Peter Arellano, a resident of Echo Park, is now able to sit outside on his porch with his father. He’s also able to wear Dodger Blue if he’d like to, or have an alcoholic beverage anywhere in public view.

These and other activities were potentially prohibited in Arellano’s day-to-day life and were temporarily lifted earlier this year by a federal judge as the city and advocates battle out in court over L.A.’s controversial gang injunctions.

Arellano was attached onto the Echo Park gang injunction in 2015 — without any charges or any hearing — because his father had been involved with a clique within an Echo Park gang. It turned his life into a state of “probation-like conditions,” as one ACLU attorney put it, despite Arellano’s claim that he is not a member of a gang.

So the ACLU and the Urban Peace Institute sued, on behalf of Arellano and another plaintiff.

On Sept. 7, a U.S. District Court judge granted the plaintiffs a preliminary injunction against their gang injunctions. For now, as the suit continues, they are free to be. And as a result of the case, officials at the LAPD and the city attorney’s office began auditing the rolls of its gang injunctions to see if other people might be on there unfairly.

This week the city attorney said it removed approximately 7,300 people from its list of 8,900 under injunctions, dramatically reducing the figure by 82 percent. That’s more or less an admission that the campaign to spread gang injunctions is ineffective, at least — if not unconstitutional, as its critics argue.

Additionally, the city decided in September to give people a chance to appeal their placement on a gang injunction within a 30-day period, and that any future injunctions will have a five-year expiration date unless new evidence surfaces to warrant an extension. Previously a gang injunction was forever.

GREAT NEWS! Our lawsuit in partnership with the @ACLU halts gang injunction use in #losangeles via @latimes #aclu #justice pic.twitter.com/YO3QSvzO81

— Urban Peace (@UrbanPeaceInst) September 8, 2017

Kafkaesque

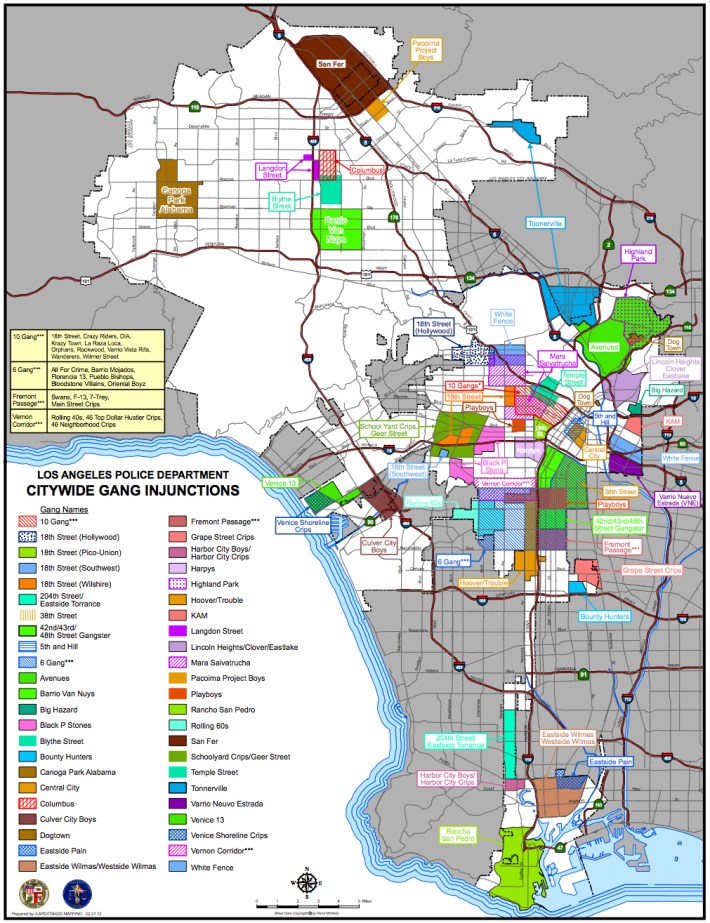

Gang injunctions create Kafkaesque scenarios, like people not being able to ride in cars together to places like school or church if they both appear on one. You cannot be seen “anywhere in public view, in a public space” with anyone else who appears on a gang injunction. According to the city, 46 injunctions are in place targeting gangs in L.A.

Melanie Ochoa, a staff attorney at the ACLU in L.A., said the city’s gang injunctions have proven themselves to have a “huge risk of error.” In an interview with L.A. TACO, Ochoa said worry is also growing that the injunctions are being used as tools in another process negatively affecting people’s lives: gentrification.

“That’s been a concern for a long time. In Echo Park, when this injunction came down in 2013, crime was at an all-time low in that neighborhood, and it was also gentrifying,” Ochoa said. The injunctions end up targeting and displacing “black and brown people,” she added.

Gang injunctions are a civil-criminal hybrid. An individual is placed on one because certain activities, dress, or behaviors are considered gang-related and therefore a “nuisance,” and are banned under a civil court order. Violating one is considered criminal contempt of a court order, and could lead to arrest — and jail time.

In 2015, journalist Sam Quinones told L.A. TACO that injunctions were only part of the reason that crime has dropped in Southern California since the gang warfare days of the 1990s.

“I believe gang injunctions have had a huge effect on gangs dispersing or moving indoors,” Quinones said at the time. “The Internet is keeping kids indoors. That’s another factor. There are many.”

Law enforcement leaders and advocacy groups argue the gang injunctions have helped reduce crime in Los Angeles and other cities, although researchers say that connection is tenuous and debatable. A spokesman for the city attorney’s office said letters were being sent out to the 7,300 people so far removed from L.A. gang injunctions in 2017.

“Many have steered away from gang life, having grown older and more responsible (‘aged out’) while others have left the neighborhood and no longer frequent the limited geographical area that the relevant injunction covers (‘safety zone’),” wrote Rob Wilcox, spokesman for the city attorney, in a statement. “Still others are in prison, while some have passed away.”

But that doesn’t mean that gang injunctions are over, or that the city no longer supports them.

“Based on the fact that they didn’t take everyone off these injunctions, to me, that lets us know the city of Los Angeles is not finished trying to enforce and use gang injunctions,” said Josh Green, staff attorney at Urban Peace Institute. “There is very limited evidence that gang injunctions serve any useful public safety end.”

Sean Garcia-Leys, another UPI attorney working on the case, also warned that the removal of these individuals from injunctions might not be reaching rank-and-file officers.

“We’ve already had a case of a person who received the [injunction removal] letter and was placed under arrest for an injunction violation,” Garcia-Leys told L.A. TACO.