Meta wiped ICE Sighting Chicagoland from Facebook last week. The group was used to warn users of ICE raids in the area and had nearly 80,000 members.

This comes just a week after Apple and Google removed all ICE-related apps, including ICEBlock, from their stores.

Both erasures followed public pressure from the Trump regime on Fox News and X, as well as venomous diatribes from extremist-influencer Laura Loomer. Although the tech companies claim it had nothing to do with the DOJ, pointing instead to terms of service violations, and denying they caved to any government coercion.

Whether they jumped or were pushed depends on who you ask. But one thing is certain: There was no court order or legal demand and the Constitution doesn’t require companies to erase lawful speech simply because officials want it gone.

“Apple, Google, and Meta were under no obligation to remove these apps,” says Alex Abdo, litigation director at Columbia Knight First Amendment Institute. “If they did it because the DOJ threatened them, even implicitly, that’s a First Amendment violation. The government shouldn’t be able to behave like a mob boss in going after protected speech.”

ICEBlock launched in April and by last summer was the third most downloaded free app. But as quickly as the app gained popularity, it drew fire from the Trump regime.

Kristi Noem denounced the app, warning, “If you obstruct law enforcement, we will hunt you down to the fullest extent of the law,” and attempted to prosecute CNN just for reporting on the app.

Loomer then doxed ICEBlock’s creator Joshua Aaron and his wife, who was fired from her government job the next day. The DOJ accused them (with no evidence) of “endangering ICE officers.”

A similar app, Red Dot, and its creator met the same fate after Loomer doxxed its creator, Nicholas Waytowich, a U.S. Army Scientist who was fired and is also now under federal investigation.

The First Amendment takes just 45 words to spell out, very clearly, that government cannot compel or suppress speech.

Private companies, however, can. But when the government pressures or coerces those companies to silence voices they can’t legally censor themselves, that’s called "jawboning;" and the courts have ruled for decades that jawboning is unconstitutional.

“It’s censorship,” Abdo says, raising the question of what good it does democracy when, as citizens, we have the right to scrutinize law enforcement, but it’s necessary to go through a private company’s technology to exercise these rights, giving them the power to decide what forms of protest you can take by what apps you can or cannot get at their stores.

"No one person or small group of people can effectively decide to shut down particular kinds of speech or dissent or discussion," Abdo says.

Abdo points out the hypocrisy, comparing ICEBlock’s removal to the continued existence of Waze, which still lets drivers flag police locations.

“The rules are suddenly different when it’s ICE?,” he says.

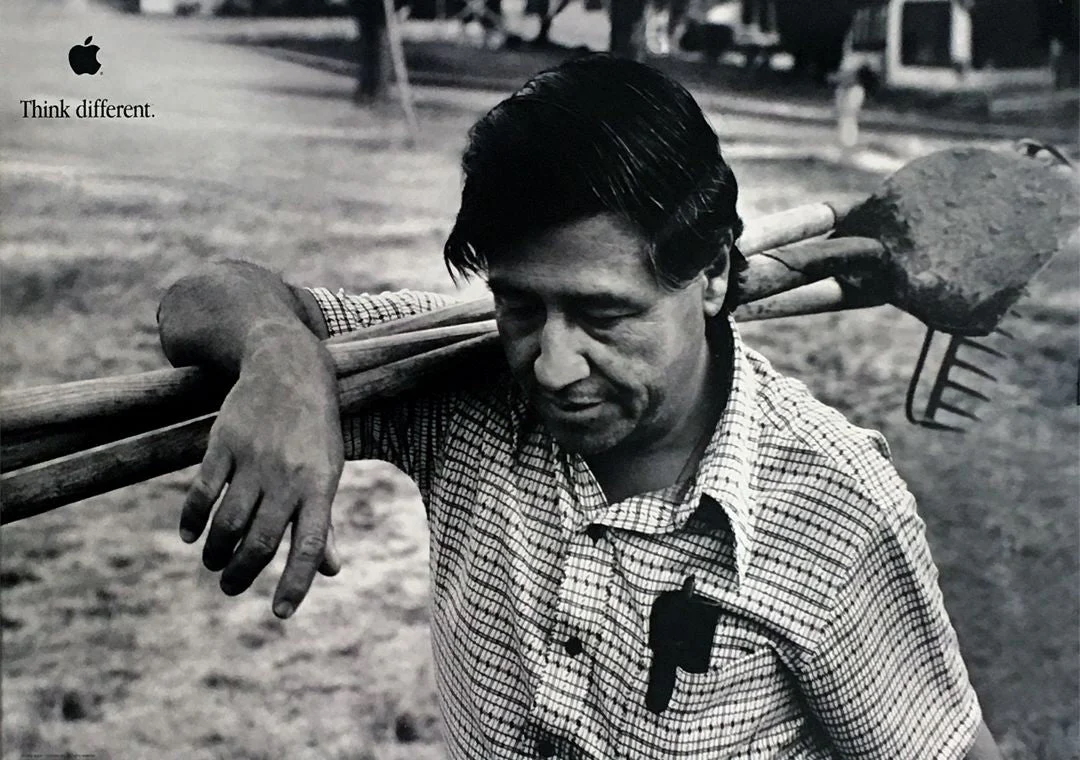

Apple once used Martin Luther King Jr. and César Chávez in its “Think Different” ads, deploying icons of resistance trivialized to sell gadgets. The irony isn’t lost on Abdo.

“They’ve thrown their users under the bus,” he says. “We shouldn’t be surprised. That’s what happens when companies grow so big and insulated they stop being accountable.”

Apple’s official statement about the take-down suggests there was a credible threat. Citing its broad “user safety” policy, the company states: “Based on information we’ve received from law enforcement about the safety risks associated with ICEBlock, we have removed it and similar apps from the App Store.”

But no evidence of those threats has been made public. Around the same time, Apple CEO Tim Cook was seen at the White House presenting Trump with a 24‑karat plaque after the president granted the company a tariff exemption on iPhones.

Google has denied that it faced government pressure, telling 404 Media that its app policies prohibit content promoting violence against groups based on “race or ethnic origin, religion, disability, age, nationality, veteran status, sexual orientation, gender, gender identity, caste, immigration status, or any other characteristic associated with systemic discrimination or marginalization,” but declined to elaborate further.

After a federal judge declined to break up Google’s search and ad businesses in a major antitrust case, Google CEO Sundar Pichai thanked President Trump, saying he appreciated that the administration had engaged in “constructive dialogue” and that he was “glad it’s over.” Google's parent company, Alphabet, added $230 billion to its market cap on the news of the ruling.

Meta also denied government involvement, saying the Chicago group ICE Sighting – Chicagoland “was removed for violating our policies against coordinated harm.”

In statements to The New York Times and ABC7, the company confirmed that the deletion took place shortly after the DOJ reached out, citing its rule against “outing” law enforcement.

Meta has been facing the most intense regulatory pressure of all three. An ongoing antitrust lawsuit threatens to force them to dump Instagram and WhatsApp.

At the White House's tech-bro dinner party in September, Zuckerberg sat right next to Trump, praising him for his leadership. The NYT reports that the breakup is now extremely unlikely.

We reached out to all three companies for the receipts, asking for documentation of those threats and whether we read correctly that they now count ICE officers as a protected group.

As of publication, they’ve left L.A. TACO on read.

Alex warns that government pressure, paired with corporate obedience, is a dangerous mix for our First Amendment right to hold law enforcement accountable.

“More people, more organizations need to have some backbone,” he told L.A. TACO. “We need individual acts of courage to show that dissent is possible. When you see a university or a law firm stand up to obviously unconstitutional efforts to silence political dissent, it’s contagious.”

His team recently convinced a federal judge to strike down Trump’s “ideological deportation” program that targeted foreign students and faculty for pro‑Palestinian advocacy. Over the past decade, Abdo’s lawsuits have pushed back on government overreach and defended free speech online.