[dropcap size=big]T[/dropcap]here is an incredible moment of archival footage in the documentary Dolores, in which a television interviewer asks labor leader Dolores Huerta what she would do, thinking as an ‘average woman,’ if she had $5,000 to spend on ‘herself.’

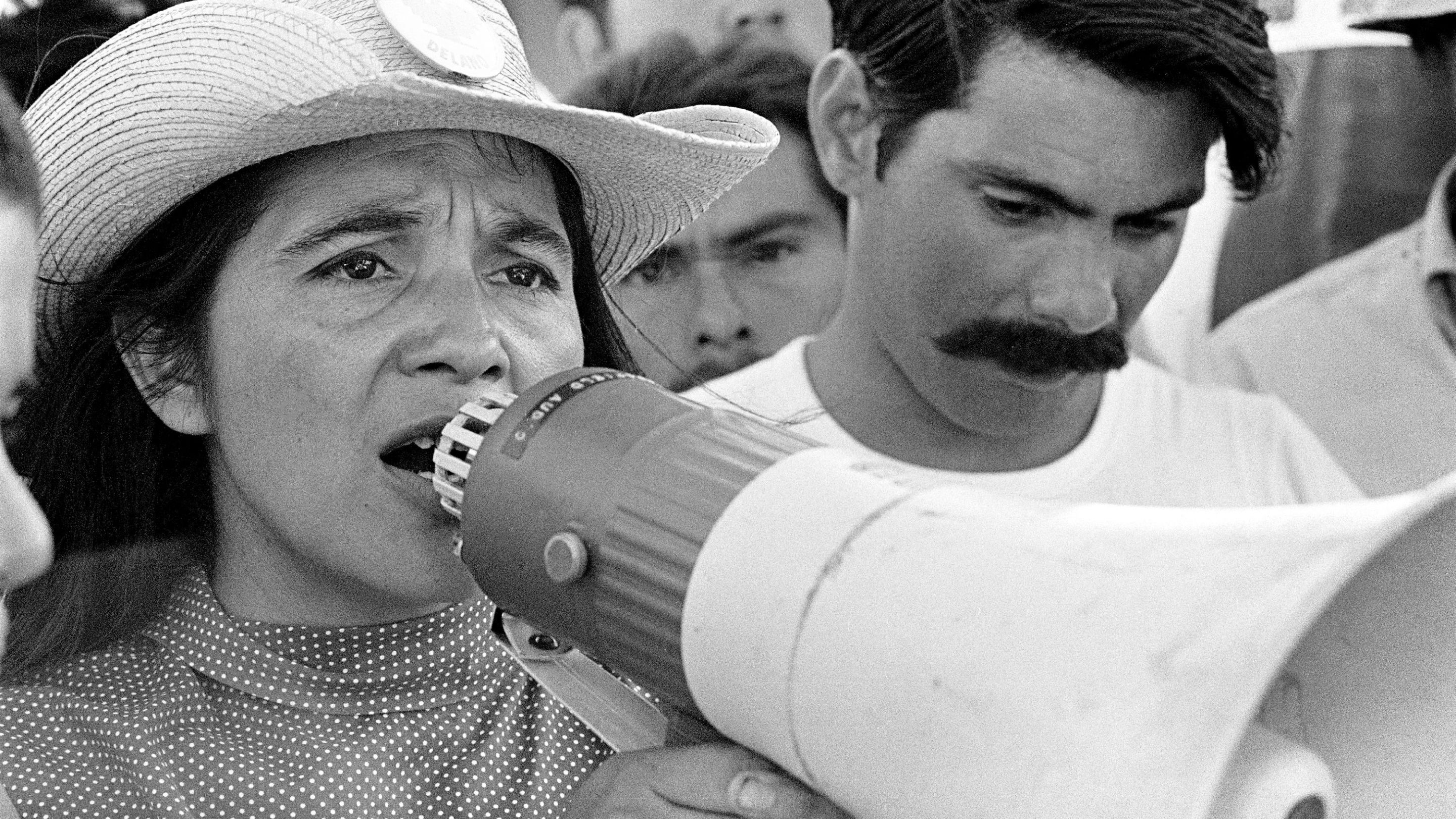

It is the second or third such patronizing question — from a woman interviewer, no less. Huerta fields them with an empty swallow and a smile that seems to be pleading for mercy at the idiocy of it all. Cesar Chavez, her cohort founder of the United Farm Workers, sits serene-faced right besides her, but silent.

At the time Huerta and Chavez were basically inventing modern grassroots organizing as we know it, while building the UFW in the breadbasket of the United States, California’s Central Valley. But you know, let’s talk about lady things.

“I’d donate it to the union,” Dolores answers after a laugh. But the interviewer is dissatisfied. “—That would be spending it on myself because to me ... this is my life’s work.”

The interviewer insists, begging Huerta to picture herself being pampered. Dolores can’t even anymore. “Well to me, having a hairdo and being in a spa would be a terrible waste of time,” she says.

Dolores, which got its terrestrial television premieres Tuesday night and as of Wednesday morning is streaming for free on PBS.com, shows how Huerta endured rabidly sexist moments like this throughout her life and career. Ever polite, ever smiling in that warm yet slightly terse way, and never wavering before stupidity — or hate.

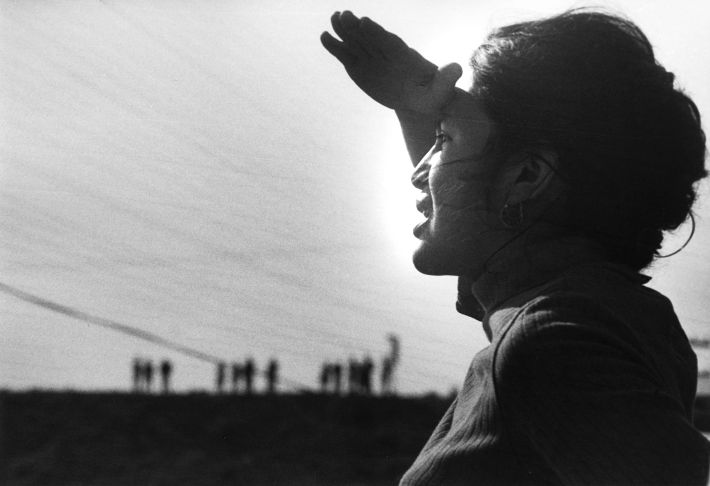

Dolores Huerta has spent decades both in the spotlight and in the wings. She was overshadowed by Cesar Chavez historically, but still found her way to the frontlines of every national social movement since the Civil Rights Era to today. Through her activism at California’s grape crops, she is credited with helping shape the very concept of environmental justice, where the people in the environment matter as much as the environment itself.

In the UFW, Huerta designed organizing strategies for workers and voters that revolutionized elections and laid the foundation for the Democratic supermajority we have in California politics today. In short, she is the embodiment of what can be achieved with tireless and unflappable grassroots activism.

Although Huerta and Chavez did everything side by side — and argued through every major decision, jointly — it was Chavez who for many years got most of the historical and public credit for forming the United Farm Workers. Wasn’t Dolores there from the beginning?

[dropcap size=big]W[/dropcap]ith this question in mind, Dolores, directed by Peter Bratt and co-executive produced by Carlos Santana, seeks to correct the record on Huerta’s legacy, firmly revising her historical role from sidekick to peer.

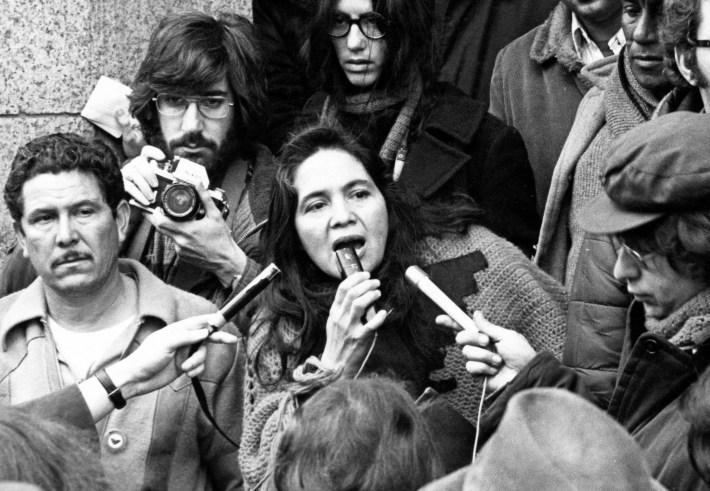

The film premiered at Sundance in 2017 and might have gotten overlooked in the political chaos of the start to the Trump presidency. By last year, Huerta for many of her generational supporters had become synonymous with status quo centrist electoral politics, an abuelita-like symbol of the Latino generational split in the 2016 Democratic primary.

With her role in the internal fight on the left between Hillary Clinton supporters and Bernie Sanders supporters, the 87-year-old leader solidified her reputation as something of a fearsome kingmaker in statewide politics. Clinton, whom Huerta steadfastly supported, beat Sanders among Latinos overall in California by 13 points.

But by then, more disruptive or dissident figures had been muscling into the media, a climate Bratt acknowledges. “We definitely had no way to foresee the election, through such a tumultuous time,” Bratt tells LA Taco in a recent interview. “When we started making the film, Barack Obama was president and supposedly America was post-racial.”

Dolores, however, is a reminder that Huerta was the original disruptor.

The film lays out in crisp detail how Huerta went from unorthodox Sacramento labor lobbyist with the Community Service Organization, to co-founder along with Chavez and several Filipino leaders of the National Farmworkers Association in 1962. The United Farm Workers followed in 1965.

The union expanded across California and later into the southwest. Its blazing red flag and geometric eagle insignia became synonymous with organizing, with the freedom to demonstrate, and with Mexican American and California identity. In clip after clip, Huerta is clear about her mission and her goals, and how they were directly connected to those of other groups.

“The reason for the existence of the union is to try to get power to the powerless,” she says in one. “The farmworkers do not have any power to solve their social and economic problems. They’re faced by not only economic discrimination, they suffer racial discrimination. This is true of the Mexican farmworker, it is of the black farmworker, the Arabian farmworker, and sometimes even the poor white farmworker.”

The film is far more traditional and polished than last week’s major Chicano film biography, The Rise and Fall of the Brown Buffalo, by Phillip Rodriguez. Yet it still avoids outright hagiography when examining the role of Huerta in her family.

The viewer is asked to view Dolores Huerta as a woman torn between being a 24-hour mother to a total of 11 children, or giving herself entirely to the cause.

She was late to embrace mainstream white feminism, because as a Catholic, she was against abortion.

She is seen as choosing the cause — and the children, more than half of whom are interviewed as adults, must grapple with that. I mean, How would you feel if Dolores Huerta was your mom?

The theme is especially painful to watch unfold as the viewer realizes that throughout the documentary, her children provide the most illuminating details about Huerta. One of her sons, Ricardo S. Sanchez, sums up his mom poignantly: “My mom, she grew up in the 40s, you know, the dances, the be-bop, the swing. She’s an American girl.”

Huerta dissented with certain movements. She was late to embrace mainstream white feminism, because as a Catholic, she was against abortion.

At one point in the film, while answering sexist critiques about the amount of children she had, Huerta makes an almost biblical yet hippie statement. “I believe a relationship should bear children,” she says joyfully.

Huerta was out in the fields, doing the work, taking the great grape boycott to New York and beyond. The children knew how important the work was; she was also raising them among the farm workers, to live as them. But Dolores exposes with remarkable candor how a mother’s absence left scars.

Bratt’s storytelling effectively pushes the emotional impact of key events — the assassination of Bobby Kennedy at the Ambassador Hotel in L.A. in 1968; Huerta had just been at his side; the 1988 San Francisco police riot outside a George H.W. Bush rally that left the senior Huerta with broken ribs and a ruptured spleen; the death of Cesar Chavez in 1993, and Huerta’s exile from the UFW.

There is no resolution in Dolores on why Huerta left the union. There is also no reckoning over why California farm workers still toil in miserable conditions, under threat, and live in poverty, despite more than 50 years of existence of the United Farm Workers.

Still, the power of Huerta’s legacy becomes palpable. Various contemporaries and admirers add to it, from Luis Valdez to Angela Davis. The voices emphasize that so many movements from that period — from the Black Panther Party to the Native American liberation movement — worked in concert, together. Huerta never stopped building connections.

“Today we talk about the intersectionality of struggle,” Davis says in the documentary. “But I think during that period, we actually lived it, we experienced it.”

It’s a relieving message to hear for a culture drowning in online echo-chambers of “calling out” and “but-what-about-this?” discourse. The film Dolores, through Huerta's example, asks viewers to just get up to do.

Making Dolores available for free streaming is an enormous boon to educators everywhere.

RELATED: The Rise and Fall of Oscar Zeta Acosta: What Happened to the ‘Brown Buffalo’