[dropcap size=big]W[/dropcap]ho writes a 258-page book about cowboys in 2020? Walter Thompson-Hernández does.

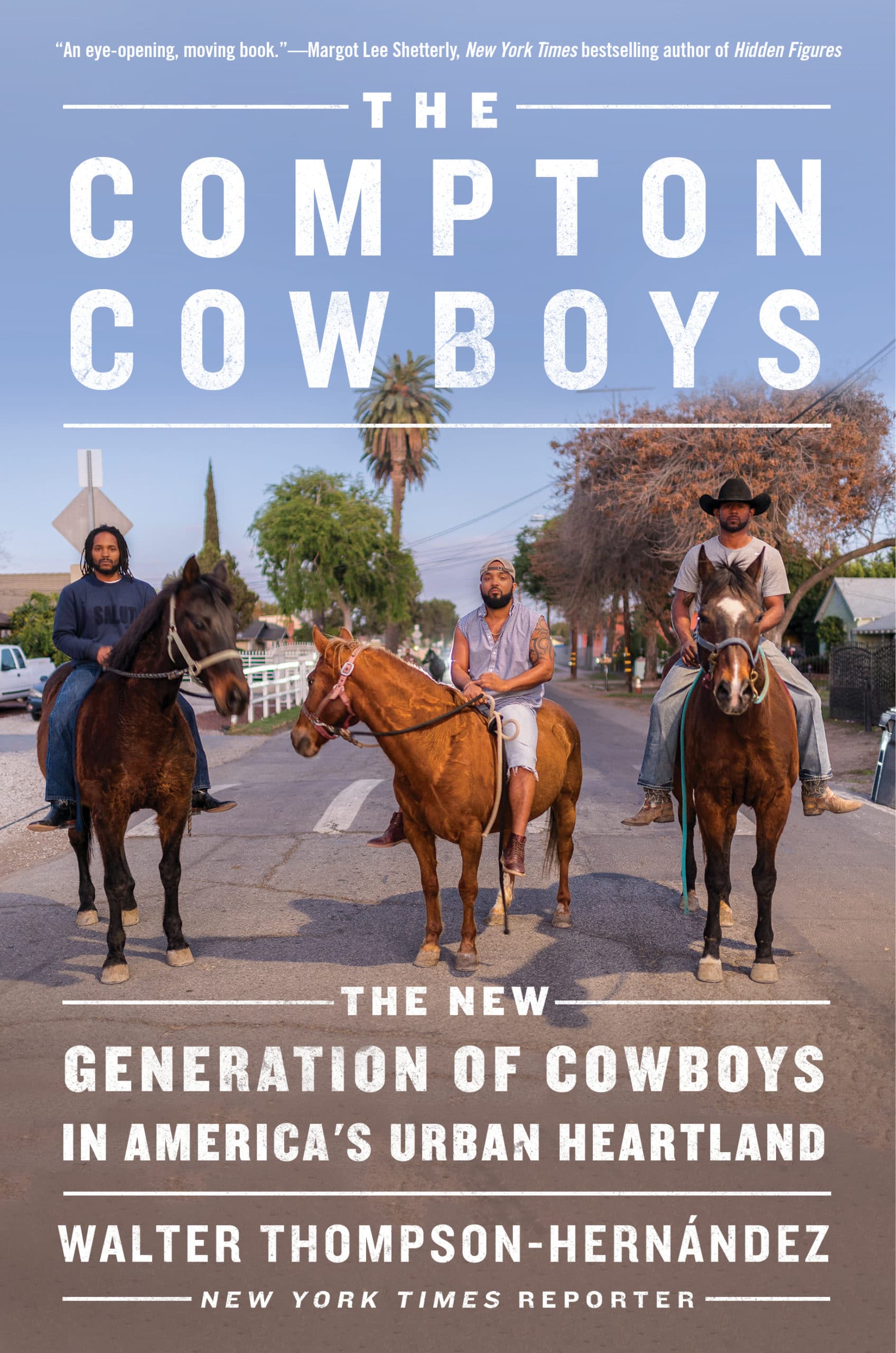

Born and raised in Huntington Park, the man has paid his journalistic dues. He’s covered everything from Chicano culture in Japan to the albino community in Ghana for The New York Times and currently is working on a podcast for KPCC. Somewhere between all of that productivity, he’s found the time to release his first book which is out today on a subject that is close to his street-hardened heart: The Compton Cowboys: The New Generation of Cowboys in America's Urban Heartland, published by William Morrow, an imprint of HarperCollins.

The book is the ultimate form of a story that Hernández wrote in 2018, where he broke down the complex lives of the last-standing Black cowboys in perhaps Southeast L.A.’s most notorious city, Compton. Through the use of vivid imagery and the cultural nuances that only a real L.A. foo who had both a Black and Mexican upbringing in Los Angeles would be able to execute, he lays out the deep-rooted issues that blight the urban warriors who make up the Comptown Cowboy group. Inner-city racism between Latinos and Blacks, gang violence, police brutality, poverty, love, identity, and family as experienced by them and written by Hernández is laid out in the book for all to see and hopefully feel.

It is set to go down as the next great American classic to have come out of Los Angeles, specifically following the lineage of ‘hood brilliance to have come out of Compton, California, so you can either support Hernández now or wait until his masterpiece is adapted for the screen later.

L.A. Taco caught up with Hernández on the big day before publishing his first book to talk about racism, access and trust as a journalist with the cowboys, and why this is an absolutely essential piece of literature if you consider yourself a prideful Angeleno.

L.A. Taco: So, what’s up? Why do people need to buy this book?

Walter Thompson-Hernández: Ah man! I think it’s a very important L.A. story. It’s a story about a community of friends who struggle to belong and are finding solace and a connection to horses. It’s an L.A. story we don’t generally tend to hear about and at the same time it is a very universal story. It’s a story about belonging, community, and a story about making spaces to heal. This space just happens to be a horse ranch in Compton.

How did you first find out about the Compton Cowboys?

My mom and I used to always shop at the Compton Swap Meet most weekends. I remember driving on Alameda Boulevard and I saw two Black men on horses, and it really fucked me up. At that point as a kid, I had never been taught that Black folks can be cowboys, right? I went back to school then to check and there was no recognition of Black cowboys. It was really confusing as a child.

Confusing because you had only associated cowboys with like Roy Rogers and paisas?

Absolutely. It was confusing because I'm half Mexican and I grew up going to Mexico every summer and winter break, so I knew Mexicans can be cowboys. I also knew about American cowboy culture in the West that was geared mostly toward white people. You know? Like John Wayne and the Marlboro cigarette guy. I was like, ‘oh shit! Black people can be cowboys too?’ It fucked me up in a great and confusing way.

In the book, you disclose that you’re proudly half Black and Mexican. You also immediately call out some deep-rooted racist stereotypes that aren’t the easiest to talk about. How did your bicultural upbringing affect the way you told this story?

That’s a great question. I spent almost a year and a half in the Richland Farms where the horse ranch is. What's really beautiful and incredible about this farm is that they're both Black cowboys and Latino cowboys there and what I noticed is that it’s their shared love for horses and animals that unites Black and Brown folks together in the farms. While that’s beautiful and really inspiring to see, what happens outside of the context of the farms and horses is different.

I think it'll be really hard for a white writer or a white journalist to have the same experience as I did because there are certain cultural and racial nuances that you can’t really learn in journalism school or in a grad school program. I think I was able to pick up on that nuances because of who I am personally.

Outside of these farms, Black and Brown folks are still dealing with racial violence towards each other. As someone who is Black and Brown, I understand the root of that tension. This is why it was really important, especially for me, to be honest about that stuff. As Brown folks, we grow up a lot of times harboring anti-black sentiments. As black folks, you know, we can also discriminate against Brown folks. For both, the root of this racism is often unfounded. It's founded on false stereotypes and cycles of violence usually on the media that aren’t rooted in complete honesty and truth. As a person who identifies as both, it is important for me to be honest about this.

Are there any similarities between Black and Latino cowboy culture?

For sure. I think there's there are so many similarities between the two. I think at the root of that relationship is an incredible amount of respect for horses and nature. That’s why I think this is such an L.A. experience. If you’re from Los Angeles and are from Mexican descent, you're probably a first or second-generation Chicano or Mexican Mexican, right? Well, if you are an African American, you probably have grandparents who came from the [American] south. If you look at it that way like we both come from rural experiences where horses were part of our upbringing. Black and Brown folks have this in common. Like this, I saw both Black and Brown cowboys riding their horses in constant, contradicting a lot of the stereotypes about each other as they rode. It was really beautiful to see.

How did you earn the trust of the Compton Cowboys to allow you to tell their story?

You know? I think it took some time. Because I am somebody who identifies as both black and brown and I’m also from the area helped. I don’t think people are dumb, especially if you grew up in the ‘hood. There, you grow up with a really strong sense of perception. My intention is ‘I'm here at all times and I'm just trying to tell a story in the most honest way. I'm not trying to exploit anybody.’

I think the way that erasure and history works are that most white folks have done a really great job of erasing the experiences of the people of color throughout time and throughout history.

The cowboys trusted me with their story because I was one of them essentially. We spoke the same language. We listened to the same music. We grew up with the same sort of experiences, and we both experienced similar trauma in our lives. I felt like I was accepted into the group in a way that was really special and unique. And yeah, I think like that my rapport was established really early on. I wasn't there in a voyeuristic way, but I was there in a way that really was trying to honor their story and I think they saw that.

Why do you think it took this long for Black cowboy culture to get some attention?

I think the way that erasure and history works are that most white folks have done a really great job of erasing the experiences of the people of color throughout time and throughout history. A lot of accomplishments done by people of color get whitewashed. I’m not the first person to document cowboy culture or to write about it but I am the first to document this group of cowboys in Compton. I think it was a really personal thing for me to do because I'm a part of this community. I think it'll be really hard for a white writer or a white journalist to have the same experience as I did because there are certain cultural and racial nuances that you can’t really learn in journalism school or in a grad school program. I think I was able to pick up on that nuances because of who I am personally. I'm really grateful to be a part of the cowboy cannon now.

Has the city of Compton embraced its cowboy roots or done anything to keep this tradition alive?

There's a lot more energy these days. I know, Randy, who's a manager and a member of the Cowboys, has been really advocating for more horse trails in Compton and some more awareness of its equestrian culture. I see it growing. I see the ranch working with the city and working with local schools because it’s a sanctuary. I see that hopefully prospering and growing moving forward.

How are the Compton Cowboys doing right now in the age of COVID-19?

They're not doing so well. They've had to suspend the youth program, which is where some of our funding comes from. They’ve had to sell some horses. A lot of the cowboys are now volunteering instead of getting paid. Donations are pouring in, but it's barely keeping them afloat and the ranch ultimately is still on the verge of closing down. This group of cowboys are so resilient and know how to persevere. They know how to make the best out of any situation. I know they’re going to make it.

Thanks for speaking with us.

The Compton Cowboys: The New Generation of Cowboys in America's Urban Heartland is available everywhere books are sold now. If you would like to make a direct donation to the Compton Cowboys to help them stay afloat during the pandemic, the link (vetted by Hernández) can be found here.