[dropcap size=big]C[/dropcap]overing these protests as a Black journalist has been conflicting.

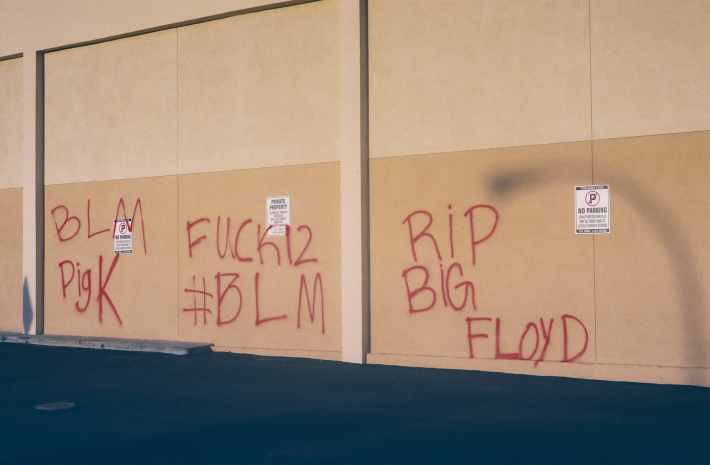

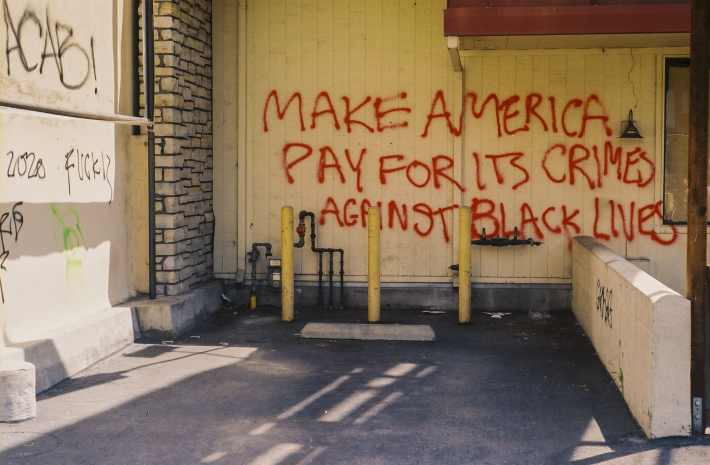

I’ve covered protests since I was an adult, including violent protests in New York City but I’ve never covered a protest like the one on Saturday, May 30th, 2020 near The Grove in Los Angeles.

That Saturday was one of the scariest and most tense days of my life. At times the Fairfax District felt like a one-sided war zone, a term I don’t use lightly.

What started off as a peaceful Black Lives Matter-led demonstration, abruptly escalated later that afternoon when the LAPD called a tactical alert and then later an unlawful assembly—tactics that the LAPD used to quickly redistribute officers to the area and round up protesters. Within hours of the initially peaceful demonstrations, anybody in the Fairfax area was subject to arrest, regardless if they were participating in protests or not.

LAPD just shot me and protestors gathered at Beverly & Fairfax with rubber bullets. I was holding my press badge above my head. pic.twitter.com/9YCXq3rUvc

— Cerise Castle (@cerisecastle) May 30, 2020

One thing I didn’t have to remind myself of that day was to always keep recording. After hours of crossing police lines and documenting the protests without any issues, an LAPD officer got physical with me after I turned my camera towards him and another police officer.

This sequence of photos represents less than 5 seconds of time and shows me getting jabbed in the stomach with a baton by an LAPD officer while reporting on Saturday. pic.twitter.com/a0nvRfxtRN

— Lexis-Olivier Ray (@ShotOn35mm) June 2, 2020

It took Officer Mia with the infamous LAPD Metro Division less than five seconds to turn to me, yell for me to “get back” before swiftly jabbing me in the stomach with the end of his baton. The blow sent my lanky frame flying back into a crowd of protesters who were kneeling down at the time and left my stomach sore for days.

I didn’t feel the pain for hours though. The adrenaline kept my mind off of it. The most difficult part of the interaction at the time wasn’t the pain, it was having to bite my tongue. Under different circumstances, I would have called the cop out. At that moment though, the cops were looking for a confrontation.

After getting knocked down and almost dropping my camera, I picked myself up, walked back up to the front line, and continued recording. A move that in retrospect, I think was more impactful than anything else I could have done at the time.

Here's a short clip of the @LAPDHQ officer jabbing me in the stomach with a baton, sending me flying back into a crowd of people. https://t.co/R3qUiBgZ5L pic.twitter.com/IIi9Yf9gOd

— Lexis-Olivier Ray (@ShotOn35mm) May 31, 2020

Capturing this moment on video and sharing it with the world on social media has led to interviews with some of the largest news outlets in the world, thousands of new followers, a surge in my film print orders and direct aid from readers and friends but it hasn’t necessarily led to a substantial amount of paid work (save for L.A. Taco, LAist, and KCRW), or done much to help me heal from the trauma of documenting the protests.

While I know the media world is struggling, I also know that White reporters are being sent to cover events that I have a deeper connection to and understanding of. It’s also difficult to accept the fact that I’m essentially putting my own neck on the line for pennies while other people get paid much more to report on it from home.

May 30 was just the beginning of a wild couple of weeks for me that included filing a lawsuit with the ACLU that challenged the constitutionality of the curfew orders, documenting dozens of arrests and protests, helping my fellow colleague and friend Samanta Helou-Hernandez get released from detainment, witnessing a Black Lives Matter weekly hall of justice rally swell to tens of thousands of people for the first time in two and half years, being mentioned in a Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors motion to protect journalists and much more.

I’m still reflecting on everything that has happened.

On one hand, I feel fortunate to be on the front lines of protests when so many staff writers and photojournalists are sitting on the sidelines but on the other hand, I sometimes feel guilty about the privilege that comes with being a journalist and conflicted over my interactions with law enforcement. One night when I was out covering protests, a protester said, “The media is just as bad as the cops,” before they were taken into custody. I wasn’t taken in, because I’m a journalist.

On one hand, I feel fortunate to be on the front lines of protests when so many staff writers and photojournalists are sitting on the sidelines but on the other hand, I sometimes feel guilty about the privilege that comes with being a journalist and conflicted over my interactions with law enforcement. One night when I was out covering protests, a protester said, “The media is just as bad as the cops,” before they were taken into custody. I wasn’t taken in, because I’m a journalist.

There have been many times in the last two weeks when I’ve wondered if it would be more impactful for me to put my camera down and join the protest. But then I remember what my place in the movement is. Before heading out to the protest on May 30, I debated shooting video. I had been covering the protests from the sidelines before and worried that my camera might get damaged. After all, it is one the main tools I use in my trade of journalism and how I earn my living.

The simple decision to bring my camera along for the ride is what ultimately led to all of this though. While my story is not unique—dozens of other journalists in Los Angeles and around the country experienced more serious acts of violence at the hands of the police. I was one of the only journalists to record their attacks on camera.

Since protests broke out in late May, I’ve spoken to a number of reporters about how we’ve potentially reached a turning point in journalism in a time that saw a pandemic delineate between “essential” and “non-essential” careers, journalists rose from the shambles to be the former. While it is a reporter's responsibility to be objective and fair, it’s also our job to expose the holes in our society. We can’t let objectivity harbor racism or violence.