[dropcap size=big]L[/dropcap]OS ANGELES – Demetra Johnson is moved by the recent Black Lives Matter protests across the country, because for so long the fight against police brutality has been weathered by Black and Brown people.

A mural of her son looks out onto Vermont Avenue from her small grocery store in South Central.

Demetra’s 16-year-old son Anthony “AJ” Weber was shot and killed by Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Deputies on February 4, 2018 about a mile from their home.

He was a new father when he was shot 16 times by two deputies who said he had a gun tucked into his waistband. Officers say he reached for his hip when they shot him, but no gun was recovered at the scene.

Since then Demetra has found her voice as an advocate on police accountability.

It hasn’t been easy.

AJ’s family sued the Sheriff’s department for documents on the shooting investigation, but Demetra says from the 700 pages of reports they received most of the investigation revolved around whether AJ had any gang affiliation and if he could get access to a gun. An anonymous 911 caller said a Black man pointed a gun at a passing car in the Westmont neighborhood where deputies killed AJ.

“The officer who chased down AJ doesn’t know him. The 911 call that they got basically convicted and executed my son,” Demetra tells L.A. Taco Then newly elected Sheriff Alex Villanueva told L.A. Taco in November 2018 that his department would not “demonize or cast aspersions on the individuals” who are shot by police.

“That seems like a very shallow ploy at trying to defend the organization by shading the individuals involved, calling them a gang member or this or that,” said Villanueva. “We’re just going to take the facts. We are going to be as transparent as possible.”

“They took away something so precious from me and they gave me so much power. Every time they murder someone they give another family that power.”

Demetra says, “It was a lie. It was a complete lie that he was going to be transparent. It’s been two years since AJ was killed and we just got those reports. Other than the officer’s original statement there was no investigation into that officer.”

In a recent interview with L.A. Taco, Villanueva says he stands by his previous comments and he will wait to comment after an investigation from the District Attorney’s Office on the officer’s actions is concluded. Weber was a young man shot in the back multiple times and Villanueva says the shooting took place before his time in office.

But 18-year-old Andres Guardado, killed June 18, 2020 was on his watch. Villanueva spoke to L.A. Taco hours before a caravan of criminal justice advocates drove to the Hall of Justice in downtown L.A. to ask for the Sheriff’s resignation over his office’s handling of the Guardado case, which happened less than a month after George Floyd’s murder.

Speaking generally on officer-involved shootings he said, “These situations are very dynamic. I guarantee you the deputies involved in both cases, the Weber and Guardado case, didn’t wake up realizing that their lives were going to be turned upside down. We’re putting deputies in conditions that are hazardous by their very nature and then when you add reports of people armed with weapons into the mix, that rate raises the level of concern.”

On August 30th, reporter Kate Cagle tweeted a video of a deposition by LASD whistleblower Deputy Art Gonzalez, who said under oath that the officer who shot and killed Guardado was a prospective member of the Executioners, an alleged violent clique of tattooed deputies inside the Compton Sheriff's station.

On August 30th, reporter Kate Cagle tweeted a video of a deposition by LASD whistleblower Deputy Art Gonzalez, who said under oath that the officer who shot and killed Guardado was a prospective member of the Executioners, an alleged violent clique of tattooed deputies inside the Compton Sheriff's station.

“There’s no easy solution. Policing done by human beings is never going to be perfect. It’s going to be a lot of perception in what a lot of people see from their perspective. It varies from person to person,” Villanueva told L.A.Taco before Gonzalez' deposition became public. “What may look like a good shooting from one person’s eyes may look like an execution. That’s the wide gamut of opinions that can be out there.”

(The Sheriff’s Department published the shooting investigation into AJ’s death seven days after L.A. Taco filed a California Public Records Request.)

Outrage over police brutality finally spilled out into the streets this summer and yet, Demetra says she couldn’t march in the recent Black Lives Matter protests because she caught COVID-19.

On May 28, 2020 roughly 20 LAPD officers raided Demetra’s home. None of the officers wore face masks and no one immediately provided her with a warrant when they entered her yard and demanded that everyone in the home step outside.

According to a complaint filed on behalf of the family by the American Civil Liberties Union, LAPD officers said they were looking for a suspect with a gun. A video shared by the family with Black Lives Matter, Los Angeles shows multiple officers at the family’s home in South Central.

Demetra’s mother, who is in hospice care, remained in her bed during the search. Demetra says she also caught the virus. Earlier this year, the California Attorney General’s Office cut-off the LAPD’s access to the controversial CalGang database, because several officers falsified field reports.

Demetra criticized the program at a May 5, 2020 police commission meeting, where she said her other son who did not have any interaction with police was placed into the CalGang database. Still, police forced her family into their yard later that month and claimed they were looking for a suspect. “They’re supposed to be looking for a person but they’re tearing up our house,” says Demetra. “You would have thought they were the ones who killed my son.”

A month after AJ was killed Demetra was still in a daze. A headache dogged her and details from that time were fuzzy. She found herself sitting in her car outside her home, waiting to take her other two sons for a haircut. When they stepped outside, she gasped.

“They were wearing black shirts and blue jeans,” Demetra says. “That’s what AJ was wearing when he was killed.”

Mely Forever

Melyda Corado, or Mely as she was known to friends and family, was working at the Silver Lake Trader Joe’s on July 21, 2018 when she heard a car crash outside. Without hesitation she ran to the front of the store to see if anyone needed help.

As she approached the door Mely was hit by an LAPD officer’s bullet. She bled out in the store surrounded by coworkers and strangers.

Police claimed they were under fire and shooting at Gene Atkins, a man who led police on a high-speed pursuit that ended on Hyperion Avenue in front of the grocery store. Earlier in the day he shot his grandmother and girlfriend. Both survived and while it was an officer’s bullet that killed Mely, Gene Atkins was charged with her murder.

Albert Corado Jr., Mely’s brother, has become a staunch advocate for not only defunding the police, but dismantling the LAPD. He’s an organizer with multiple groups that seek to cancel L.A.’s hosting duties for the 2028 Olympics (NOlympics) and he’s led protests outside Mayor Eric Garcetti’s home during the pandemic on rent control (the People’s City Council, which he co-founded during the pandemic) and has helped raise money for community aid programs.

There’s a radical sense of urgency that drives Albert and he describes it like an obligation to his sister, but also to show others that you don’t need a tragedy to motivate you. “She was my barometer on if what I was doing was out of line. And so OK, I think is what I’m doing worthwhile? Am I being a good enough person?” Albert asks himself.

It’s the unspoken promise a person makes to the ones they love and to Albert that could mean spending the rest of his life trying to make sure that no one forgets Mely. “I make sure that I take the fight to the ones who did this to her,” Albert says. Officers Sinlen Tse and Sarah Winans fired eight rounds toward the front of the Trader Joe’s grocery store on an otherwise quiet Saturday afternoon.

LAPD officers shot and killed Mely, a Latinx woman in the affluent Silver Lake neighborhood while she was at work, because officers were trying to shoot a Black man. All those actions were found to be within the department’s policy according to the L.A. Board of Police Commissioners.

Albert and his father sued the city of LA for documents pertaining to Mely’s death, including her autopsy which had a security hold placed on it. (The LAPD declined to comment on the investigation into Mely’s death because of the pending litigation.)

Grief, Albert says, works in different ways. Albert found his community through volunteer work, but he also feels energized to see the Black Lives Matter protests take off nationwide, with more people demanding a diversion of city budgets away from police and into essential services, like housing or mental health outreach.

“Everything is being questioned now. It’s incredible and fills me with hope to see so many people marching for BLM and other important issues. Mely is gone and that’s always going to hurt, but I’m going to make sure that Chief Michel Moore doesn’t have a job,” says Albert.

“For those of us who are just showing up, it’s our duty to keep showing up.”

“What we have on our side is the spirit of our ancestors who have been killed by the police. The LAPD has the ghost of those people haunting them.”

At the second anniversary of his daughter’s murder Albert Corado Sr. said, “There is a difference between Mely and other victims. Mely wasn’t resisting arrest. Mely wasn’t fighting the police. Mely wasn’t being chased. Mely was not passing a $20 bill. She was at work. That is the difference. Therefore, we demand justice for Mely. She was a victim. Not a suspect when she was killed.”

The Corado family invited L.A. City Council candidate Nithya Raman to speak at the memorial march and she summarized why the families who have lost loved ones to police violence are in a unique position at this time.

“Our Black leaders, all of our front-line organizations that built this movement and people like Albert who have joined the fight, they knew long before these protests what was wrong and what needed to be done. When we were all finally ready to show up they welcomed us into that fight,” said Raman. “For those of us who are just showing up, it’s our duty to keep showing up.”

Grechario

When Grechario Mack was 10 he pushed his little sister out of the way from a moving water truck. He was hit and knocked down. But he got back up.

His family called him a hero.

He was a gifted student, but his dad sometimes had to sit with him in class when he acted up. Grechario loved to go fishing but did not like to eat fish.

He had two daughters and at 30 while he was having a mental breakdown, he was shot several times by the LAPD at the Baldwin Hills Crenshaw Mall on April 10, 2018.

He got back up. He was shot again. He got back up.

Officers shot him two more times as he laid on the floor.

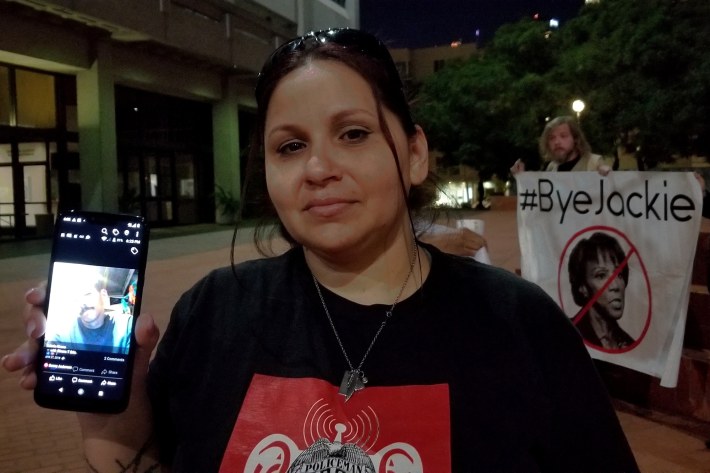

A common goal for all the family members and community activists is to remove Jackie Lacey from office. All the interviewed families for this story said they would vote her out of office this November.

Quintus Moore watched his son run for his life on the morning news, the day after Grechario was killed. Video footage showed a man running from the police with his face blurred, shots ringing out in the crowded mall.

“I heard that there was a killing at the mall as I was getting ready for work. I thought, oh that’s our mall and that’s fucked up with the way they shot up the businesses to kill this man,” says Moore, not realizing it was his son. “As I’m on my way to work, I’m getting nervous and thinking, I’m hoping that it’s not our Grechario.”

According to police records, a mall security guard told Grechario he had to leave the mall because he had a kitchen knife. Grechario asked if the guard could call for a psychiatrist because he was paranoid.

Instead, police received reports of a Black man with a knife acting erratically.

“He had just come out of incarceration and he was taking some type of psych meds,” says Quintus. “But police are always going to kill Black people when they have a chance. A white man had a machete in Pacoima not too long after Grechario was killed. That white man was surrounded and taken into custody, no problem.”

Then police chief Charlie Beck said a bean bag rifle should have been deployed, but it arrived too late on the scene. Instead, Officers Ryan Lee and Martin Robles arrived with their guns drawn and Grechario ran. LAPD Chief Michel Moore said the officers followed department policy, but on March 19, 2019, the L.A. Police Commission found that the last two shots fired were out of policy.

Quintus was in the dark for several hours after Grechario was killed, but on the day of the police commission meeting he memorized all the gruesome details of an independent autopsy report that said his son was shot seven to eight times, including in the back and those first shots were non-life-threatening.

The officers involved in the shooting have not been criminally prosecuted by the DA’s office. (The LAPD declined requests for an interview about departmental policies that have been adopted since Grechario’s death.)

In 2013, after George Zimmerman was acquitted in the shooting death of Treyvon Martin, Quintus went to Leimert Park because one of his sons was 17 at the same time and looked like Treyvon. The idea of a Black boy being killed like that scared him.

Now, Quintus finds himself at Black Lives Matter rallies talking about Grechario and the fight to hold police accountable.

“God bless George Floyd’s soul,” says Quintus. “He was the sacrificial lamb to wake up the world. Colin Kaepernick was ignored. When it comes to police brutality, well it’s downright arcane that police officers who kill are not prosecuted, charged.”

The last time Grechario and Quintus spoke was several hours before he was killed.

“I asked him if he wanted to get any fish, but he said no. So, I said, ‘OK well, I love you’ because that’s what I tell all my kids and family,” says Quintus. “He said, ‘I love you too, dad. See you later.’”

“My baby, Eric”

Valerie Rivera has openly cried for her son at police commissioner meetings, at rallies to defund the police and in front of the Hall of Justice in downtown LA, where families and friends whose loved ones were killed by police hold a weekly vigil with Black Lives Matter, Los Angeles.

“Showing the world what these cops did to my son, explaining all of that is my job,” says Valerie. “After I speak and share my story people come up to me and tell me that what they hear breaks their heart. That’s when I know I’m doing the right work.”

Twenty-year-old Eric Rivera died while holding a green squirt gun.

In the sobering light of day, the toy gun’s transparent body is clear with black trim, but on the evening of June 6, 2017, LAPD officers received reports of a man with a gun in the Wilmington neighborhood.

They approached Eric in their cruiser, yelled for him to drop the gun, and shot him seven times. The whole exchange was so abrupt that police forgot to put their car in park and it rolled forward, pinning Eric’s body to the ground.

LAPD Officers Arturo Urrutia and Daniel Ramirez were found to have acted within department policy, even though their cruiser’s dashcam was not turned on or when Arturo Urrutia said he was shot but actually only fell down or the fact that their cruiser had to be lifted off Eric’s body with a fire department hoist.

A 16-page report from the DA’s office says the officers used “reasonable force in self-defense and defense of others” and the investigation into their actions was closed.

Mothers like Valerie or Demetra, brothers like Albert and fathers like Quintus speak about their experiences and they share all the details of their loved ones murders. They have committed to memory all the details, because each of them feel they have to share what happened, because to speak about their tragedies gives life to them.

The Black Lives Matter movement may have allowed millions to march in solidarity with victims of police violence, but Valerie would walk alone if she had to.

“I’m out here for my baby, Eric. We’re the real driving force because of our loved ones who were killed,” says Valerie. “They took away something so precious from me and they gave me so much power. Every time they murder someone they give another family that power.”

For Valerie, a Latinx woman with a Latinx son, the Black Lives Matter movement has embraced her, they say his name during libations and it means the world to her.

Eric loved to skateboard and he jumped on one before he was one. His parents built him a little ramp to play on before he was 10 and as a teenager he worked with his father fixing up homes. Those details are precious to Valerie and she shares them with strangers, but she also wants to share them with Chief Michel Moore and DA Jackie Lacey.

A common goal for all the family members and community activists is to remove Jackie Lacey from office. All the interviewed families for this story said they would vote her out of office this November.

“We’re very clear that she’s the worst DA we can imagine,” says Melina Abdullah, Black Lives Matter Los Angeles co-founder and California State University Los Angeles professor. “District attorneys are there to prosecute folks and disproportionately it’s Black, Indigenous, people of color who are prosecuted by these DAs and that’s a problem. It’s Black, Indigenous, people of color who are killed by police throughout the country and they’re not prosecuting police.”

(The DA’s office declined to comment on this story.)

The rallies outside the Hall of Justice in downtown have swelled in recent months, but for nearly three years it was only the families sharing their stories. And over time the group has grown because more people have been killed.

“Almost without exception, all the families have been moved into activism in one way or another,” says Melina. “I think every family is in their own category. These moms come and tell their stories. I’m a mom. A lot of us are mothers and it’s difficult to hear their stories. Many times these are mothers, Black mothers, who are expressing their pain and anguish.”

For Valerie, a Latinx woman with a Latinx son, the Black Lives Matter movement has embraced her, they say his name during libations and it means the world to her.

Valerie says, “These families are my number one priority and to be a shoulder to cry on for them. Just to be able to meet them, to hear their stories, to share my son’s story. I’m hoping that eventually, the work I’m doing will make my son’s name known around the world. Because ain’t nobody else going to be talking about what happened to my son but me.”