[dropcap size=big]S[/dropcap]omewhere off Las Tunas Drive in the city of San Gabriel, on a patch of rich soil where flowers bloom under the jardinero’s careful eye and guiding hands, lives the spirit of Elvira Moraga. The Tijuana-born Mexicana would marry an Anglo man with roots in Huntington Beach, raise three children, and live what her youngest daughter would later describe as an "unrequited life" in San Gabriel near the mission until her death from Alzheimer’s disease in 2005.

The daughter, Cherríe Moraga, would become an internationally celebrated essayist, poet, playwright, and profesora at Stanford University for more than twenty years. She would go on to write a prolific body of work that includes the groundbreaking collection of writing by women of color, This Bridge Called My Back (co-edited with Gloria Anzaldúa), a memoir of queer motherhood, numerous lectures and essays, and several plays that have been produced to wide acclaim. The publication of Loving in the War Years, her debut collection of essays and poems — many of them about the love of her mother — would put Elvira’s youngest daughter on the path to becoming a bonafide queer Chicana feminist literary icon.

Thirty-five years after Loving, Moraga finds herself back home, sort of, in Southern California. The Oakland-based, San Gabriel Valley native now teaches at UC Santa Barbara, where Moraga and her artistic partner, Celia Herrera Rodriguez, established Las Maestras Center for Chicana and Indigenous Thought and Art Practice in 2017.

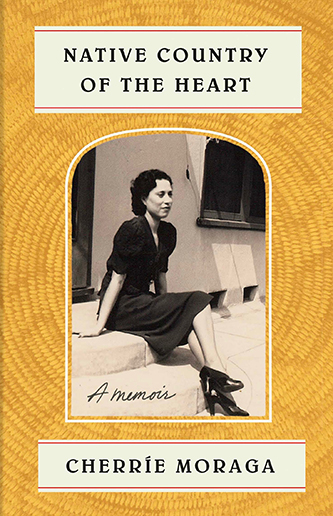

L.A. Taco caught up with the renowned writer on the eve of the publication of her latest work, Native Country of the Heart. A memoir about a Mexican mother, her Chicana lesbian daughter, and the loss of one’s memory, Moraga’s Native Country of the Heart maps a geography of cultural memory through shared stories of migrations, displacement, forgetting, remembering, and coming home again.

L.A. Taco: Let’s start with L.A. I was struck by your treatment of the greater Los Angeles area, as if the city at large is another character in the book. You take us around San Gabriel, Whittier, Montebello, South Pasadena, down to Yorba Linda and Huntington Beach. What do “L.A.,” Orange County, and place more generally mean in your memoir?

CM: I love that, place as a character. There was no telling this story without place. And it relates to memory. L.A. is all of it. Coming from Oakland and the Bay and Santa Barbara, "going to L.A." means going to San Gabriel and Yorba Linda, where my sister lives.

In writing the memoir, I had to really go home in a way that I never had done before, which meant I had to deal with San Gabriel, the mission, and L.A. I had to deal with all the lands, pulling up what I actually felt about the mission as a child. And to remember my "lesbian life" later in Silver Lake, Hollywood, West Hollywood because I had to get out of San Gabriel. I couldn’t be me as a queer Chicana.

The thing about Orange County to me—and having a memory of it as a kid going to visit my dad’s mom, my grandma Hallie, in Huntington Beach—is that it represents a period of great transition. The time was so little. We were free. It was a small town, but it also felt urban. It wasn’t touristy yet. Then years later, we did Digging Up the Dirt in SanTana, and suddenly it’s a Mexican Orange County. There was a Mexican cultura that wasn’t part of the Orange County I remembered as a kid growing up in the fifties.

The themes of memory and its connection to land feature strongly in all of your work, and this latest memoir is no exception. You call Native Country of the Heart “A MexicanAmerican Geography,” connecting your identity to lands, places, and histories. In our current moment of “Latinx” as term that would seem to replace “Latino/a” and “Chicano/a” to describe these US-based identities, could you explain your use of the term

"MexicanAmerican?"

I tried to be very specific about my use of terms. I use "MexicanAmerican," no space or hyphen, in writing about the culture of my family, the generations, and because it’s a true term. "Chicano" is a politicized word. It’s not true that my family would be called Chicanos. I describe myself growing up as "MexicanAmerican" because I had not yet come into my Chicana consciousness. Also, I couldn’t bring back the hyphen. We’re not hyphenated, we’re indigenous people. Get rid of the hyphen.

"Latinx" wouldn’t be true to the story, to the time period. I do use Latinx respectfully with young people. The word "queer" would arrive to me later, and I could look back at my queer self as a child. In Loving in the War Years, I didn’t have that language. I was a butch lesbian. That’s the truth of my queer body. And to say lesbian, that’s true. I’m a lesbian. It wasn’t even "gay." I said "I’m a homosexual" when I came out. But "lesbian" doesn’t suffice because so much of "queer" is about gender.

It’s a struggle for people to understand and be honest about vocabulary and vernacular. In intergenerational conversations, we have to be specific about our terms and be true to their meanings and histories. These terms reflect how we use language to mark these histories and our relationships to mestizaje, to indigenous identities through our lands, but also the contradictions of our identities. Some of these terms contain our histories of colonization. We’ve got to be able to look backwards to move forward, to understand that lineage. Fifty years is nothing. Let’s talk about the last five hundred years. We’re talking the decolonization of the mind.

RELATED: Fall in Love with Yesika Salgado: Silver Lake’s Fat, Fly, Salvadoran Poet

Speaking of the mind, you write about your Mexican mother’s story, from her migration to San Gabriel from Tijuana, her role as a worker, wife, mother, grandmother, and community pillar, to her gradual memory loss and death due to Alzheimer’s disease. How does your mother’s story connect to the broader myth of the “American Dream” and what you describe as “collective amnesia” in this country?

Indigenous cultures believe the land holds memory. In the dominant culture, that’s not valued, so we suffer from cultural amnesia as Mexicans in the United States. The American Dream means separation from ancestral, indigenous ways of knowing. Everything gets lost when it’s about tourism and malls and "making it" in this country. When there’s no land, there’s no native sensibility. We have to ask, what is our relationship to land? What is your memory? Because our histories of dislocation and mass migration mean we have to carry place with us through memory. We are as much of a place as we are of a people, therefore, every single place has a story.

I see dementia as really a gift of old age. When we see our elders losing their memory, there’s so much spirit. Dementia challenges us to ask, "who really is crazy here?"

My mother was in an elder care facility for dementia and Alzheimer’s patients in Orange County, the land of forgetfulness. Though she’s buried at Resurrection Cemetery, she planted herself on that patch of land at her beloved longtime home in San Gabriel. That’s her earthbound site of remembrance.

My mother’s private amnesia is a public phenomenon. This book is about trying to stop this mass amnesia project for Latinos in the U.S.

As a book about memory, the loss of it, and what it means to remember, did you always plan to write this story as a memoir?

I never know what genre something will be until I write. I wrote Waiting in the Wings about the birth of my son, and now this one about the death of my mother. The memoir form is a very particular, elongated conversation that connects to feminist "the personal is political" kind of writing.

Some of this story in Native Country also lives in Mathematics of Love, which we produced in August 2017. The “Peaches” character in the play has dementia. She is also the mother of Malinche who sold her daughter into patriarchy. I incorporated the Malinche character, which was written by Ricardo Bracho, to tell the story of betrayal between women by passing on our internalized patriarchy. So, the genres here, the memoir and play, are in conversation with each other.

I hope that what I portrayed is a passionate and compassionate look at how my mother did that. Malinche she was not. But she was the legacy.

RELATED: Hood Herbalism: Wellness as Resistance, Not as Trend