The origins of radical food in Los Angeles

[dropcap size=big]W[/dropcap]hen Jonathan Gold named Locol the LA Times “restaurant of the year,” he emphasized its commitment to serving the people of Watts, where it is located. It offers them inexpensive-but-healthy food as well as job opportunities in an environment that is as hip and multicultural as Los Angeles itself. Gold lauded Daniel Patterson and local hero Roy Choi, the two culinary luminaries who started the restaurant, for their sense of social purpose and commitment to changing the landscape.

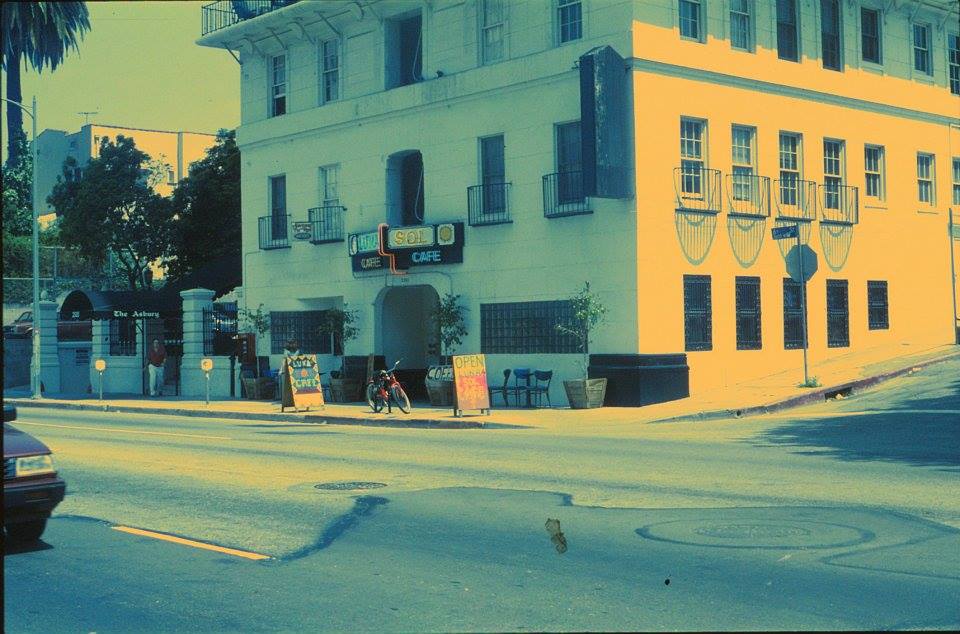

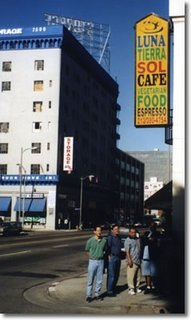

What Gold did not say is that Los Angeles has a long and fascinating history of socially engaged eateries and that some of them are far more radical than Locol. Consider the Luna Sol Café, which operated near MacArthur Park from 1996 to 2003. It provided low-cost, nutritious fare and had deep roots in the multi-ethnic, underground scene of its time, but, crucially, it was a worker-owned cooperative, in which responsibilities and privileges were shared in a horizontal, egalitarian way. It is the only restaurant of this type that LA has known and one of very few in California's history.

From Occupation to Full-Blown Restaurant

Luna Sol emerged at a moment when the credibility of the city’s establishment had reached new lows, and many felt that it was necessary to rebuild society from the ground up. Everyone had seen LA’s Black and Brown masses turn the world upside down during the 1992 rebellion, forcing themselves into the discussion, and many had watched with frustration as politicians responded to this with bogus promises, plans, and programs. There was sort of a running battle between the old guard and the newly energized forces of change. For example, the LA Conservation Corps ran a youth-oriented jobs program that treated the kids like cattle; in response, the youth seized the program’s building in 1995 and transformed it into an activist hub known as the Peace and Justice Center.

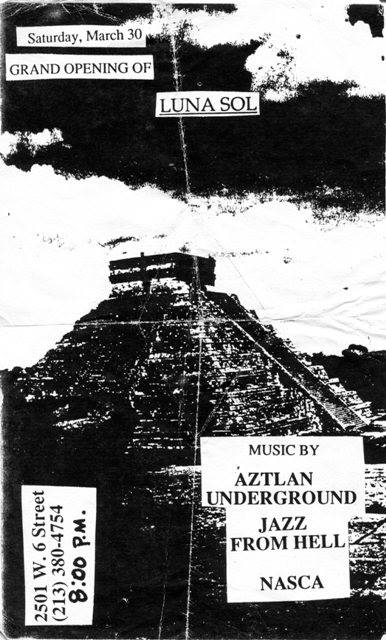

Some of Luna Sol’s founders participated in that occupation. When it ended in 1996, they reorganized immediately. They started a collective home in West Adams in the “Marvin Gaye House”—where Gaye had been murdered by his father in 1984—and rented a storefront with a beat up stove and an old refrigerator at 2501 West 6th Street, which soon became the Luna Sol Café. The initial crew knew that they wanted to build a community space, and to do something with food, but they did not anticipate the magnitude of the experiment that they were about to undertake. “We never imagined that we would be running a full-blown restaurant,” Tito Lopez, an original member, told me recently.

A workers’ cooperative from the outset, Luna Sol had no bosses or managers but rather a flexible structure built around levels of involvement. There were core members, who made big decisions and frequently worked fifty to sixty hours per week. They received an $800 monthly salary, which was practically nothing, even back then, “but we knew how to get by,” said Lopez. There were also employees, who received an hourly wage and could become core members if they wished. Finally, there was an evolving and much-appreciated network of volunteers. During its prime, the restaurant had six core members, eight employees, and two or three volunteers. The crew was Black, Latino, Asian, and white; most were in their twenties and teens. It became Luna Tierra Sol in 1997.

Food, Community, and Gentrification

The menu contained a full selection of breakfast, lunch, and dinner items as well as a “Mission Statement” explaining that their food was part of a broader effort to encourage community. The fare was mostly Mexican, although Luna Sol was never a Mexican restaurant per se, and they did not serve meat—it was among a handful of vegetarian restaurants in LA at the time. Dish names often signaled the project’s radical spirit. For example, there was the Xipotle Bowl, which was a big favorite—substituting an X for the CH in chipotle was a Chicano movement practice intended to highlight Mexican American’s Aztec roots and the loss of identity caused by colonization (a la Malcolm X). There was a punk reference with the much-loved Rude Girl Fries; they were a riff on chili fries, offered with home-made red sauce and cheese. And there was a nod to the counterculture with the Chimi Hendrix plate—tofu grilled with chipotle packed into a giant tortilla with lettuce and cheese. And hip-hop was present in the Freestyle Wrap. The restaurant was open from 7:00 AM to 10:00 PM daily. Luna Sol also earned crucial income by catering for local nonprofits two-to-three times a month.

Full of mismatched furniture and with brightly painted walls, it was a node in the city’s large and amorphous radical scene. Issys Amaya, who was just fifteen when she got involved, explained to me that it was a “safe and comfortable place to organize, create, and network.” People often gathered there to unwind after protests, or to plan new ones, and it was a key destination for out-of-town activists. The restaurant also held regular open-mic nights, art shows, musical and dance performances, and even yoga classes. Most of the performers were enthusiastic amateurs, but some big names made an appearance too, such as Manu Chao, Dilated Peoples, Saul Williams, and Fredo Ortiz, the long-time Beastie Boys drummer.

Things peaked in 2000, when the Democratic Party held its national convention in Los Angeles. The constant protests and vibrant, oppositional arts and music scene made the establishment’s grip on the city seem especially fragile. Obi Iwuoma, another founder, told me that “it was a charged time,” and that many previously apolitical types had been “pulled into the tide.” Luna Sol thrived in the tumult—there were even discussions about opening a second location. However, government repression following 9/11 changed everything. Activists scattered, and catering jobs dried up. The rapid spread of the Internet also seemed to make sustaining such community spaces less urgent. Gentrification had an impact too—the Luna Sol building changed hands and the new owners would not offer a viable lease, a story all too familiar to people of color in Los Angeles.

The Last Meal... And the Next?

When Luna Sol served its last meal in 2003, an important chapter in the local history of radical food projects came to a close. As a cooperative, Luna Sola eliminated the exploitative relationship between bosses and workers, a pillar of capitalism, and, in this sense, it declared that good food and capitalism don’t mix. Locol, by contrast, focuses on reconnecting marginalized people to the capitalist system by selling then quality products and providing work experience. Both restaurants had (or have) a social mission, but one was anti-capitalist, the other works within the existing system.

What is the relationship between these two ventures? One could say that Luna Sol’s radicalism reflected the youthful exuberance of those involved and that Locol corrects this with its more “realistic” acceptance of capitalism's strictures. Luna Sol’s collapse seems to support the argument that it was too idealistic, too political to survive in a city that is often opposed to radical change. On the other hand, Locol is losing money in Watts and its Oakland branch just closed, so maybe Locol’s founders are also running into similar economic realities, even as they play by the rules. Maybe they are naïve to think that one can use capitalist tools to deliver good food to the underprivileged and excluded; perhaps Luna Sol will have the most to offer subsequent generations of radical restaurateurs.

At the very least, these questions indicate that LA’s restaurant history is more complicated than we normally acknowledge, which we should bear in mind as we consider future possibilities. Both Luna Tierra Sol and Locol show that there is a hunger for new models, new modes, and something different. What will the next radical reinterpretation of the L.A. restaurant look like?