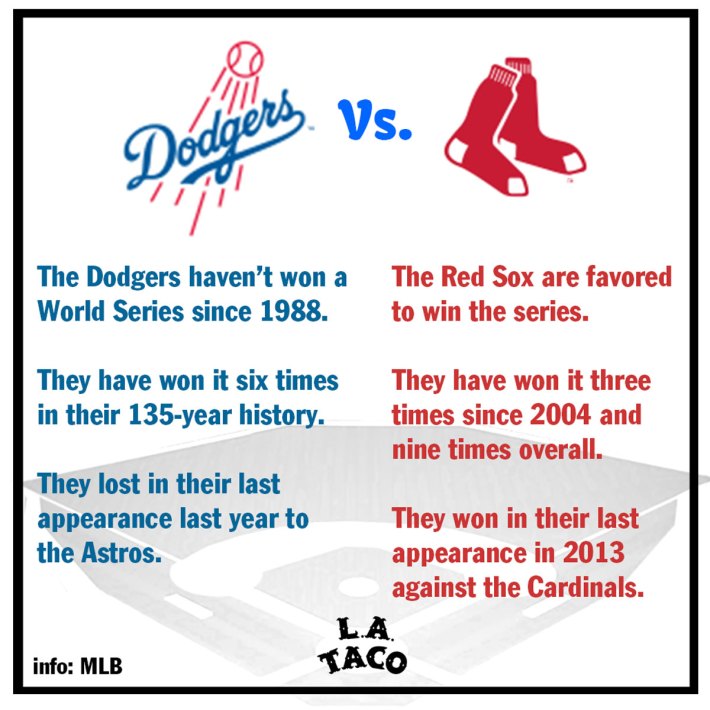

[dropcap size=big]I[/dropcap]t’s the World Series matchup the television executives were drooling over – the Los Angeles Dodgers against the Boston Red Sox – two of Major League Baseball’s most storied franchises, facing off in two of its most lucrative media markets.

Both of these teams possess histories that are deeply woven into the fabric of the sport. They are similar in a lot of ways, both rich with success and both teeming with influence on the historical arc of Major League Baseball. But there are also some stark differences between them, differences that spawn both shame and glory, and which been crucial in guiding the disparate paths these teams have taken to get this point.

Tonight, the Dodgers face the Red Sox in Game 1 of the 2018 World Series.

Curse of the Bambino

[dropcap size=big]T[/dropcap]o understand how important this matchup is, you have to go back to the last time these teams faced off in a World Series — in 1916. The Dodgers were based in Brooklyn then, and they weren’t even called the Dodgers, but the Robins, after their manager Wilbert Robinson.

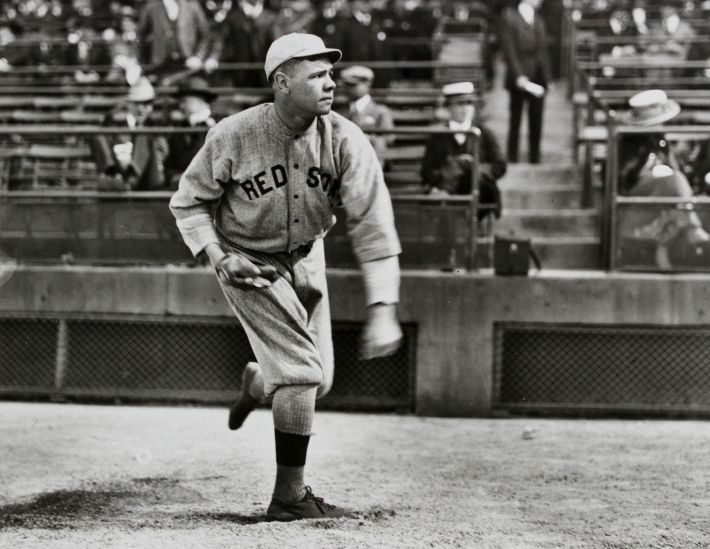

Boston had a player at the time named Babe Ruth, though he was known more for his pitching than his slugging at the time. He would play a crucial role in the World Series – pitching a 14-inning complete game in Game 2 – and Boston would defeat the Robins in five games.

Three years later Ruth held out for a better contract, and Boston owner Harry Frazee responded by selling him to the Yankees for $100,000. That move obviously had a huge impact on both the Yankees and Red Sox from a talent standpoint, and it also birthed what superstitious types call “The Curse of the Bambino,” a legendary and all-too-convenient excuse for the team’s 86-year championship drought that followed.

RELATED: Support Stories Like This & Become a Member of L.A. Taco Today!

Jackie

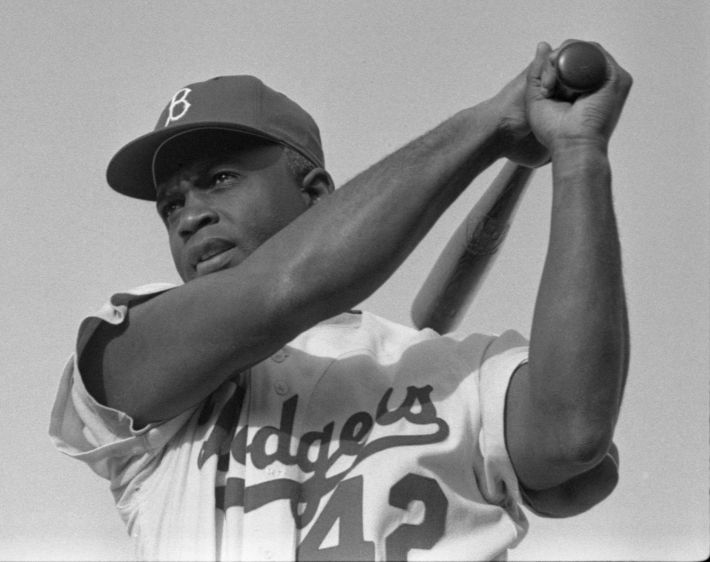

[dropcap size=big]T[/dropcap]he same year Ruth was traded, 1919, a sharecropping couple in Cairo, Ga. – Mallie and Jerry Robinson – welcomed their fifth child into the world. They named him Jack, though he would become famous later as Jackie.

And that’s really where the story of these two franchises diverge. Dodgers fans know the story well: In 1945, Dodgers executive Branch Rickey signed Robinson to a minor league contract, and Robinson would break Major League Baseball’s color barrier two years later. Rickey was innovative and an astute businessman, but there was also idealism in play, as Rickey was once quoted as saying “I may not be able to do something about racism in every field, but I can sure do something about it in baseball.”

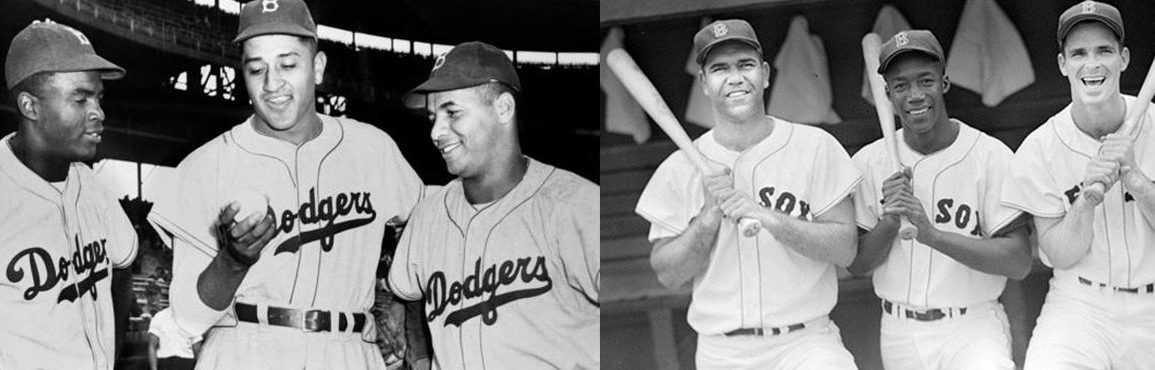

Rickey seemed true to his word and brought in other black players – the Dodgers’ championship team of 1955 had five African-Americans (Robinson, Roy Campanella, Jim Gilliam, Don Newcombe and Joe Black), and Afro-Cuban Sandy Amoros).

In the years since, the Dodgers have continued to innovate. They were the first team to invest heavily in Latin America when they opened the Campo Las Palmas baseball academy in the Dominican Republic in 1987. They were the first franchise to sign a player from Korea (Chan Ho Park, 1994), and the second to bring in one from Japan (Hideo Nomo, 1995).

Meanwhile, the Red Sox charted a very different course. Those with a more favorable viewpoint might call it a lack of innovation and resistance to change. But that seems more like a whitewashing of simple racism than anything else.

Regardless, the Red Sox were in fact the last team to integrate when they signed “Pumpsie” Green in 1959 – not just 14 years after Rickey signed Robinson, but three years after Robinson ended his Hall of Fame career.

RELATED: Two Male Dancers Make L.A. Rams Cheer Squad, Marking First in NFL History

Boston Common

[dropcap size=big]B[/dropcap]oston’s reputation – not just the franchise but the city itself – has unfortunately not improved much over the years. Celtics legend Bill Russell once referred to Boston as a “flea market of racism,” and baseball star Barry Bonds said he would never play for the Red Sox for that very reason.

As recently as May of 2017, Baltimore Orioles outfielder Adam Jones said he endured racist taunts, was called the N-word a handful of times and had a bag of peanuts thrown at him during a game in Boston. Red Sox ownership apologized immediately, but black players around the league nodded knowingly, and Yankees pitcher CC Sabathia said “There’s 62 of us. We all know. When you go to Boston, expect it.”

This is not to suggest all of Boston is racist, nor that current ownership enables such behavior. Nor is it to say the Dodgers are perfect — the removal of Mexican American landowners from Chavez Ravine to make way for Dodger Stadium is a particularly dark moment in this region’s sports history.

But it is troubling to consider how deep-seated such attitudes must be to still exist today. How can a fanbase widely worship three Dominican stars – David Ortiz, Manny Ramirez and Pedro Martinez – who did so much to break the “Curse of the Bambino” in 2004, while simultaneously worshipping a white player from that team – Curt Schilling – who went on Breitbart Radio and called Adam Jones a liar? It’s complicated and it’s baffling.

RELATED: Koreatown’s Favorite Sports Bars Where You Can See the Dodgers

The Steal

[dropcap size=big]B[/dropcap]ne more historical note of interest from 2004: When the Red Sox were in danger of being bounced from the ALCS by the Yankees, they turned to a multi-racial outfielder, the son of a black Marine and his Japanese wife. That man came on as a pinch-runner and stole a base, sparking a rally that would lead Red Sox back from the brink of defeat and all the way to the World Series.

It was called “The Steal,” and the man was Dave Roberts, the current manager of the Dodgers.

And as we sit down to watch Game 1 of the World Series on Tuesday night (5:09 p.m. PT, FOX), it is worthwhile to consider the different paths the franchises have taken to get here, 102 years after they last met. These franchises are linked in so many ways, and yet in so many ways, they couldn’t be more different.