[dropcap size=big]R[/dropcap]emember El Chupacabra? That mythical monstrous “goat-sucker” alien thing from the 1990s that left a trail of farm animal carnage in its wake? I remember a touristy “Chupacabra” T-shirt I used to wear a lot in high school that my grandparents brought back from San Felípe. The graphic illustrated a creature covered in dark gray spiny scales, grabbing air with its sharp claws, devil-red eyes, rat-like tail, and an ugly snarl that revealed jagged sharp teeth covered in blood. A mutilated goat carcass laid at the Chupacabra’s gnarly talons. On the back of the shirt was a list of “do and don’t” warnings in case you suddenly encountered the storied creature.

Even though it was first spotted in Puerto Rico, like many others growing up around Los Angeles and Orange County in the 1990s, I remember the Chupacabra as a Mexican urban legend, a menacing myth right up there with La Llorona, the “weeping woman” who trolls waterways looking for children to steal if they’re out playing near the water too late at night. At least that’s the version my uncles told my cousins and I to scare us during summer trips to Ensenada.

From Baja California through deep Tejas and down to Oaxaca, greater Mexican folklore is replete with these kinds of dark legends and myths. Folklorist Richard Dorson wrote in 1970 that Mexico was the first of the conquered “New World” lands “of consequence to feel the European conqueror’s heels.” Therefore, Mexican folklore is “a European narrative pattern imposed on Mexican Indian materials and presented as historical fact in a semiliterary context,” said the great Mexican chronicler, Américo Paredes.

“Mexican Indian materials” can include Meso American deities such as the Aztec plumed serpent god, Quetzalcoatl, who we’re told—presumably by Europeans—appeared to the Aztecs in the figure of Hernán Cortés, Mexico’s first Spanish invader. The myth of La Malinche persists. She was Mexico’s Indian “Eve” who betrayed her people by sleeping with Cortés and serving as his translator, thus facilitating the Spanish conquest of the Aztecs — the ultimate betrayal, according to the men have told this story over the centuries. Chicana feminists tell another version of the La Malinche myth.

Like all myths and folk legends around the world, Mexican myths, from Quetzalcoatl to La Llorona, act as repositories of historical, cultural, and popular memory. Sometimes they serve as creation or origin stories, other times as cautionary tales. But unlike the rest of the world, only México can boast a mythology of mezcal, the other agave spirit. Enter Mezcal El Silencio, a Los Angeles-based company and leading producer of the fine Oaxacan elixir with its own legendary origins.

[dropcap size=big]A[/dropcap] dismembered goddess. 400 drunken rabbits. Only one “stole the fire” to make mezcal.

El Silencio’s origin story evokes the ancient Oaxacan myths of the Alebrije, or renegade rabbit, and the deity Mayahuel, mother of the maguey plant. Its marketing campaign and promotional images feature the rabbit logo, a symbol of the origin story of mezcal and other agave spirits. As their version of the story goes, the goddess Mayahuel was chopped into pieces by her grandmother and fed back to earth. Those pieces birthed 400 rabbits—the agaves. Her story reminds me of another dismembered goddess, Coyolxauhqui, whose broken body became the moon and stars in Aztec mythology. In another version of the Mayahuel myth, the goddess “hooked up” with the god of pulque and made 400 agave rabbits who fed off their mother’s agave nectar and got drunk. El Silencio’s version of the 400 rabbit myth celebrates the one renegade rabbit, El Alebrije, who “stole the fire” from the gods to make mezcal.

Photo by Melissa Mora Hidalgo

Photo by Melissa Mora Hidalgo

I tasted my first copitas of El Silencio at El Speakeasy, the mezcal bar inside The Nixon Chops & Whiskey restaurant, now open in Uptown Whittier. Nixon’s executive chef – Top Chef alum Katsuji Tanabe of Mexico – and his general manager – Guadalajaran-born Lucy Zuzuárregui – proudly feature El Silencio mezcales on their cocktail menu. El Speakeasy is one of the few mezcal-centered cantinas on L.A.’s Eastside, and hopes to tap into the drinking public’s surging interest in Oaxaca’s native beverage.

“Mezcal is hot right now,” says Zuzuárregui, noting the spirit’s increasing appearance on cocktail menus, bar shelves, liquor stores, and dedicated cantinas in Los Angeles and across the country. “It’s an exciting time. Mezcal is smoky, a little sexier than tequila, and there’s so much history behind it.”

I order one each of El Silencio’s Joven (white label) and Espadín (black label). Zuzuárregui reaches first for the obsidian black bottle while bartender Vito Morales prepares an elaborate presentation for the proper drinking of Mezcal El Silencio. “Those are jicaras, traditional mezcal copitas,” Zuzuárregui says while pouring the Espadín into the carved half-shells ceremonially arranged for the purpose. For the white label Joven, bartender Morales prepares another set of jicaras. These ones come with the El Silencio rabbit carved on the outer shell like a delicate Easter huevo.

Photo by Melissa Mora Hidalgo

I take a copita and bring it carefully to my lips, savoring the sensations of this new drinking experience. I know better not to shoot mezcal. Sip it with care, respect. The mezcal looks like agua in those copitas, but I know it’s all agave fire about to prickle my palate before teasing it with smoky fig and maple syrup flavors that seduce my mouth, slide down my throat, and warm my belly. This is mezcal, handmade in Oaxaca by ancient decree and poured from a glass bottle with no worm. Not the cane sugar ‘apple juice’ kind mass produced somewhere in Mexico City that you can get at El Super in a plastic bottle for eight bucks.

[dropcap size=big]N[/dropcap]ow, about that rabbit.

The Alebrije featured on El Silencio’s logo, curled and spiny, looks a bit to me like that Chupacabra on my old T-shirt. The central figure behind the brand’s mezcales, El Alebrije (figured in black and white) represents the guiding mythology of El Silencio as envisioned by co-founder, Vicente Cisneros. How to tell this story and spread the gospel of El Silencio to the mezcal drinking masses?

“El Alebrije,” by Scott Minzy for Mezcal El Silencio

“El Alebrije,” by Scott Minzy for Mezcal El Silencio

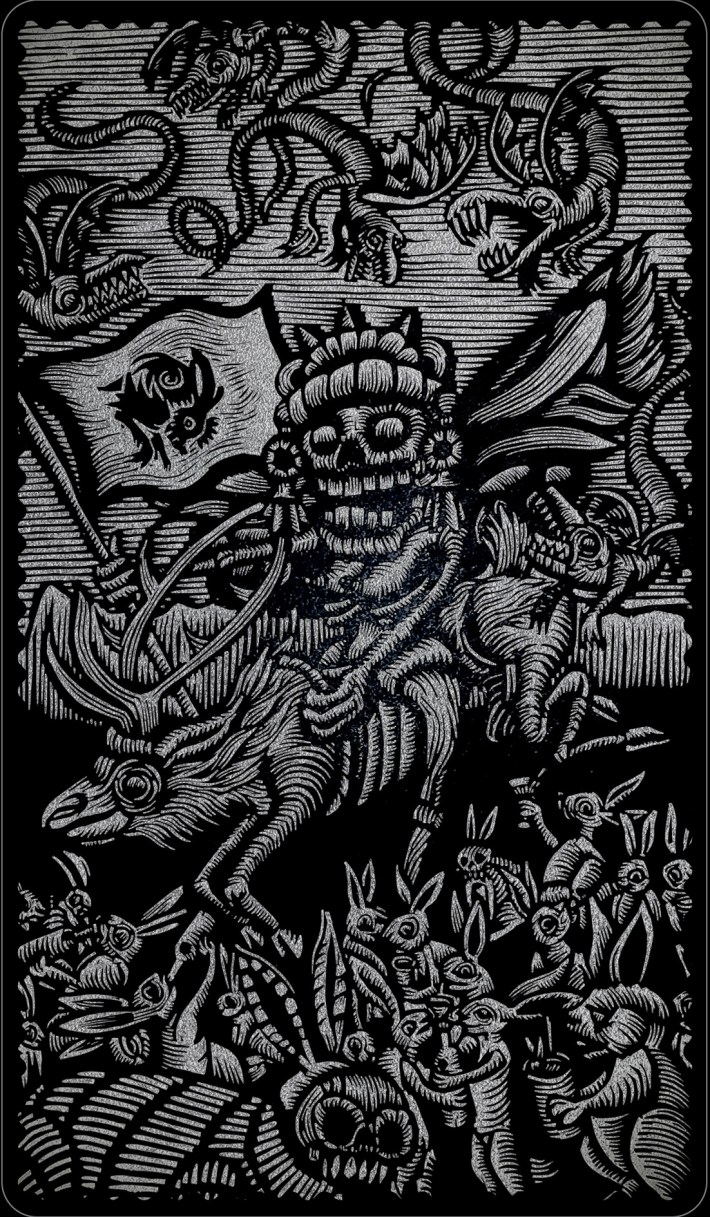

Enter artist Scott Minzy, a self-described “relief printmaker from deep within Stephen King’s Maine” tapped by Cisneros to design El Silencio’s promotional tarot cards. Each of the cards centers on a thematic element of ancient Oaxacan mezcal mythology, “reimagined through the lens of modern day popular culture,” as the brand puts it. Collectively, the tarot cards tell the origin story of Mezcal El Silencio through the figures associated with its myth-making and processing, including El Alebrije, the Goddess Mayahuel, the Harvester, the Smoke Pit, and Death.

We asked Minzy about his collaboration with Mezcal El Silencio and to discuss some of the myths behind these images.

LAT: El Silencio uses the “Alebrije,” or renegade white rabbit, as its logo and guiding storytelling device. Can you tell us how you came up with this image?

SM: Initially, I was approached by Vicente Cisneros about reinterpreting their logo as a relief print. Fleshing out the character and giving it more texture. It was soon evident that this was more than a logo redesign. He sent me a folder of about 60 images of everything from shells to different types of fur, snake skins, and claws dripping blood. Then when he talked about these characters, he wasn’t talking about imaginary creatures. He would talk in the present tense, as if they were really alive. I see it as a passion project for Vicente because he is heavily invested in the tradition, mythology, and storytelling surrounding these mezcaleros and their communities. Ultimately, he must have liked what I made because he asked me to take on this project.

So what is the myth of the Alebrije?

I see the Alebrije as a symbol for the ultimate in loyalty, dedication and sacrifice. He alone out of the 400 rabbits gave everything to steal the fire and bring it back for the greater good. As a result of his quest, he has been grotesquely transformed, so he covers himself in the fine trappings of other animals to, unsuccessfully, hide this fact. The hard shell of a conch protects his frail body, and the spikes keep enemies away. El Alebrije has the talons of an osprey to grip and hold on to the things he requires, the soft fur of a rabbit from his past life, the feathers of the owl who know all things that happen in the night. The horns and crown represent dignity and divinity, and lastly a single tear for the care free life he once led.

Your images evoke many artistic tropes, from ancient Mesoamerican indigenous codex drawings to Victorian-era and gothic illustrations. What was your process in creating these images? Where did you turn for research or inspiration?

I tend to see and process everything through the lens of my childhood: 80’s horror movies, comic books, skateboarding, late night radio dramas like Nightfall, and punk/hardcore music ethos. I’m also inspired by Ed Gorey, Rod Serling, Kara Walker, Wes Anderson, José Posada, Gahan Wilson, Henry Darger, VC Johnson - all people who created something out of nothing.

As part of our collaboration, Vicente and I would talk about everything under the sun. He would reference images of killer rabbits found in medieval illuminated manuscripts, then mention ancient Mayan sculptures and next, New Orleans funerary monuments. I bring to the conversation my love of Jack Kirby’s square handed super heroes and my obsession with Max Ernst’s book of collages Une semaine de bonté, where you find the Victorian/ Gothic influence.

You mention José Posada, whose work many people recognize around Día de los Muertos celebrations.

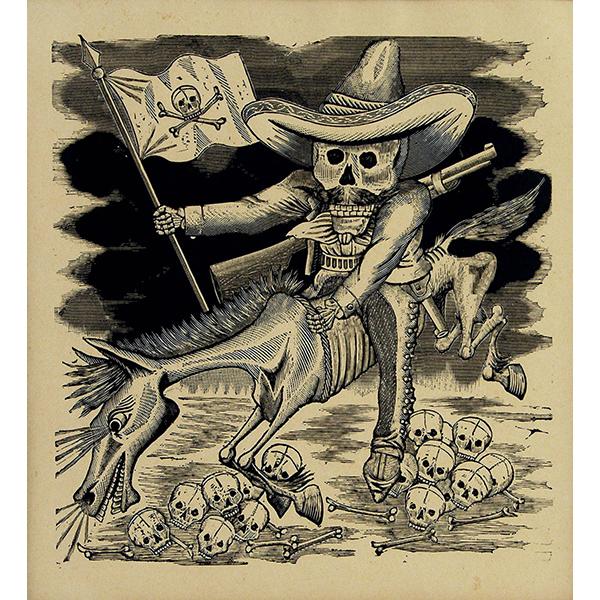

Yes. For me, the El Silencio “Death” tarot card is really an homage to Posada and his print Calavera Zapatista [c. 1910]. In this card, the traditional reaper is replaced with Itzpapalotl, the Aztec goddess of death, [or] the “obsidian butterfly.” In the El Silencio mythology, Itzpapalotl is a liberator who helps you to cut away things that are already dead in your heart, killing those things that are dragging you down and freeing you to follow your dreams. This immediately made me think of Calavera Zapatista, Posada’s playful allusion to literal liberators. I have borrowed the composition and theme but swapped out elements – the headdress, deer, wings, rabbits – to make it our story and at the same time pay tribute to the master Posada and the history of Mexico.

Posada, Calavera Zapatista (c. 1910) | “Death,” by Scott Minzy for MES

Are there more cards to come?

I've made more than 20 images for El Silencio and continue to work on more. It is ultimately up to El Silencio to decide what will be printed and when they will be released.

How do you like your mezcal?

Neat from a copita, of course.

[dropcap size=big]M[/dropcap]y copitas are empty, the orange rinds sucked dry of their juices and Tajín. Sitting in El Speakeasy, I remember fondly the first time I ever tried mezcal, about five years ago at Broken Spanish happy hour. I had just seen the Oaxacan-Mexican singer Lila Downs in concert.

“Goddess,” by Scott Minzy for MES

Zuzuárregui laughs when I tell her my crush on Lila Downs led me to my first mezcal. “Cuentan que en Oaxaca, se toman mezcal con café,” coos Downs in the opening lyric of her 2006 hit, “La Cumbia del Mole.” In other song, aptly titled “Mezcalito,” Downs gives a brinda, or toast, to “la Virgen de los Remedios De Santiago Mazatlán,” the patron saint of the “world capital of mezcal” in Oaxaca. In concerts, Down often dances around holding a bottle of mezcal on her head and drinking from it con ganas. Her songs and performances taught me my first lessons about the mystery drink before any of it ever crossed my lips.

I pay my bill and linger a bit inside El Speakeasy, satisfied from a good day of mezcal research and writing. I thank Zuzuárregui and Morales for their generosity, knowledge, and service. “Everyone knows about tequila,” says Zuzuárregui, “but I want to get people excited and educate them about mezcal.”

We can start with Mezcal El Silencio and the myth of the renegade rabbit. Go ahead. Chase the fire.

Visit El Silencio at their official website, or follow them on Instagram.