Edward Landler & Brad Byer, makers of the documentary "I Build The Tower" about Simon Rodia and the Watts Towers of Watts, Los Angeles. Photo by Gail Brown.

TACO: It took Simon Rodia 33 years to build the Watts Towers. You've been working on "I Build the Tower" for at least fifteen years, what has taken you so long?

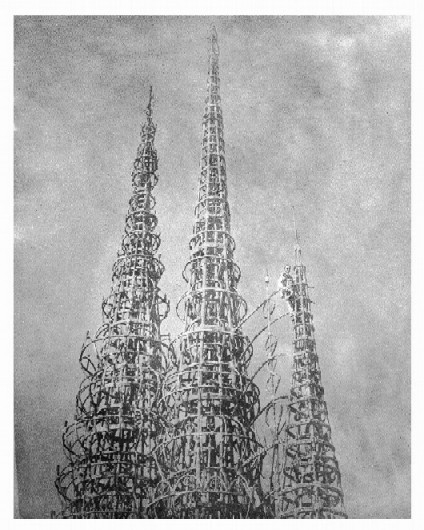

Edward Landler: Los Angeles still doesn't know how to appreciate the Watts Towers. One problem with viewing the Watts Towers as a work of art is that the man who built them didn't have a pedigree. I think it's one of the greatest works of art of the 20th century but we live in a city and a culture dominated by an industry that is mainly concerned with the bottom line: how much money did you make? Sam Rodia, the man who built the Towers, didn't come from a school or studio, he was just a guy. How's it going to make money? Who's going to buy them?

The problem with getting the proper respect from the city is the Towers are in the wrong part of town. People don't want to go there. They're afraid. But they're afraid of a myth. There are plenty of other areas of town which are just as dangerous as Watts but Watts has the history and aura of violence and gangs. There are parts of the valley with higher incomes and similar problems.

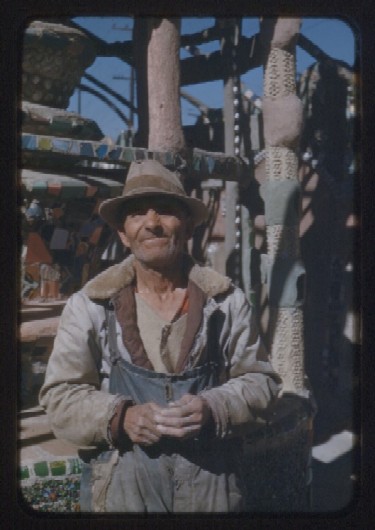

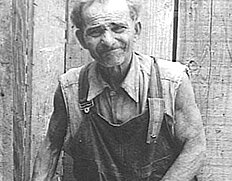

Rodia, building the third tower to the right.

Taco: I did a search on the internet and didn't find a lot of local websites about the Towers.

EL: The Friends of the Watts Towers Arts Center have a basic information website (www.wattstowers.org) but it isn't completely worked out yet. The film's website wwww.ibuildthetower.com gives real information about the Towers and Rodia.

The City's Department of Cultural Affairs website doesn't really make mention of the Towers. They consistently seem to ignore and undermine the work of the Watts Towers Arts Center. They spent years doing conservation on the towers. We talk a little about the restoration work in the film. In 2003, after almost 30 years of the city's conservation efforts, an independent inspector said that the city should develop a long-range conservation effort because it's never been done. What were they doing for 30 years? They didn't develop a long-range plan because of a short-sighted bureaucracy and because they treat the Towers with the same kind of benign neglect you see in South LA or East LA as whole. The town is controlled by financial interests and developers for whom anything east of La Cienega and South of Wilshire doesn't exist, because they can't make money there.

Now you have this new revitalizing of Downtown going on. Developers are going to make scads of money, but I don't know that it's going to make Los Angeles a more cohesive city. It's going to help the economy of Los Angeles in terms of its richest people.

This may be part of the reason why it took so long to make the film - which is just as well because part of the archival material in the film only appeared during the last year of work on the film.

Rodia at home with the Towers, 1953. Photo by Jay Weynn.

TACO: How did you find it?

EL: We were showing part of our rough cut at a fundraiser at the Italian Cultural Institute in Westwood. While I was over there preparing for it, somebody called and said he had to talk to one of the producers. He said, "I can't be there tonight but I have something. I don't know if it's any good but I want to give it to you. I haven't looked at it in 20 years. It might be dust. In the early 50's I was a friend of Sam's and I have 10 minutes of 16mm footage of Sam at the Towers."

There was some color footage of Sam at the towers which we had from a documentary made by a USC film student as a 10-minute film, which had been shown all over the place. In it you can see Sam isn't comfortable because it's just some student imposing himself on Sam and the towers. But when I saw this other black and white footage, my jaw dropped. Sam was enjoying himself because he liked the guy, they were friends. It's just some wonderful footage. When I saw that I realized, "Oh, we finished the film." We needed one visual thing to hold it together and within a year after getting that footage, the movie was done.

TACO: How did you first connect with the Watts community?

EL: In the mid seventies, I came back to Los Angeles. I grew up here. I left to go to college and a whole lot of places and I came back in 1975. For a while I worked with a Boys & Girls Club in South Central Los Angeles. I taught photography, drama, stuff like that. Two or three years after that, I got involved in Watts. I was working as a waiter and one of the customers was a developer developing an industrial park in Watts, and I told him about my filmmaking background. He said he needed documentation of what was going on and he invited me to a community meeting in Watts. Instead of getting involved with the industrial park, I got involved with the development of a food co-op. That's when I met John Outterbridge who was the director of the Watts Towers Art Center, and I started hanging out at the Towers.

John Outterbridge working on Third Eye Dreaming, his own interpretation of the Watts Towers. Click here for more info.

EL: In the sixties, I had gone to Yale and was a part of a special 5-year BA program funded by the Carnegie Foundation that allowed its fellows to take a full year out of our studies to work in a non-Western culture. I wound up in Calcutta working for the Ecumenial Urban Institute, which was an offshoot of the Global Board of Methodist Ministries. I was a Methodist missionary... a Jewish one... the only one ever, it seems. I was documenting the work of social services organizations in Calcutta and writing documentary films about them. That's when I met the film director Satyajit Ray and he took me under his wing. I had a 16mm Bolex camera and I shot a great deal of footage in Calcutta, always with the intention of also shooting some city in America and interweaving footage of the two cultures to get a sense of what's common in human cultures no matter what the local cultural differences are.

During the time I started working in Watts, I shot 16mm footage all over LA using the Watts Towers as a metaphor. So I completed the short film I had started in India, a 13-minute piece called "Pharaoh's Dream." Right around the time I finished it, I was introduced to Brad Byer through John Outterbridge. Brad had done all this research on his uncle's life and he wanted to make a movie out of it, but he didn't know how to put it together. He had talked to other filmmakers about it, but after we talked, he figured the way I saw it was close to the way he saw it. He brought the Rodia family connection, I brought the Watts connection.

LA Community Anti-Smoking Mural, "Ceremony for smokers" by Elliot Pinkney, Watts Towers Arts Center.

TACO: When you say you were hanging out at the Towers, did you do something specific over there?

EL: Not really. The Arts Center was there. I was on the Board of the Food Co-op for a while so I was involved in it until it opened. The short film was made in commemoration of the opening of the Food Co-op. To survive at that time, I was doing production work as a location scout and production manager. Around that time, I was also on the founding board of the IFP (Independent Feature Project) in Los Angeles. Now it's called FIND (Film Independent). It's still a valuable organization.

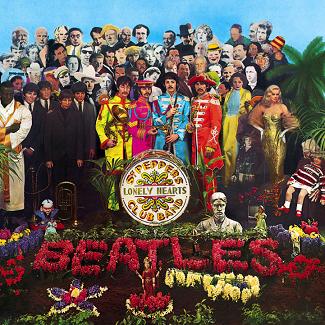

Simon Rodia top right next to Bob Dylan.

Getting back to 1982 when I met Brad... we didn't have any money but we got the opportunity to do an interview with R. Buckminster Fuller, one of the major genuises of the 20th century. He had become famous in the sixties - especially after his book, "Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth." He was a futurist, an architect, a designer, a real Renaissance man... He was a structural genius and invented the geodesic dome.

He consented to do an interview in which he would analyze the structures of the Towers. He loved the Towers. He thought this was one of the great works of architectural sculpture of the 20th century. In the interview, Fuller explains how the Towers hold together and why the Towers are an engineering marvel, why they are so stable. It's one of the most stable structures on the face of the earth, yet it stands in a foundation only 14 inches... a fourteen-inch foundation for a structure the height of a 10-story building. He said Rodia figured this out all on his own and if he had been educated this would have been educated right out of him.

I thought it would take 5 to 6 years to complete the film but it took that amount of time just to raise the first $100,000. Everybody was saying the Towers were wonderful but nobody wanted to give us money until we got a $50,000.00 grant from the National Endowment for the Arts and $20,000.00 from Olivetti in Italy. Nobody in LA would give us money until the money came from outside of LA.

TACO: Who did you go to in LA?

EL: Everybody.

TACO: What about the Getty?

EL: At that time Getty had a film division based in New York. They said they don't make movies about any kind of art if it's post-1900. Getty's attitude was "How do we know it's art until it has a stamp of approval." I think that attitude is also reflected in why the Getty Trust built the museum up on a hill instead of downtown. They didn't want to mix with the people. They say, "We let the children come from the schools," but I don't think they pay for that. It's a highly elitist organization and that's what LA is.

The actor Vincent Price, bless his heart, gave his art collection to East LA College. He had a wonderful collection of Impressionist and Post Impressionist and Modernist work and it's at the East Los Angeles College Vincent Price Art Gallery. Why aren't more people aware of this?

R. Buckminster Fuller aka Bucky with geodesic dome. Source: www.bfi.org.

TACO: Was the $100,000.00 enough?

EL: All together we wound up spending about $250,000.00. By 1990 we had raised the first $100,000. That's when we started shooting interviews of people and the towers. We had enough money to do all the principal photography, here and in Italy. We shot in Southern Italy where Rodia was born. We ran out of money right after finishing principal photography in 1995. That's when I started going into deep hock putting together a rough cut over the next two years. Then about every 6 months or so, we'd do fundraisers - raising $10,000 at one screening, $5,000 at another, $25,000. We still had to go into hock to fully complete post-production, a process that took about five years.

TACO: Did you exhaust all the possible grant sources?

EL: Oh yeah. We did a fundraiser way back in 1989 after we got the Olivetti and NEA funding. All sorts of rich people let us use their recognizable names on the honorary committee, but when I asked them for money they said, "Our names are good enough to get you money so you don't need money from us." I went back to them more than ten years later and then some came up with something, because they thought we'd actually finish, I guess.

On the other hand, we received financial help from a wonderful couple in Santa Barbara, strong supporters of the arts, the Lovelaces. Lloyd Rigler, one of the inventors of Adolf's Meat Tenderizer, donated money before he died. A local businesman named Alan Sieroty was also a consistent contributor.

And, in some ways, even more importantly as a reflection of the power of Rodia's work, more than a hundred people from all walks of life made individual contributions of sums under a thousand dollars and in-kind services.

I learned a lot about the way this city works through all this and we're having just as hard a time having it distributed.

TACO: Where are you at in the process?

EL: I've almost reached the point that I don't want to go to distributors. In a way you have to wait for someone who's interested to come to you. 15 and 20 years ago it would have been different, because distributors involved in documentaries realized it takes time to develop a marketing approach to get it out there. Now if it's not sensationalistic, if it's not about something immediate, if there are no gang shootings, they don't know how to market it. But our film is timeless. It is just as valid today as it will be 15 years from now because it's universal. Most documentaries don't stand the test of time.

TACO: Yours is not a traditional documentary, it is very poetic.

EL: Perhaps it's traditional in terms of what documentaries were 30 years ago.

TACO: I know you've been part of a few festivals.

EL: It premiered at the Pan African Festival here in LA and it's screened at some quirky festivals internationally like Leeds in England and a couple in Italy. It got wonderful reviews at the International Festival of Films on Art in Montreal where one reviewer said it was the best film of the festival. It's been shown at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.. and at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City.

TACO: Were you part of the massive LA Exhibition at the Centre Pompidou in Paris?

EL: We were supposed to but then they said it didn't fit the time period they were covering, that is after 1965.

It is hard to deal with art that comes from an unexpected place. Most outsider art is naive and curious and fun but not particularly deep and interesting. Rodia's towers are deep and profound. There are a handful of so-called outsider artists that touch you at a deeper level and Rodia is one of them, he stands apart.

Le Palais Royal du Facteur Cheval. Source: click here.

TACO: Who are they?

EL: Somebody made a movie a couple of years ago about a guy who lived alone in Chicago and when he died they found piles of drawings and paintings of magical figures, his name was Henry Darger. The film got some attention because the filmmaker was established. In France you have the Palais Royal of le Facteur Cheval. That's kind of interesting work, but he wasn't an engineering genius like Rodia. He carved out massive Babylonian-style structures. In Chandigarh, India, the rock gardens of Nek Chand are remarkably whimsical and imaginative.

TACO: Where would you like the film to go?

EL: I would love for the film to have theatrical distribution. But that depends on having a distributor who is willing to make that gamble. I think the film could find an audience. The DVD distribution is where we are going to make the most money.

TACO: Are the LA schools buying it? If I had kids to send to school, that's the kind of story I would like them to learn.

EL: The schools have to find out about it first. I haven't approached LAUSD yet. I'm not sure how that works. Right now I'm starting with the libraries. A good many stills from the film came from the Central Library and the person who helped me there thinks it is a great film so she is passing word of it down to acquisition to get it picked up by the library system. It should be in every library in the country. Once again it will take time but museums, arts institutions, schools, libraries throughouts the world should have it. It will have a long shelf life.

TACO: When you talk about LA being an industry town, Hollywood loves stories of triumph over adversity. And America and California have the reputation of being the place where anybody can succeed, regardless of their background. I've never been asked "Where did you go to school?" It's so liberating. But Rodia is not traditional. He just left Watts one day and went to Martinez. The Towers didn't make him rich and famous and that's not why he built them.

EL: He was still a broken-accented guy who had abandoned his family.

TACO: What did the Towers mean to him after he left?

EL: He was finished. Like he said in an interview: "Why I do it I don't know. Why the man makes the pants? Why the man makes the shoes?" I don't want to supply the answer. I want people watching the film to supply their own answers.

TACO: Most industry films don't leave much to the imagination.

EL: That's why America is in cultural crisis today because there is no single answer. Life is not as simple as that. Works of art present a picture of the world which you have to explain for yourself. All the evidence you need is up there, the connections, you have to strive to explain the connections yourself in terms of your own life and experience. All the films with answers like "and that's the way it is, folks" these movies don't last. They don't have a great deal of depth to them. What happens to the tramp and the flower girl at the end of "City Lights"? There are great American indigenous filmmakers: Preston Sturges, Buster Keaton, Stanley Kubrick. But they got their work done despite the industry rather than because of it.

TACO: Have you screened the film in Watts?

EL: There are no theaters in Watts. We showed the rough cut years ago as a fundraiser at the Watts Towers Arts Center. We should show the completed film there. I need to talk to Rosie Lee Hooks, the current director of the Arts Center about that.

TACO: Do you still have the same connections in Watts?

EL: I'm still very much involved in the Towers. I was just there at a meeting yesterday morning. There's a lot going on as to how the Towers should be taken care of.

TACO: The Towers are in the hands of the Cultural Affairs Department?

EL: By contract with the owners of the Towers since 1958 - the Committee for Simon Rodia's Towers in Watts - the Watts Towers were given to the State of California and the State has entrusted their care of the City of Los Angeles. The Committee is very upset with how the Towers have been taken care of and there's a constant battle to get attention. They managed in the late 1970's to act to get the conservation started and then they had to file a lawsuit which was upheld in Court so that the City had to improve the way it was doing the conservation. Their methods are still a matter of dispute.

TACO: Do you address this in the film?

EL: We boiled the controversy down to about three minutes in the film.

TACO: What would you like to see happen?

EL: Gradually, we are selling it on DVD on the internet, and I hope for a theatrical distribution one day and TV after that.

TACO: To get them in video stores, do you need theatrical distribution?

EL: Not necessarily. Two years ago, "Idiocracy" got not release and now is doing quite well on home video. It's a word of mouth process.

Los Angeles should embrace the Towers, fully support the Arts Center, restore adequate parking and build appropriate facilities to welcome people to see the Towers. They should be publicizing the Towers as one of the greatest works of art of the 20th century and the single greatest work of art that was ever made in Los Angeles... with the possible exception of Charlie Chaplin's "City Lights"... certainly LA's greatest work of architectural sculpture.

I have no regrets about the amount of time spent on the film because it's an important story. What the film is about is the nature of art itself. Why do we make things? Who do we create? What is art for? Rodia couldn't talk about it, he didn't think about those things but he showed it in his work. In the Towers we see the redemption of the spirit... humanity striking off its chains and rising to the heavens. No wonder it has become a symbol for the Watts community. In the 1965 riots, a couple of blocks away, businesses were burnt to the ground on 103rd Street, but nobody touched the Towers. The Towers were saying, "Hey, we want to be free."

TACO: Does the new generation look at it the same way?

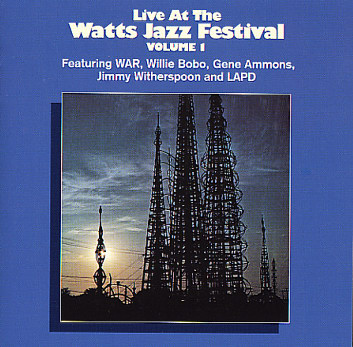

EL: Not as much because the Towers, through the 80's and 90's were cut away from the community with a fence around them and the scaffolding up. Since 1976, the Watts Towers Jazz Festival has gone on every year. During the 80's the festival was tremendously popular, crowded with people. After the 1992 riots, John Outterbridge was forced to retire as director of the Arts Center and, though the festival has kept on, it has had a lower profile because the city severely cut the publicity. Here is another instance where the Towers, as noted by Los Angeles historian Mike Davis, are a symbol of the neglect of South and East LA.

TACO: The only thing that bothered me about your website is that the last thing mentioned about Watts is its deterioration into a ghetto after World War II. It doesn't create an incentive for people to want to go there.

EL: Because if more people go there to see a great work of art, more possibilities will arise to develop the area. But the City itself discourages people from going there. The Cultural Affairs Department kept scaffolding on the Towers for more than twenty years. They reopened the Towers in 2001 and they made a big deal about it. That was it. Over the past three years, they tore up the parking lot to build a larger building for the Arts Center, but the budget for the Arts Center has been slashed so they're cutting down the programming in the existing building. But there is no designated place anymore for people to park if they want to visit the Towers.

Something might be shifting now. We don't know yet. It's just that it's an area of poverty and deprivation and that's why the Towers are there. You see a visual metaphor for human aspiration growing out of that area. That all this heavy steel and concrete can rise so lightly into the sky, no wonder when people come see it, they are affected. There is something powerful there.

"I build the Tower" is available for purchase at www.ibuildthetower.com. Look for the upcoming review of the film on Taco.

One of Simon Rodia's many signatures forever engraved in the Towers. Photo by Floyd B. Bariscale found on flickr.com.