By Dan Ross

This article was produced by Capital & Main, which is an award-winning publication that reports from California on economic, political, and social issues. L.A. Taco is co-publishing this article.

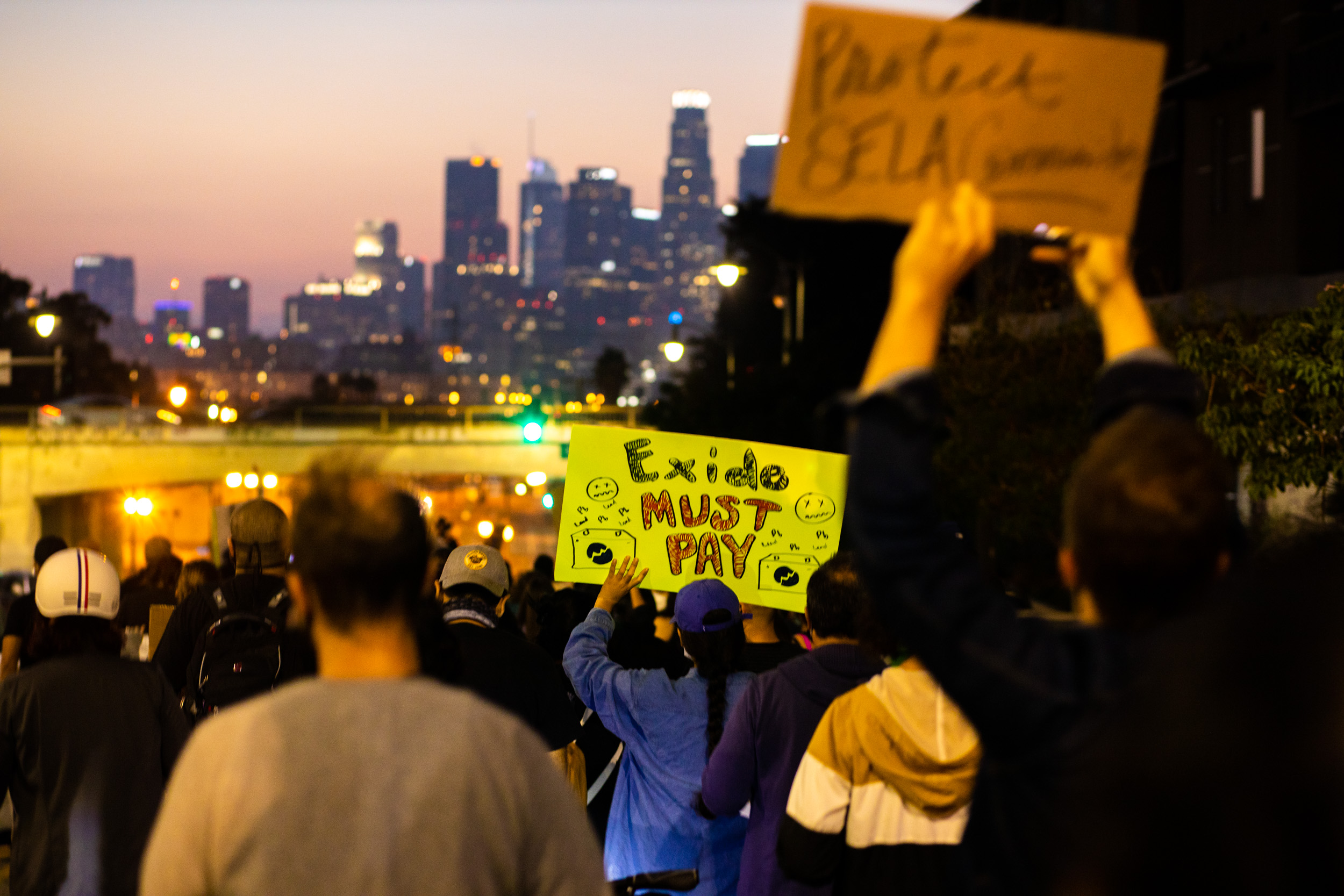

[dropcap size=big][/dropcap]The bankruptcy settlement reached between Exide Technologies and the Department of Justice (DOJ), recently inked in a Delaware bankruptcy court, was a bitter pill to swallow for many community members, environmentalists, and officials. It allowed, among other things, the company to essentially walk away from financial obligations to fully remediate its former lead-acid battery recycling plant located in Vernon, near downtown Los Angeles, along with the surrounding contaminated communities.

For those monitoring the state’s coffers, the agreement was especially galling as state officials had promised over many years that the more than $250 million the California taxpayer has put towards the residential cleanup would be reimbursed. The remaining work is expected to cost hundreds of millions more.

“They screwed the whole thing up by not securing the money when the money was there.”

In 2015 Barbara Lee, former director of the Department of Toxic Substances Control (DTSC), the state agency overseeing the cleanup, said, “We are looking to put a funding stream in place to get started. Then we will recover the cost and pay ourselves back as we go.” The agency also promised to “initiate cleanups and recover our costs later from all responsible parties, including Exide.”

The following year, Los Angeles City Councilman Jose Huizar called the $176.6 million of general funds then-Gov. Jerry Brown funneled towards the cleanup a down payment. The agency reiterated in 2018 how it was “holding Exide accountable” for the contamination, vowing at a subsequent L.A. City planning and land use management committee meeting to “pursue Exide to recover the costs of investigation and cleanup.”

Today these protestations seem moot, especially as the ruling’s profound long-term impacts are going to stretch far into the future. This leaves many who follow the project to demand answers to some tough questions: Could and should the state have done more to secure recovery costs from Exide? Are other responsible parties potentially liable? And how can the state prevent this from happening again?

* * *

Five years ago the U.S. Attorney’s Office entered into a nonprosecution agreement with Exide, essentially requiring the company to comply with the DTSC’s orders on the project in order to avoid prosecution. As news of the recent settlement agreement with the DOJ broke, various politicians and environmental groups saw it as an act of political betrayal by a Trump administration seeking to “punish” blue California.

But according to Jim Woolford, who led the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) Superfund remedial program from 2006 until earlier this year, the bankruptcy agreement was fairly standard. “There is nothing that struck me as out of the ordinary on this,” he said. And while it appeared that the DOJ tried to better meet the demands of other states than California, Woolford added, it doesn’t appear “on paper” as though the Trump administration cut a special deal with Exide.

Should California's attorney general have conducted a comprehensive investigation into the Exide caseafter its plant was shuttered?

Rather, Woolford explained how serious doubts surrounded the “ability of Exide to perform all the work” even before California took the lead on the project. Prior to that, there were discussions between the EPA and the state about putting the site on the National Priorities List—a ranking of highest priority environmental cleanups as part of the federal Superfund program—as a result of the sheer scale of the pollution at and surrounding the Exide plant, and the company’s ability to pay for the project. In other words, “Whether they would be viable and be able to carry things out,” said Woolford.

“I don’t know if their assessment of the corporate assets—[Exide's] ability to pay—I just don’t know how good that was,” Woolford added, speaking of the state. “That’s obviously an area in hindsight that wasn’t so good.”

Much of the controversy centers on how the state allowed Exide to operate for 33 years on a temporary permit and failed to ensure that it post adequate financial assurances as required by law.

The state’s ability to secure recovery costs from Exide, other experts claim, was hindered by a string of decades-long failures to hold Exide accountable.

According to Angelo Bellomo, former deputy director of the L.A. County Department of Public Health, “the real story” revolves around how the state allowed Exide to operate for 33 years on a temporary permit, how it failed to ensure that the company post adequate financial assurances as required by law, and how the federal government, rather than California, took the lead on finally shutting Exide down. Combined, these factors “compromised their ability to be tough on Exide,” Bellomo said.

“Had the state attorney general been the lead on this, with assistance from the feds on the criminal case, it probably would have ended up very differently,” Bellomo added. “They screwed the whole thing up by not securing the money when the money was there.”

Barry Groveman, former head of the Environmental Crimes/OSHA Division in the L.A. County District Attorney’s Office, said that after Exide was shuttered, the state attorney general’s office should have conducted a comprehensive investigation into the case—how it happened, who’s culpable, and who are other potential responsible parties—with a view to drafting a roadmap for avoiding a repeat at other contaminated sites in the state.

“There’s never been accountability for any of this, and nobody’s afraid of anything,” Groveman said.

“Exide is just an example—a superclear, very visible high interest example—of a more structural failure in how we deal with pollution.”

Capital & Main repeatedly sought comment from the attorney general’s office, which each time directed requests to the DTSC. “When we represent a client, we refer all inquiries to the client,” a spokesperson wrote in an email.

When asked what specific actions the DTSC took to ensure cost recovery from Exide, an agency spokesperson wrote that it secured $26.4 million in financial assurances from the company for the facility cleanup.

“DTSC also required Exide to pay costs DTSC incurred to oversee Exide’s closure work and corrective action work. DTSC invoiced Exide for oversight costs, and DTSC has filed Proofs of Claim in the bankruptcy seeking recovery of the outstanding balance,” the spokesperson wrote. “DTSC has appealed the Bankruptcy Court’s order confirming the bankruptcy plan and will continue to fight to hold Exide accountable.”

But is the DTSC looking at other ways to recover costs?

Sean Hecht, co-executive director of the University of California, Los Angeles’ Emmett Institute on Climate Change and the Environment, was formerly a deputy attorney general for the California Department of Justice, representing the state on environmental and public health matters. He said that under the law, any party that arranges for the disposal of hazardous substances at a hazardous waste site “potentially could be a responsible party.” But in a case like Exide, cost recovery is “much harder” as legal “recycling exemptions” can protect parties that arrange for certain types of waste, including waste lead-acid batteries, to be recycled.

Hecht warned that the state could waste “a lot of time and money” if it decided to go down this route.

Nevertheless, given the Exide plant's history of violations, the exemptions might not apply in this case, said Groveman. "Exemptions are privileges and they are not extended to those who are not diligent, let alone negligent in their duty of care," he said.

“It’s the ultimate in hypocrisy at the expense of the people of East Los Angeles.”

Other experts look to fundamental revisions to the legal apparatus available to officials to hold polluters like Exide accountable for their damage. According to Lynn LoPucki, distinguished professor at the UCLA School of Law and founder of the UCLA-LoPucki Bankruptcy Research Database, California needs an environmental “super priority lien statute,” as have other states including Illinois, Maine and Michigan. Such a statute would put the state, and the hazardous waste remediation it's overseeing, much higher up in the priority queue in the event the responsible party files for bankruptcy.

Angela Johnson Meszaros, the managing attorney for Earthjustice’s Community Partnerships Program, agrees that the bankruptcy system is “set up” to provide polluters legal avenues to escape accountability. By the time a case like Exide’s has made it to bankruptcy court, however, “It’s too late,” she said.

“Exide is just an example—a superclear, very visible high interest example—of a more structural failure in how we deal with pollution.” Assembly Bill 995, a DTSC reform measure that was sent to the governor’s desk at the end of the last legislative session, offered a potential fix by tightening things like the financial assurances that hazardous waste facilities post. Gov. Gavin Newsom vetoed the bill. “We have lost our way,” Johnson Meszaros said. “The polluters have pulled us off of our path.”

The bill is expected to be reintroduced at the start of the next legislative session. “I am 100% committed to continue working with stakeholders to fully reshape this entity into one that will prevent the next Exide and can oversee the management of hazardous waste in California in a transparent manner that fully protects all communities and public health,” wrote Assemblymember Cristina Garcia, a lead author on the bill, in a statement.

And what does the battery industry have to say about the case? Roger Miksad, executive vice president of the Battery Council International, wrote in an email how his organization is “disappointed with the level of funding provided through the bankruptcy process for the continued cleanup of the Vernon facility,” and that Exide’s membership in the association was suspended in July—two months, however, after the company’s latest bankruptcy filing.

Aside from political and regulatory miscalculations, the Exide case represents a failure by officials to protect the state’s most vulnerable, said Groveman, who singled out Attorney General Xavier Becerra—whose constituency, when he was a state assembly member, included neighborhoods that overlapped with those in the residential cleanup—for pointed criticism due to his very public environmental justice stance. “It’s the ultimate in hypocrisy at the expense of the people of East Los Angeles.”

Copyright 2020 Capital & Main