiendo la misma estrategia con los representantes del condado. Según Kelkar, analizan de cerca el código de salud estatal y defienden las concesiones.

El nuevo carrito de tamales cuesta «aproximadamente $7,500», según Matt Geller de National Food Truck Association, quien luchó junto a Gómez para que se aprobara esto. Existen en el mercado algunas opciones para los carritos de tamales, pero son mucho más grandes para acomodar unidades de desechos, fregaderos y refrigeradores, y no se pueden empujar por la acera. También son más caros: un carrito de tamales diseñado por Kareem Carts, fabricante con sede en Los Ángeles, se vende por $12,000.

Según Geller, Inclusive Action for the City ofrecerá préstamos a los vendedores para que obtengan el nuevo carrito de tamales. «Esperamos poder poner estos carritos en manos de los vendedores sin ningún pago inicial», informa.

Un primer vistazo en el diseño revolucionario del primer carrito «legal» de venta ambulante de tamales en Los Ángeles que costará aproximadamente $7,500

«Cuantos más carritos, mejor. Especialmente si esos carritos van a ayudar a que los vendedores sean legítimos en esta industria», dice Sergio Jiménez, organizador de Community Power Collective, otra organización sin fines de lucro que defiende la venta. «Creo que el costo es muy alto para simplemente mantener la temperatura constante, pero tal vez con fondos de la ciudad y el condado, esos carritos definitivamente podrían usarse».

Para los vendedores que pueden perder miles de dólares cuando el departamento de salud confisca sus carritos, la aprobación es un pequeño vistazo de lo que esperan que suceda. Este año, los vendedores que hablaron con Capital and Main y L.A. TACO dijeron que estaban dispuestos a comprar un carrito aprobado por el departamento de salud siempre y cuando no fuera demasiado grande ni demasiado caro.

Vendedores ambulantes como Juana Domínguez, quien actualmente vende quesadillas y tacos en las calles Main y 41st en Los Ángeles, están abiertos a la idea de comprar un carrito que pase las brutales inspecciones del Departamento de Salud Pública. La vendedora de 52 años empezó a vender en las calles antes de llegar a los Estados Unidos. Comenzó hace 10 años vendiendo dulces y chicles antes de poder pagar un carrito de tacos.

Una representación de un carrito naranja de tamales. Imagen de Richard Gómez de Vahe Enterprises.

Domínguez reconoce la necesidad de un carrito aprobado por el condado. En los últimos años, le han quitado sus carritos tres veces. Cuando perdió el primero, que tenía una combinación de parrilla y refrigerador, le costó a ella y a su esposo $3,800.

«Me da mucho gusto que finalmente haya un carrito porque no ha sido fácil para muchos vendedores», dijo sonriendo, luego de ver una foto del diseño.

Aunque el diseño hecho por Gómez no se aplica a Domínguez como vendedora de tacos, ella está feliz. Dijo que alguna vez también vendió tamales y comprende las dificultades que enfrentan esos vendedores. «Me salía a vender en las fábricas», comenta.

Para mantener calientes sus tamales, que se preparaban en casa, tapaba la olla con plástico y un paño para que el vapor fluyera, y luego sujetaba la olla a una hielera con ruedas. Cuando se le preguntó qué pensaba del precio del carrito de tamales de nuevo diseño, dijo algo similar a lo que dijo en marzo.

«Si viene con los permisos, es genial porque eso hace que el precio del carrito no se vea tan mal, pero si aún necesitamos comprar permisos después de obtener el carrito, puede ser difícil para algunos vendedores», dijo, refiriéndose a los vendedores que se están recuperando de la pandemia. «Pero entendemos que es un paso adelante».

Su principal preocupación era tener que pagar una tarifa mensual o por hora en un comedor: cocinas aprobadas por el Departamento de Salud Pública donde los vendedores pueden preparar la comida antes de salir a venderla. El código de salud estatal exige que una variedad de alimentos, como los tamales, se preparen solo en los comedores. Incluso a los vendedores de frutas no se les permite técnicamente cortar frutas en la calle y solo pueden hacerlo en una cocina autorizada. Según Lyric Kelkar, las tarifas pueden oscilar entre $20 y $32 por hora. Pasar la noche podría costar hasta $200, aproximadamente lo que gana un vendedor en un día de trabajo.

«Mira, eso es algo que hay que tener en cuenta porque es una factura adicional para nosotros. Sin mencionar que no todos los vendedores tienen transporte para ir y venir», dice Domínguez.

Beverly Estrada de At Bev’s Tamales, que vende cerca de University of Southern California, dice que ya está anotada para comprar una de las creaciones de Gómez. «Estoy esperando el mío», dice emocionada.

La vendedora de 42 años vende tamales mexicanos tradicionales, incluidos los tamales de pollo y los tamales de birria acompañados de una taza de consomé (caldo). Ha estado vendiendo por poco más de un año y ya ha recibido advertencias verbales del departamento de salud. Actualmente no tiene permiso y cocina en una olla en casa con una pequeña hornalla y un tanque de propano. Para pedidos grandes, la vendedora sella al vacío los tamales.

«Creo que será una gran oportunidad para los vendedores ambulantes como yo porque, para ser honesta, a veces parece que no tenemos mucho apoyo», comentó Beverly. «El carrito les da a los vendedores un poco de esperanza y ahora está aquí».

Juana Domínguez ya espera que el condado apruebe más diseños.

«Espero que lo próximo sea un carrito de parrilla», agrega.