[dropcap size=big]L[/dropcap]inda Mulvey died homeless. She was 59 when she was found unresponsive in a downtown alley. Donald Ruby died after collapsing on a sidewalk, a five-minute drive from a hospital. And the body of Donald Rickman was found in the driver seat of the car he lived in. He was 70.

They were among the 1,989 people identified by name as having died homeless in Los Angeles County from January 2016 to June 2018, according a list of homeless deaths [downloadable link] investigated by the L.A. County Department of Medical Examiner-Coroner.

Beside each name on the list are such details as their “death date,” “death place,” and “death address.”

On New Year's Eve, about 50 people filled the front rows of the cacophonous nave of the First Unitarian Church in Koreatown to remember people who died unhoused on L.A.’s sidewalks, in its its alleys, encampments, and in cars.

RELATED: Full List of Names from the Homeless Deaths Vigil

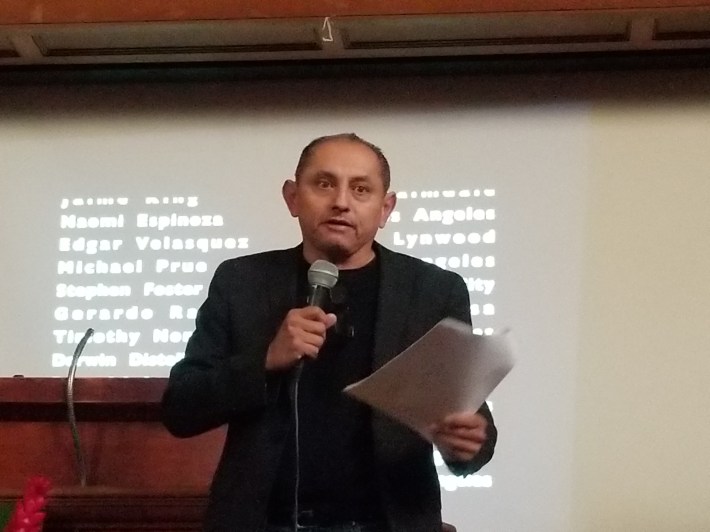

“The dead have names,” said Rene Moya, director of Housing As A Human Right. “Public policy failed them and it continues to fail the tens of thousands of unhoused people, residents of Los Angeles County.”

A modest floral arrangement decorated the church pulpit, flanked by lines of small electric candles placed on the stage. Some of the people in attendance crowded in front, standing to get a better view of a procession of speakers who bore witness to homeless people who succumbed to life on the streets of Los Angeles – hundreds and hundreds of whom are rarely identified.

RELATED: Another Death on the Streets ~ More than 1,200 Homeless People Died in Los Angeles Since 2017

Officially, 720 unhoused people died in 2016, 806 died in 2017, and 463 died in the first half of 2018 — but the actual number could potentially be much higher.

The coroner doesn't investigate every homeless death, said Jill Stewart, executive director of the Coalition To Preserve L.A. “The fact that we were able to get these names is a miracle.”

“I think it is just that we have not hit the importance level for the media yet that these are real people,” Stewart told L.A. Taco. “It’s hard for people to absorb the idea that these are not just ragged losers. There is a whole story behind each one.”

[dropcap size=big]O[/dropcap]ne person likely not on the list was a man called Larry, who was killed in 2016, said Mel Tillekeratne, who leads efforts at the Monday Night Mission and in the #SheDoes Movement, which works to expand shelter services for homeless women.

“He came up to me and said, ‘Mel, I know you always forget, but I want you to remember this: I need pants. My pants size is 32 x 30. I need new pants. Write it down because I know you are going to forget,’ he said.” That was one of the last times Tillekeratne talked to Larry.

Tillekeratne never got a chance to help Larry get a new pair of pants. His body was discovered hunched over on a toilet inside the L.A. Mission. He likely bled to death after he was stabbed in the kidneys, Tillekeratne said. “When you look at these names I want you to picture the people you pass by every day. These are human beings,” he said.

“If we want to change this we have to get angry. That is the only way this is going to change. If we don’t get angry we will be here next year and we will read 1,500 names.”

RELATED: Murdering a Homeless Person Should Be a Hate Crime, City Council Says