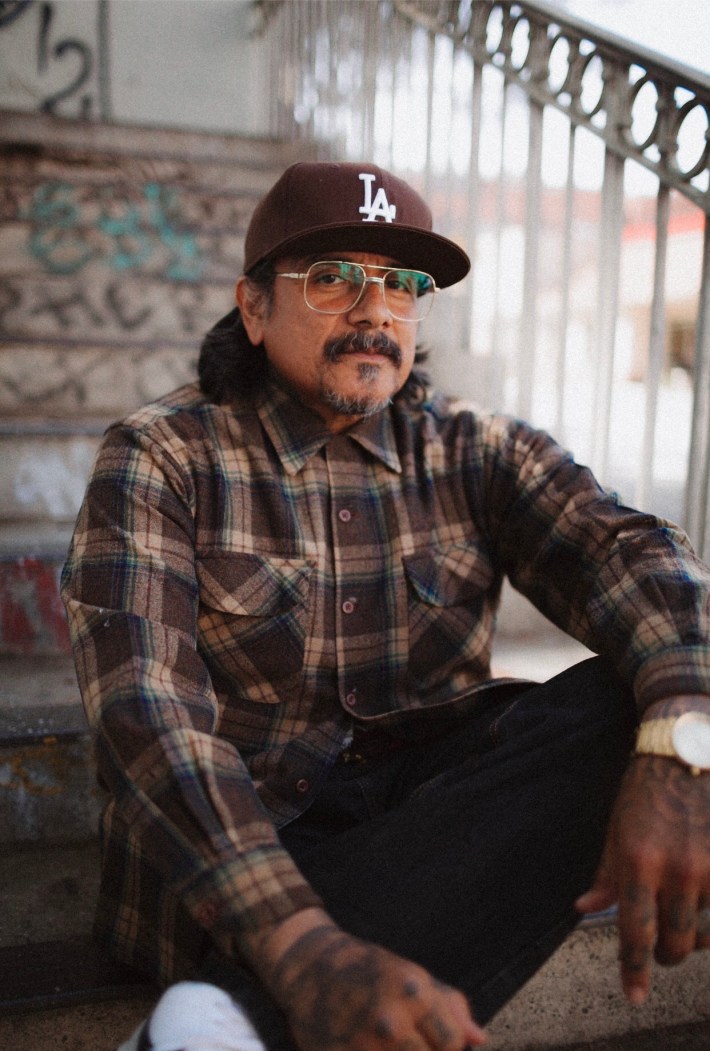

When I meet Jesse Jaramillo in Echo Park on a sunny September morning, he’s wearing a worn gray t-shirt tucked into rust-colored slacks. His sleeves are neatly cuffed, folded with such care my quickly curated outfit—Dickies overalls and a pair of dirty Chucks—starts to feel sloppy. His thrifted Playboy belt-buckle barely shines, but I notice it immediately. It punctuates his flamboyance like the period following a smooth, simple sentence.

His hair—a jet-black mound of curls—seems innocent, almost childlike, but his brown skin is strong, the latest shade in a long lineage. He has a gentle, soft-spoken confidence, the way people do when they really know who they are. He’s agreed to talk with me just before he goes into his job at Sal Preciado’s El Clásico Tattoo, one of the relatively OG businesses still standing on the heavily gentrified Sunset Boulevard in Echo Park.

“That shop has always been on my radar,” Jesse explains. “I could have easily gotten a job at any of these hipster shops that have popped up recently, but there’s nothing like El Clásico. The shit Sal had to go through to open a shop in Echo Park back in the day when no one wanted to be here is crazy. I like being a part of that history.”

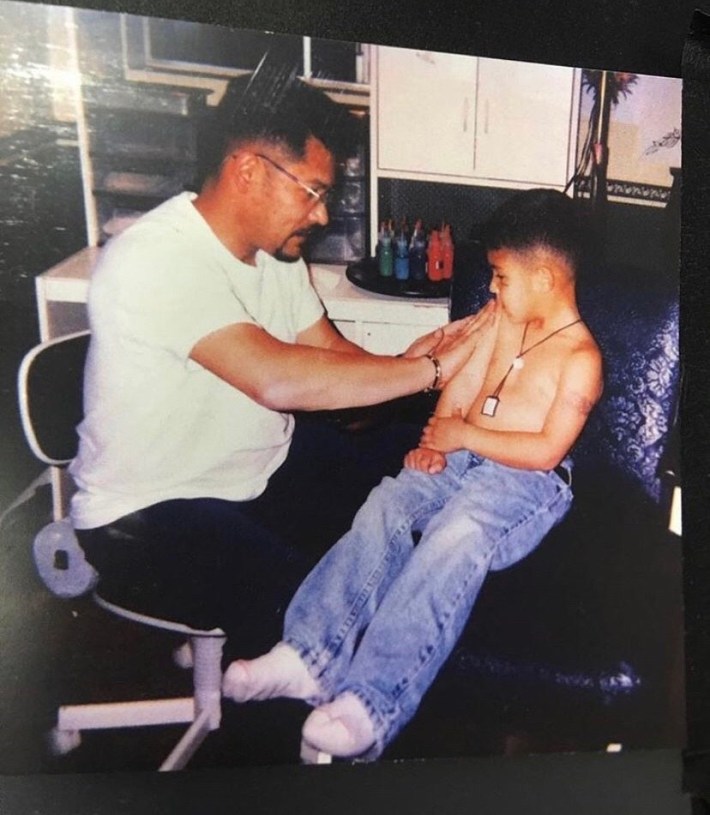

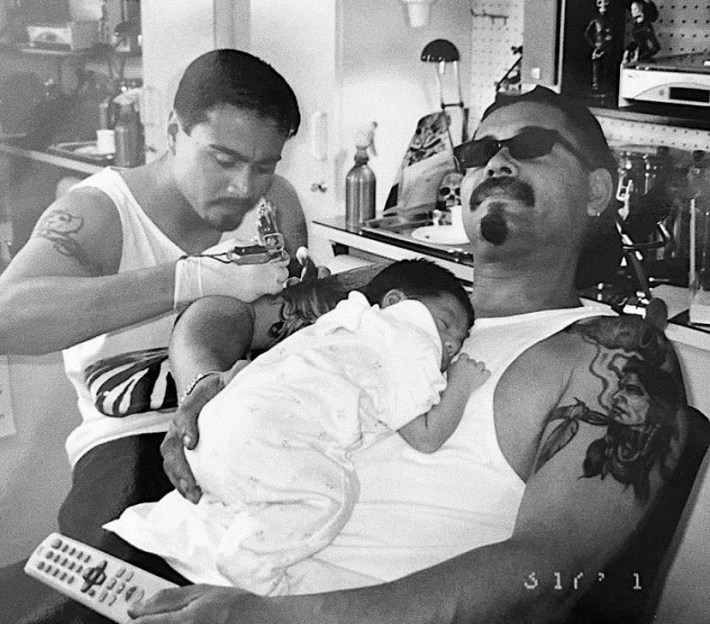

Though Jesse has been tattooing since he was 18 years old (he’s now 28), his apprenticeship under his father, Jesse Sr., began five years earlier when he was just 13. His dad, a former Edison electric employee and a self-taught artist has one of Jesse’s earliest drawings tattooed on his inner arm. The artist? Jesse himself. Years later, Jesse’s tattooing style is unmistakable, like his fashion sense. Salvador Dali meets Duke of Earl; liquified lowriders and crying cacti. A friend of Jesse’s once called it “trippy Chicano.”

“I’ve been drawing my whole life, but there’s one story that really marks the beginning: We were living in Lancaster at the time, and my dad was working at Edison. He’d just been laid off, and we couldn’t afford a babysitter, so he would bring me with him to the heart of L.A. to slang produce to the grocery stores. I always needed something to do to keep me occupied, so one day he gave me this receipt and a pen, and I ended up drawing this little turtle. He saved it in his wallet and still has it to this day. It was the first tattoo I ever did.”

Jesse’s partner, Xóchitl (they/them), is a student at Harvard University and a VJ for the school’s jazz station. The pair are newly in love in an old-school way—I can tell by the gold necklace around Jesse’s neck that reads “Xochitl” between tiny links and the way his velvety voice goes giddy when he explains how smart they are. His tempo subtly accelerates as he tells me Xochitl comes from a “dope mariachi family” and that the two have bonded while learning to accept their respective birthrights.

“It's interesting because we have this talk about growing up, Xóchitl and I. There was this point where I was almost embarrassed about doing Chicano work. No one was really doing that style of tattooing mainstream because it was still seen as ghetto,” Jesse explains. “And Xóchitl, at a certain point in their life, was embarrassed about wearing the traditional mariachi giddup, going out in public like that, and just being a mariachi in general. It’s so cool now, though, to be able to connect culturally.”

A month before our interview, Jesse drew up a dreamy event flier that looked like prison handkerchief art with pencil and paper. In warped and faded font, the flier read, “A Very Pinche Tattoo Party” (the “pinche” part was pulled directly from Jesse’s moniker, Pinche Kid, a nickname gifted to him after being the only kid at a handful of tattoo conventions.)

The location: Harvard University.

According to Jesse, tattoo parties are kickback-style gatherings where tattooing is done outside the industry’s control, amongst friends, family, food, and music. They’re a longstanding tradition in Jesse’s family, one he’s recently reimagined to subvert racism. Hours after landing in Boston, Jesse was hanging in the punk archive of Harvard’s radio station—WHRB 95.3FM—secretly tattooing Black and Brown students, including Xóchitl, who helped sneak Jesse and his supplies into the campus’ broadcasting quarters.

“This tattoo party was to perform a family tradition, but it was also to put a style that was considered ‘ghetto’ most of my life inside an institution with a racist past. It’s a tradition of social tattooing outside of the industry’s or the institution’s control. Traditions like these are part of a larger history constantly targeted and erased by white supremacy at schools like Harvard. One of the ways to combat this is to teach these histories ourselves. We have to teach ourselves ethnic studies—ethnic studies for us by us – which is what this tattoo party was: a celebration of our culture on our terms, without the institution’s permission.”

Deep within the oldest collegiate institution in America exists a small, stone plaque with four names engraved in it: Titus, Venus, Juba, and Bilhah. They are the names of the Black individuals enslaved by two different presidents of Harvard University throughout the 1700s. Elsewhere, another tiny plaque, no bigger than a piece of printer paper, reads, “In honor of the enslaved whose labor created wealth that made possible the founding of Harvard Law School. May we pursue the highest ideals of law and justice in their memories.”

“I’d be open to an invitation to tattoo at any of these universities, but I’d rather do it renegade style.”

This plaque is about the 27 enslaved men and women the university “inherited” when Isaac Royall Jr.—son of a “prominent” plantation owner and slave trader—died in 1781. Though these plaques (see: minute efforts) are meant to acknowledge and potentially eradicate the university’s heinous history, Harvard’s 2019-2020 diversity statistics suggest some heavy racist holdovers that feel inextricable from its past: 59 percent of Harvard’s faculty are white males, 21 percent are white females, and only about 28 percent of the ~23,000 students are Black and Brown.

What’s more, in early 2020, Dr. García Peña—a student-lauded Harvard professor who specialized in Latino and Caribbean studies—was denied tenure without explanation. This came shortly after Harvard’s Affirmative Action lawsuit wherein the university argued that race-based admission to the college was necessary to “create the diverse communities essential to their educational missions and the success of their students.”

Many students questioned Harvard’s motives, protesting at the admissions office with signs reading, “After you admit us, don’t forget us,” a statement undoubtedly derived from the school’s flimsy ethnic studies programs and resources. The institution initially built on the slashed backs of slaves now thrives on its ability to hush and hide minorities, all the while using their colored faces to promote the image of diversity.

“That was the thing about doing it at Harvard, there’s this big talk about ethnic studies, especially there,” Jesse explains, “And there’s this kind of responsibility on our part to push for ethnic studies at these institutions. This was a “fuck you” to institutions that try to use us solely for their benefit.”

The university had no idea Jesse was in their basement applying tattoo stencils with Speed Stick deodorant or that his supplies were all neatly spread out across a small wooden table in front of a Sharpie’d shelf that read “United Snakes of America.” They had no idea that Chicano culture was filling the small, seemingly dilapidated radio headquarters, swirling like smoke, or that true and beautiful cultural practices were unfolding and seeping under the doors of their mostly monochromatic institution. It wasn’t so much a rebellion or insurrection as it was reclaiming a right. Culture cannot and should not be controlled or regulated. Jesse Jaramillo’s newfangled tattoo parties are seeking to ensure that Chicano art and its deep, dark history are recognized in the light.

Months ago, before I had even thought to sit down with Jesse Jaramillo to talk about life, art, and Harvard, I’d seen a comment on an Instagram photo of him that said, “Your hair isn’t even curly.” Jesse responded confusedly, “It’s on my head.”

Sitting across from him at the bookstore that day, watching the L.A. sun beaming hard on his hundreds of bouncing, black ringlets, I understood what he’d meant. Even though it was just hair, it was his to define. The commenter was trying to control Jesse’s perception. He didn’t let it happen, but it stuck with me, nonetheless. The heat that day caused us both to sweat slightly, and one wet ringlet started to unravel down the middle of Jesse’s forehead. It went completely straight and sat there for most of our interview, subtly rebelling against the rest of his hair. Jesse didn’t seem to know or mind, and it didn’t change a thing.

But when we’d finally finished the last of our beers and went our separate ways, I still wondered why people want so badly to control each other, why they feel it’s their responsibility to stifle the reality of others. The thought wholly pissed me off until I remembered something Jesse had mentioned:

“I’d be open to an invitation to tattoo at any of these universities, but I’d rather do it renegade style. Xóchitl and I were talking about doing it all over again at Harvard, only this time we’d be out in the open where more people could see us.”