On weekend nights in the late 1970s, Al Guerrero and his friends regularly drove around East L.A. looking for the clues that meant they were about to find a party.

They’d cruise up and down Whittier Boulevard, 3rd Street, or Beverly Boulevard, straining their necks to find lines of parked cars, dolled-up teenagers, or the thump thump thump of electronic bass synced to strobe lights.

Sometimes, Guerrero got help with a hotline; other times, flyers from record stores, schools, or friends told him where to search. And if Guerrero and his pals still couldn’t find the good times, there was always one last option: roll down the window of his blue 1977 Chevrolet Monte Carlo and yell at the car next to him, “Hey, do you guys know where there’s a party?”

Twenty minutes was all Guerrero needed to find a backyard disco oasis.

From Montebello to Monterey Park, to Boyle Heights, in steakhouses and Tiki bars, gyms, and parking lots, disco parties bloomed across the Eastside in the late 70s.

But talk to anyone that was a teenager in that era, and they’ll all agree that the best parties were in backyards.

That’s how Guerrero tells it, at least.

“[It was] almost like arriving at Emerald City or Disneyland,” the now-62-year-old recalls. “The streets would be jam-packed with hundreds of kids.”

Formerly humdrum personal outdoor spaces transformed into makeshift discotheques, complete with clandestine bars, a sea of colored lights, and teens who paid a nominal cover charge to get in, mesmerized into movement by the electro-disco sounds of European artists like Cerrone and Giorgio Moroder. For Guerrero, that feeling about being in someone’s yard where people are just genuinely having a good time, “You can’t duplicate it. It’s just very special. It was just such a sense of elation, a kind of celebration and joy of the music and the dancing.”

“Back in the day, we would party Friday, Saturday, and Sunday nights,” said James Rojas, who frequented and hosted backyard disco parties as a young gay Chicano in Boyle Heights and Alhambra in the late 70s. Rojas said he shopped at thrift stores for new outfits and practiced dance moves during the week in anticipation of weekend disco parties. “It was a 24/7 lifestyle.”

“People would dance for, like, four hours (straight),” said Ted Molina, a teenage DJ in those days who’s now considered a pioneer of the underground disco scene. “By the time you were finished dancing, any [drugs] that you did, you’d burn through.”

The backyard disco parties were “a merger of all different kinds of styles,” said Rojas. Today, he’s an urban planner and community activist known for his Latino Urbanism work, an approach that emphasizes the Latino experience in the urban design process. “Like unity between Black and Brown people everywhere, coming together with a utopian spirit.”

Disco music—marked by its elements of funk, soul, pop, and salsa—emerged in the mid-1970s in predominantly Black neighborhoods of New York and eventually made its way West. “In many ways, disco represented the ideal of integration as laid out by the civil rights legislation of the ‘60s,” wrote music critic Peter Shapiro in his 2005 book, “Turn the Beat Around.” Integration, gay rights, and women’s sexual reproductive rights all met on the dancefloor. “Despite the media’s focus on the elitism of Studio 54, it was and is populist music par excellence.”

This interpretation of a genre and scene long maligned by mainstream music critics manifested itself on the Eastside.

Former teenage DJ Mario “Vinde,” aka Vinde Champagne, remembered his East L.A. Chicano community looking for their own identity. “Before us was the Zoot Suiters and other things,” said Mario, who asked that his last name not be used in this story. “Rock n’ roll was cool, but the disco thing was what we hung onto and made it our own.”

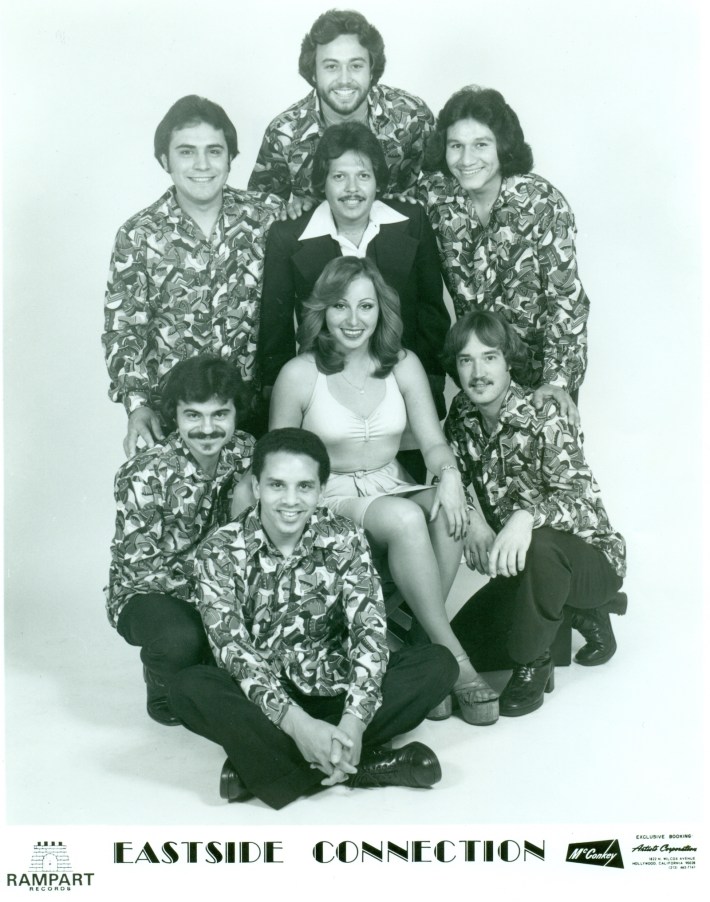

The genre didn’t stand out but rather fit in with other Latin dance music styles and tastes. Plus, said Hector Gonzalez, bassist, and bandleader of disco funk band, Eastside Connection. “la raza likes to dance.”

Do the Hustle

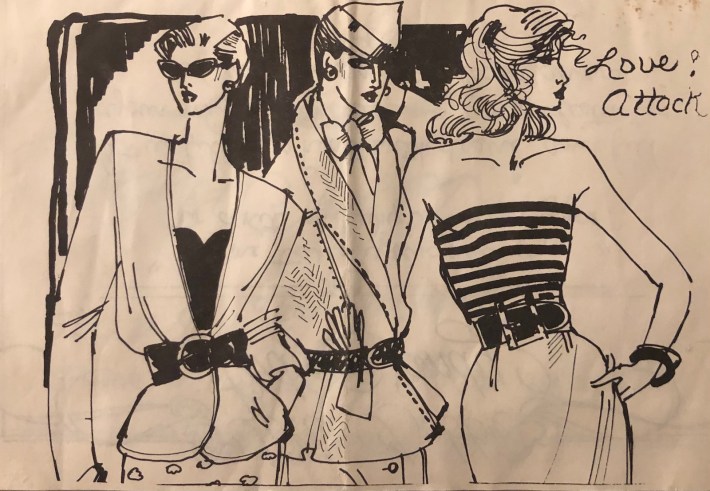

Talk to an Eastsider who was around in the late 1970s about disco today, and they’ll say there were three distinct scenes within the genre. The R&B and funk-forward disco lovers of the mid-1970s embraced artists like Earth, Wind, and Fire or KC and the Sunshine Band, complete with gravity-defying Afro perms and wigs. This look was popular at disco nightclubs, such as Hollywood’s Circus Disco and Westwood’s Dillon’s nightclub. (Young Chicanos donned Afros as an everyday look, “from senior pictures to prom,” said Rojas.) Mainstream disco, led by Donna Summer and the Bee Gees, dominated Eastside restaurants, bars, and clubs. The hip teens and music nerds seeking Italo-disco sounds from Europe dominated the backyard scenes.

They were all after the same thing: dancing, fashion, parties, and a chance to interact with the opposite sex or the same sex.

And everyone agrees: there was no Eastside disco scene at all until the 1977 release of “Saturday Night Fever.”

“Overnight, I got myself my Kiana’s shirt, platform shoes, puka shells, the whole bit,” recalled Molina, a former rocker that ditched his long hair and Led Zeppelin tees to become a disco DJ. “The way they make it seem in that movie is that’s a way you can meet girls if you dress cool.”

An L.A. Eastside blogger, who asked to be called Chimatli, said her husband was a former metalero who decided to cut his hair and wear bell bottoms after seeing the movie because “all the cute girls were into disco.”

Olivia Cadena Audoma of Montebello started listening to disco when she was a high schooler at Sacred Heart Catholic School in Lincoln Heights. “My brother and his friends used to come over, and I would teach them how to dance disco in the bedroom,” she laughed. She loved dressing up for nights on the dance floor. “The girls would wear the wraparound skirts so that when you spin, your dress would fly up in the air.”

Her older brother was part of a crew that threw parties wherever they could find a private backyard venue. “That's how people made money back in those days!” Cadena Audoma said.

Just as quickly as “Saturday Night Fever” became popular, there was a backlash. Younger people almost immediately derided its soundtrack and that of earlier groups—who had topped the charts not even two years ago—as “old disco” and began to foster their own scene.

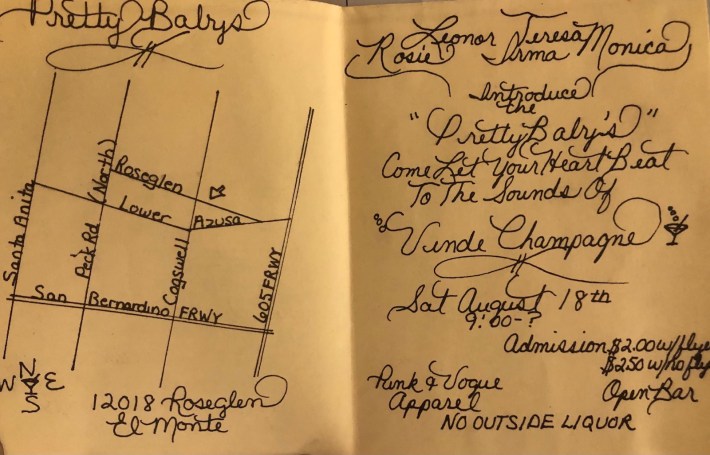

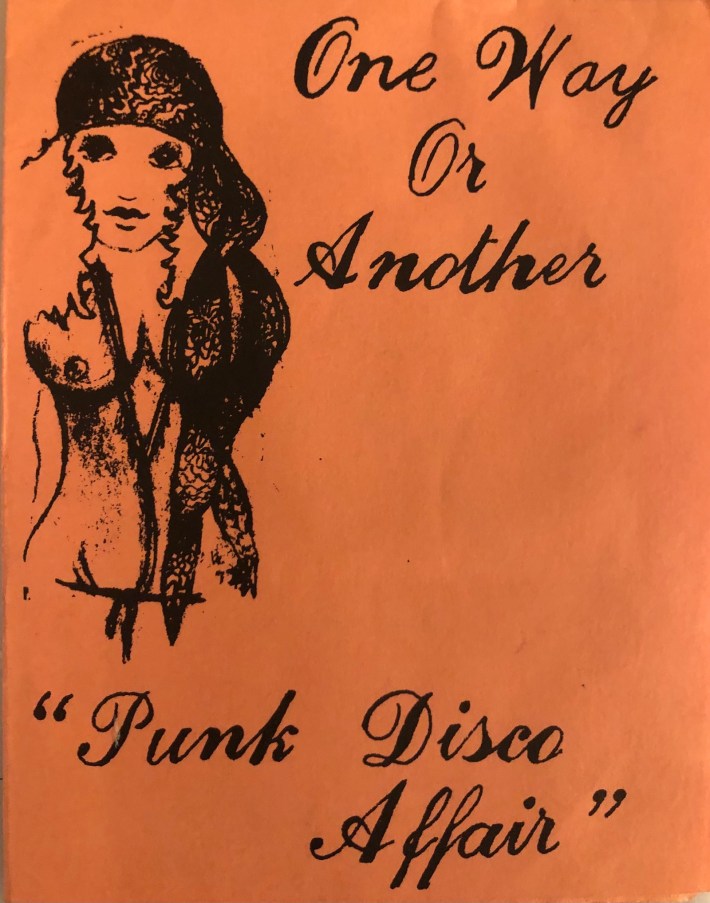

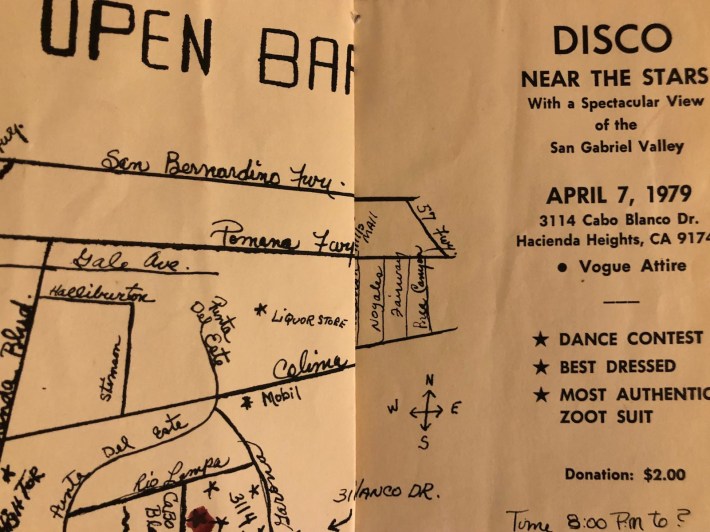

They chased their favorite DJs at clubs and backyard parties who imported hard-to-find European and Canadian disco records with a strong electronic dance feel. Party flyers requested ever-changing dress codes to match the changing musical styles, like “tropical, vogue, jet-set attire” for one 1979 party and “Dressy dress” for a Montebello shindig. One, for a 1980 party at the Monterey Park, Legion said the attire was “Western (a nod to John Travolta in Urban Cowboy, one DJ said)” “Punk” or “new wave.” There was even a competition for the “Best Zoot Suit” at another disco party, as style came back into vogue with the debut of Luis Valdez’s eponymous play in 1979.

Mario “Vinde” and other Eastside disco fans quickly point out that the teenage disco music and fashion were “not like Saturday Night Fever.” Another veteran Chicano DJ called the Bee Gees music “disco for the Midwest.”

These backyard parties were an evolution from 60s kickbacks, said Mario Vinde, who said he remembers his older brother’s car club in East L.A. having backyard fiestas with live bands and records. “The difference was ...we put (on) a truly professional sound system and light show like none other,” remembered the former DJ.

Promotional cliques, also called crews, organized these disco get-togethers. There was something “really corny” about their names, said Guerrero, who recalled clique names like “The Gentlemen of Stardust,” “The Gentlemen of the Disco,” and “The Gentlemen of Pegasus.” The latter was made of the Cerda brothers and was one of the most popular DJ groups of the scene, along with Vinde Champagne, Audio Climax, and Face to Face.

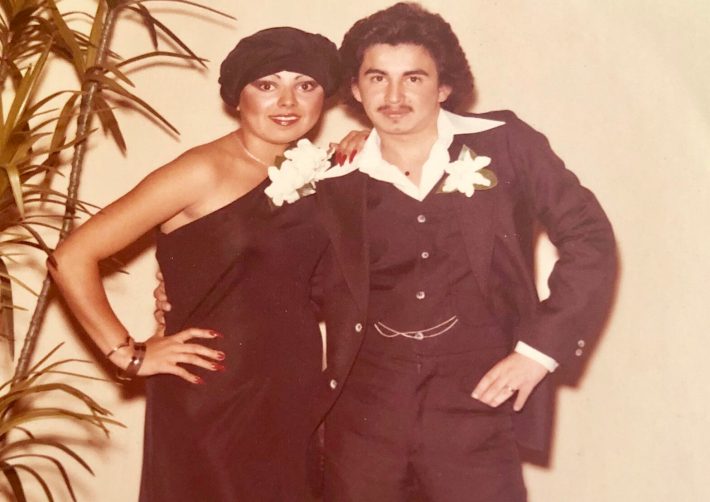

“We called the trendsetters ‘Hollywoods’ or ‘Vogueras,’” remembered Theresa Montalvo (née Garcia), my mother. She grew up in Hacienda Heights and attended backyard disco parties as a teenager at Glen Wilson High School.

The competition between the cliques and their recruited DJs was fierce because not only was it a dance party, it was a business opportunity for working-class Chicano teens. Cliques planned party logistics, secured the DJ and the venue, managed event promotion, and collected donations at the door.

“It was very much a sense of entrepreneurship,” said Guerrero.

“They were thrown out.”

But even as teenage backyard parties embraced the underground, the so-called “old disco” scene raged across the Eastside.The Black Angus at the Puente Hills Mall or The Red Onion in West Covina hired DJs and opened up dance floors after dinner service. Montebello’s Beverly Bowl had the Masquerade Room bar tucked inside, while Montebello’s restaurant bar Brandi’s turned their parking lot into a dance floor at night. The Great Gatsby in El Sereno was a local favorite, as was Shout! and the Turning Point in West Covina.

Monterey Park’s Polynesian-themed restaurant, Tiki’s, turned into a wild disco at night. Some locals remember even Jack LaLanne Fitness Centers turned into discos after the gym rats cleared out for the evening. Boomer disco bunnies across the Eastside still rave about Circus Disco, a Hollywood institution that was an essential space for the Latinx LGBTQ community.

The Eastside gay community was at the “forefront of a cultural wave,” said Guerrero, and was central to the backyard party scene. As the leaders in the latest disco dances, music, fashion, and artists. “The gay community had it going on,” he said.

For Rojas, who was part of the 1970s queer Chicano youth movement, the backyard parties offered a “comfortable” space to be queer on the Eastside—and breakaway from the prevalent machismo and gang culture.

But openness and acceptance in the Chicano disco scene weren’t universal.

Wings nightclub in West Covina was where “the rich Latinos used to go,” recalled Cadena Audoma. “Paul Rodriguez used to go there all the time.” One night, she saw a group of gay Latino men on the Wings’ dance floor that she recognized from Circus Disco. “[They] were thrown out.”

“Obviously, our culture has never been really open and embracing of things like that,” lamented Guerrero, citing conservatism and Catholicism. “If they didn’t like gays or you looked too poor...your shoes or your car, whatever. You were totally judged.”

Still, there was a bigger anti-disco movement growing across the country.

In the late 1970s, disdain for low-quality commercial disco music, radio hosts—like Chicago’s Steve Dahl, who openly mocked the genre—and racist, homophobic attitudes fueled the anti-disco movement. The climax of the anti-disco movement was the infamous 1979 Disco Demolition Night at Chicago’s Comiskey Park, where White Sox attendees burned thousands of disco records after the game.

Locals disagreed on whether or not the event impacted East L.A.’s music scene.

Guerrero said he encountered the anti-disco sentiment in his daily life. “You had people in your own community, in your own neighborhood, and especially in school, who gave you the ‘disco sucks’ thing,” he said.

Disco was not the predominant scene, said Guerro, so fans had to deal with bullies—usually the jocks or people into “mainstream” music like “rock or The Doobie Brothers”—who would “beat you up or chase you or make fun of you,” said Guerrero.

Rojas suggested the rise of the HIV/AIDS epidemic and the rising acceptance of the LGBTQ community meant there was “no need to celebrate.”

Kings of the backyard scene

“There’s not really an understanding of the different kinds of subcultural scenes amongst Latino youth,” explained Chimatli, a blogger, who attended both disco and punk backyard parties growing up. “While punk may get a lot of credit for being a DIY scene, the disco scene of [the] the 1980s rivaled punk in its ‘let’s organize ourselves’ philosophy,” she wrote in 2010.

But the different music scenes didn’t always rival. Sometimes, they became unlikely bedfellows.

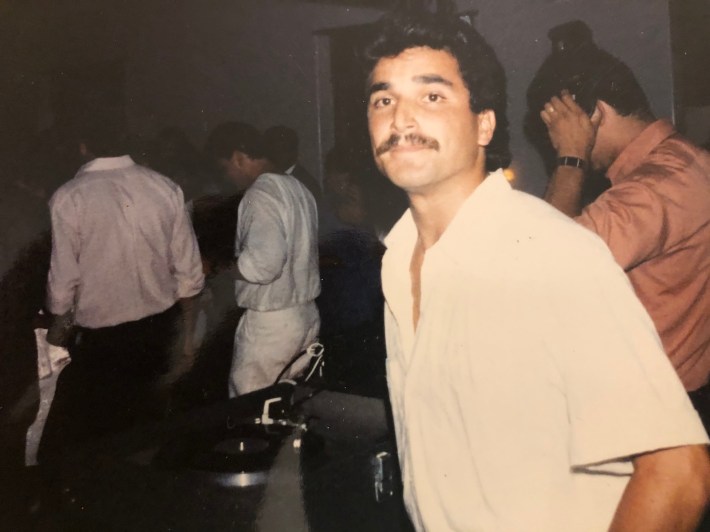

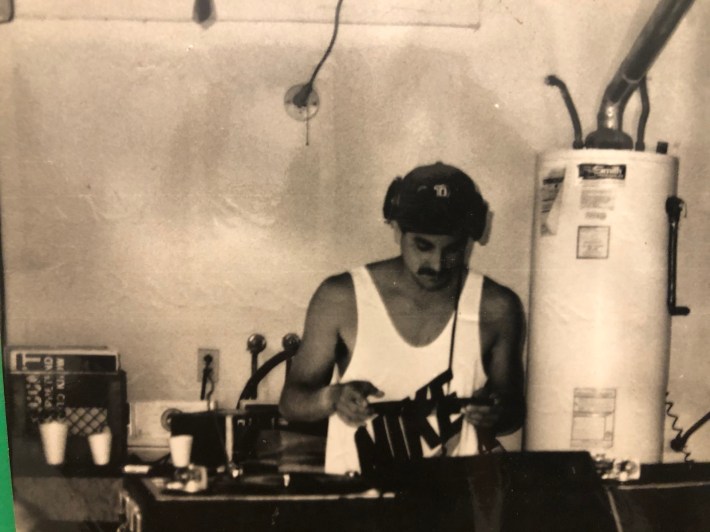

As a freshman at Cathedral High School, Ted Molina became a DJ in 1976. He played gigs nearly every weekend throughout his prep years and beyond as half of the duo Audio Climax. The young spinmasters formed one of the leading DJ groups of underground disco, famous for drawing people from nearly all of the Eastside’s music scenes.

Molina said part of their popularity was driven by their genre-blending of old and new disco sounds as well as his underground record collection.

“Our claim to fame was we didn’t just play disco, we broke away and started playing....K-ROQ music,” explained Molina. We differed from the other DJs that just played old disco.”

The blend of styles attracted an eclectic crowd.

“You would have people in their three-piece disco suits, and then you’d have somebody that looked like a punk rocker. And then, somebody that looks like Elvis back in the old days, or James Dean. It was really cool,” said Molina.

Canadian dance bands Tapps and Lime were his favorite groups to start the party. “There’s one song in particular that everybody played,” said Molina, referring to Lime’s 1982 hit, “Babe, We’re Gonna Love Tonight.” As soon as he put on the song, “Everybody would jump on the dance floor.”

After hours of dancing, partygoers flocked to the Denny’s on Garfield and Via Campo in Montebello. “You’d see, like, a hundred different people that were at the party right at Disco Denny’s,” recalls Molina. “Anybody that remembers that era, you say ‘Disco Denny’s,’ and they know where I'm talking about.”

Teenage DJs like Molina turned into local celebrities.

“People used to ask, ‘Where is the Audio party?’ We were number one for a time there,” remembered Molina. “It was like a cult. People followed us like you wouldn’t believe.”

Guerrero was one of these followers. “People would argue, literally during the week with each other,” he said. “Like ‘Who's the best?’ And ‘Who’s got the best parties?’ ‘The best music mixes?’”

While he never saw Audio Climax, Vinde Champagne, or Pegasus in person, Gerard Meraz knows them well. Meraz, a DJ, music scholar, and Cal State Northridge professor, has documented the 1970s “temporary discotheque” and 1980s backyard party scene. He also published a book on the rise of mobile DJs in 2011 titled “An Oral History of DJ Culture From East Los Angeles.”

“They are all a part of the first wave of Eastside mobile DJs,” he said. “They set a standard for sound and lights and DJing. Legends in many folks’ opinions.”

Last Night a DJ Saved My Life

Former Eastside teens said most of the disco parties were fun and positive experiences. “I rarely saw any problems... I think maybe because the cholos stayed far away from the disco thing,” said Guerrero.

Still, some parties attracted violence and danger.

One of Molina’s more colorful memories of his DJing career was of a shooting at a party on Dangler Street. Molina recalled that a pair of “homeboys” in a car chase ended up outside the party. One of the drivers crashed into the pole in front of the house and sought refuge in the backyard party. His pursuer followed close behind.

“The other homeboy started shooting at the very moment where ‘Rock Lobster’ said ‘Down, down,’” said Molina in disbelief. “Everybody went down. Consequently, nobody got hit.”

On another occasion, partygoers used his equipment as weapons in fights. “They would pick up our lights and smash them over people’s heads, and the next thing you know, the party was over,” he said.

Eventually, the police cracked down on these backyard parties. They threatened to confiscate expensive equipment, a considerable risk for cash-strapped teenage DJs. Sometimes, warring DJs and party crews snitched on rival parties in the hopes of attracting the partying teens to their events. Audio Climax transitioned away from backyard parties to event halls and performance venues throughout the 1980s.

Molina completed two years of USC’s Electrical Engineering program but then focused on his successful DJ and audiovisual career. “We were making too much money,” remembered Molina. “It took over my life.” Today, he still works in music, sound, and lighting for DJs, bands, and clubs, and he still DJs on occasion.

But his contemporary, Vinde Champagne, quit DJing in 1984. He recalled being so tired after years straight working weekends. He also admitted that FOMO had a role. “Everyone was having a good time except for me,” said Mario “Vinde.” “I missed out on so much.”

Still, he said the DJ world is kind of like the Mafia. “You can get in, but you could never get out,” said Mario “Vinde.” “Everyone treats me as if I was still a DJ.”

Disco Comeback?

Almost as quickly as it rose to the top, disco fell out of popularity in the mainstream music world.

But it retrenched underground. In 1980s East L.A., the backyard disco party scene evolved to embrace hi-NRG music, which blogger Chimatli affectionately calls “Chicano Disco.” Many Eastsiders that were teens in the 80s hear “disco” and think of the uptempo, synth-heavy dance sounds which define hi-NRG.

Joe Casillas, a veteran DJ who goes by Midnight Desire, said he thinks the 2000s has seen a resurgence in disco’s popularity.

“The kids that were 16 to 17 years old, now they’re in their 50s and 60s,” said Casillas, who pre-pandemic was hired to DJ a disco cruise. “They love the music and the memories.”

Some of the veteran DJs like Audio Climax, Pegasus, and Vinde Champagne still get together for occasional shows for their still-loyal fans.

Eastside Connection’s song, “Frisco Disco,” is still sampled by rappers and hip-hop artists today. Eastside singer-songwriter Nancy Sanchez recently covered the BeeGees in Spanish. Chicano Batman integrates disco and funk influences into their music.

New musical styles have adopted disco rhythms. “It’s funny because my son listens a lot to techno,” said Cadena Audoma. “I really like it because it reminds me of music from when I was growing up.”

Like many Eastsiders, Cadena Audoma said she misses her days of burning chancla on the dance floor. “I tell my son and our roommates, ‘Hey, my disco’s going on!’” she says with a laugh. “And I’ll put it on full blast at my house. I never stopped playing disco.”