Welcome back to L.A. Taco’s column, “Barrio Wisdom.” In this new series, we follow the streets-meet-academia wisdom of Dr. Álvaro Huerta, a professor at California State Polytechnic University, Pomona. In this installment, the third, we read a follow-up to the first and second essays on how growing up in the inner-city housing projects can teach you life lessons.

[dropcap size=big]W[/dropcap]hen I reflect and write about my experiences growing up in East Los Angeles’ notorious Ramona Gardens housing project (or Big Hazard projects), apart from my family, I always think about my childhood friends that I abandoned when I left to Upward Bound at Occidental College (during summers of high school) and UCLA (freshman math major): Javier, Teto, Ritchie, Buddy, Herbie, Ivy, Mayto, Tavo, Marty, Gino, Saul, and many more whose names escape me. (Actually, Teto also went to college.) There were girls, too, but we mostly self-segregated ourselves outdoors based on gender. (My sister Rosa hung out with her female friends, for example).

We all attended Murchison Street Elementary School and played street sports together in our urban village of bricks. Basketball, football (tackle and flag) and baseball. We rode our used bikes and skateboards. We played tag and Frisbee, occasionally breaking windows that the housing authority charged the residents to fix. No wonder we ran in all directions when one of us broke a window as if being chased by the cops! We didn’t need parental supervision or Spanish-speaking babysitters. There was no playing catch with dad. (It doesn’t help when many of my friends lacked a father in the household.) While we occasionally argued and fought, we mostly looked out for each other. We had each other’s back. Something that many outsiders aren’t familiar with.

Backing up your homies and learning the value of loyalty

In the projects, to have someone’s back is very important, especially when it comes to close friends (or homeboys). One day, Frank (pseudonym) asked me to have his back, as he challenged another kid from the projects near the abandoned warehouses. Let’s call the other kid Mario (pseudonym). While Frank was nine years old, Mario was 10. Like Mario, I was 10.

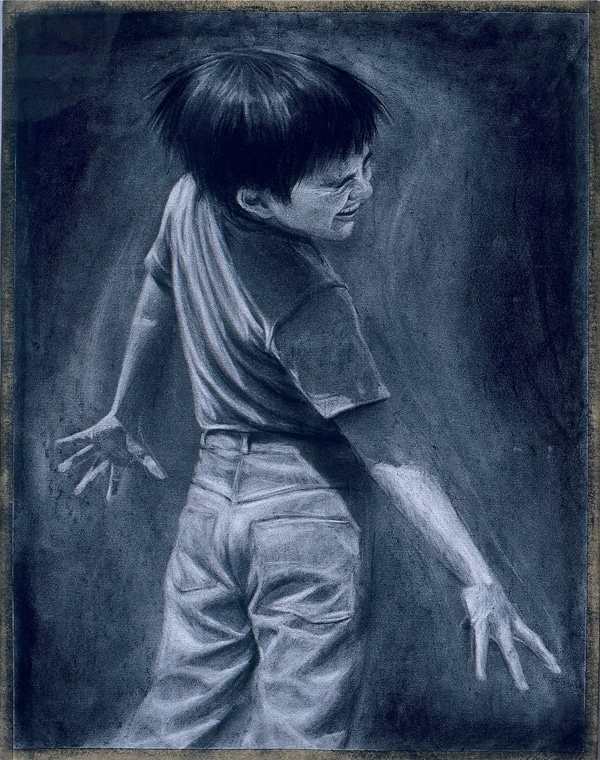

As a kid in a tough neighborhood, when you’re poor and live in a segregated, over-crowded neighborhood, all you have is respect.

Since both Frank and Mario had older brothers in the gang, they were fighting for respect and dominance amongst the kids in our section of the projects. As a kid in a tough neighborhood, when you’re poor and live in a segregated, over-crowded neighborhood, all you have is respect. Kids fight for respect all the time on America’s streets. While this might not make sense to outsiders, they must be reminded that American leaders have waged war for respect and dominance. This is the same, but street-level.

Going back to the showdown near the abandoned warehouses, while Mario arrived alone, Frank had me, along with another childhood friend, as back-up. As back-up, we’re only there to make sure it’s a clean and fair fight: mano-a-mano. Once we got near the abandoned warehouses, without saying a word, Frank and Mario started to throw blows (that means “fight” for the slang illiterate). While it started as an evenly matched fight, since Mario was bigger and stronger than Frank, he overpowered Frank, wrestling and pinning him down to the ground. Suddenly, Mario yelled and got in a fetal position. Frank quickly got up and said to us, “Okay, let’s go home.” I quickly realized that Frank had a screwdriver in his hand, as we left Mario agonizing on the pavement.

“You’re not dealing with a pushover.”

When I saw the next day Mario at school, he looked fine to me. Luckily for him, the screwdriver didn’t pierce through his skin too much. As expected, he didn’t complain or snitch.

As I reflect on this violent incident many moons later, where survival often depends on abiding by the rules and norms of the mean streets, I often think about the importance of loyalty and respect. This is not to imply that I condone violence. While I’m no fan of the military-industrial complex, I appreciate how the Marines’ motto of “leave no one left behind.” Throughout my life, whenever a so-called friend, an acquaintance, or classmate betrayed or disrespected me, I usually say, “It’s not your fault that you don’t know the value of loyalty and friendship since you didn’t grow-up in the projects!” I also nicely remind the offending individual to step back: “You’re not dealing with a pushover.” This also includes former and current bosses, professors, and colleagues.

The responsibility of paying it forward

Since elementary school, I always excelled in mathematics (or math). At Murchison Street Elementary School, while my classmates struggled with math, I thrived, as I visualized numbers, equations, and math problems, like pop-up books with three-dimensional pages. By the time I got to sixth grade, I received extra help from Ms. Rose. She taught me pre-algebra from a junior high school math book. With Ms. Rose’s help, I breezed through pre-algebra, as well. Throughout my many years as a student (K-12, university), Ms. Rose is my favorite teacher. While she believed that I could accomplish anything in the world, like my late mother Carmen, I still gave her a not-so-nice nickname: Mrs. Ronald McDonald.

I constantly remind them that they’re brilliant. I also remind them that they have the intellectual capacity to tackle any academic obstacle or problem in higher education.

Like Ronald McDonald, Ms. Rose was white with puffy red hair. Suddenly, all of the kids at school started calling her “Mrs. Ronald McDonald” behind her back. Part of me felt bad, but it’s not my fault she looked like Ronald McDonald! She was so cool that every year she took four boys and four girls (separately) to her cabin in Big Bear for a weekend trip. (This was the first time I ever went on a mini-vacation, especially since visiting my abuelitos in Tijuana doesn’t count. It’s not a vacation when the old black-and-white television, with the metal clothes hanger for an antenna, only gets one fuzzy channel.) While at Big Bear, Mrs. Ronald McDonald fed us spaghetti with ciabatta bread. After doing chores outside the house, we played tennis, like a bunch of rich, white kids from the suburbs. I still remember Javier using his tennis racket like a baseball bat, where, like Babe Ruth, he hit a few home runs over the fence! Those were the good old days when I bunch of Chicano kids played in a foreign land with no worries in the world.

Once I decided to become a professor, apart from the late UCLA Professor Leo Estrada, I said to myself, “When I become a professor, I want to be like Mrs. Ronald McDonald.” While I don’t own a cabin in Big Bear to take my top students to weekend trips, I treat them all with dignity and respect. While I also treat all students equally, in the particular case of first-generation students, immigrant students, students of color and students with disabilities, etc., I constantly remind them that they’re brilliant. I also remind them that they have the intellectual capacity to tackle any academic obstacle or problem in higher education.

In short, I inform marginalized youth (and others) that they belong in higher education and shouldn’t allow for anyone to make them feel otherwise. I do the same when I visit K-12 schools and other spaces in racialized and working-class communities. Moreover, I boldly challenge privileged outsiders when they hector to youth in America’s barrios and ghettos that “college is not for everyone.” Given my bleak background, where I overcame tremendous obstacles to secure three degrees from UCLA and UC Berkeley, I encourage brown and black youth to pursue higher education by promoting Dolores Huerta’s powerful message: ¡Si Se Puede!