It took the mysterious illness of a punk icon to bind together a few scattershot supergroups and one of the most drooled-upon prospects in indie rock unification: Bud Gaugh and Eric Wilson, the two surviving members of Sublime, playing the band’s tunes live with Jakob Nowell, the son and spitting image of Bradley Nowell, the Sublime singer and frontman who was taken too soon by a heroin overdose at age 28 in 1995.

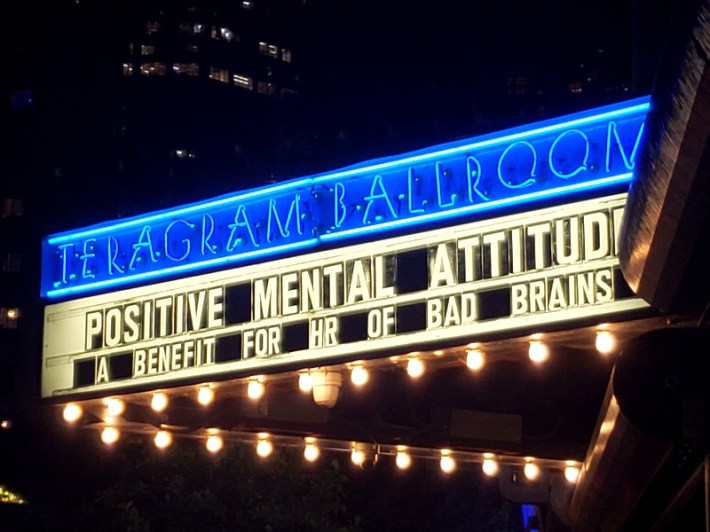

Rallying these Long Beach locals, as well as a crowd of a few hundred concertgoers, to Downtown’s Teragram Ballroom on Monday night lay a mission to raise funds to help cover medical costs for H.R. (Human Rights), the enormously influential lead singer behind Washington D.C.’s ferocious rastafari thrash band Bad Brains, and a cherished solo artist.

H.R. continues to struggle against an enigmatic medical disorder known as SUNCT Syndrome, characterized by cycles of impossibly intense, stabbing headaches that "Mama" Troy Dendekker, mother of Jakob, widow of Brad, would describe to the crowd as “100 times” worse than the pain of a migraine.

The condition has forced H.R. to stop touring, hitting him with the dual tragedy of mounting medical debt and an inability to make money on the road. In response, a battery of musical friends came together for the man, considered both friend, collaborator, and major mentor to all those assembled.

The show was kicked off with a DJ set by Beastie Boys collaborator Mario C before an introduction by Norwood Fisher, the mighty oak of a bass player behind Fishbone and an Angeleno who’s eternally at the core of L.A.’s heaviest jam sessions. Fisher, flanked by creative producer Kentyah Fraser and Dendekker, explained how they organized this show for H.R., who the bassist referred to, along with all of Bad Brains, as his “big brothers.”

Fisher recounted the seminal eighties afternoon when, while growing up at La Cienega and Cadillac, his friend and future bandmate Angeleo Moore came over and made him listen to the first Bad Brains record.

They simultaneously agreed that these were seriously bad motherfuckers behind that vinyl. To discover that the punk band was Black, dreadlocked, and also playing Reggae, was earth-shattering, endlessly influential, and validating for the eclectic, free, oddball music the duo would make with their own beloved funk-punk-ska-metal band.

Dendekker also remembered her first Bad Brains show in 1989 in LBC as a “life-changing” night.

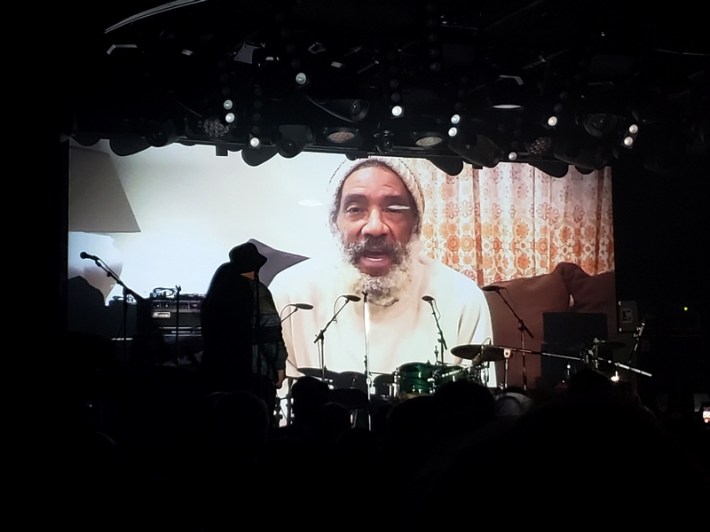

Their speeches were followed by brief video appearance made by H.R. himself, who was feeling too sick to attend the show as originally planned. He thanked the assembled, sending a message of love for everyone.

The music then got underway, starting with the steady heartbeat of Nyabinghi, as Trinidadian reggae singer Jah Faith led an acoustic group through a rendition of The Wailer’s “Rastaman Chant,” and endless crowd-assisted refrains of “there’s no night in Zion.”

Fisher then returned to the stage to revel in Bad Brains and H.R.’s reggae tunes with a full band, including Jamaican percussionist Santa Davis, a legendary musician who has backed too many famous roots reggae bands here to even get into, including performances on Bob Marley’s last three albums. Among the many musical Zelig moments in his career, Davis was injured while present during the robbery and murder of the late, great Peter Tosh.

On keyboards was Beastie Boys collaborator Mark “Money Mark” Ramos Nishita, while other musicians unknown to us tackled duties like melodica and lead guitar. Ras Israel Joseph I, who formerly replaced H.R. in Bad Brains, was on vocals, fully possessed with a Bad Brains spirit that could take him from silky melodies to guttural growls and high-pitched wails in a flash.

A touted appearance by London dancehall don Mad Lion didn’t materialize due to difficulty reaching the gig, while the rhythm section drove on mightily through a few dub-laced numbers Israel shared with Ras 1, a Long Beach artist known to Sublime fans for his work with Long Beach Dub-Allstars. Israel and Ras-1 exchanged turns chatting various Jamaican musical platitudes in the style of vintage DJs like I-Roy and Big Youth, the former coming correct, the latter maybe not so much.

Israel went solo to cover a few impassioned H.R. reggae ballads before being joined by Fishbone’s spark plug, the irresistible ball of light and energy known as Angelo Moore, who came out dressed like Helen Roper, had her mumu had been issued by the state pen (we could have sworn we’d just seen him decked out in a vintage three-piece Stymie suit and bowler hat in the lobby).

Comedian and former punk drummer Fred Armisen briefly hit the stage behind a kit to teach everyone “the history of punk drumming” in roughly three minutes, veering expertly from a typical Velvet underground beat to those found in genres typified by The Clash, Bad Brains, Fugazi, The Misfits, Sleater Kinney, and eventually Blink 182-style “happy punk,” all the while mocking and paying tribute with generic lyrics to match their styles.

Returning to the stage, Moore and Joseph exchanged honeyed harmonies on a version of Bad Brains’ “I Love I Jah,” in a really beautiful musical moment that would be exuberantly shattered as they ripped into a set of Bad Brains’ D.C. hardcore. For this set, the singers were joined by drummer Dave Lombardo, a hard-hitting co-founder of a small Huntington Park-born band known as Slayer, who was incredible to watch in such a stripped down local show.

Fishbone, who have played an untold number of shows with Bad Brains, may be the perfect band for living up to the proper batshit insanity of one their shows. Moore’s manic, bug-eyed attacks, ripping through rapidfire lyrics on the mic, was blistering, saturated with equal parts joy and ferocity.

The band ripped right out of the gate, taking on quintessential Bad Brains and H.R. blazers like “Pay to Come,” “Saling On,” “Banned in D.C.” “Just Because I’m Poor,” “I,” and “How Low Can a Punk Get” with aggression and skill. The band finished with the catchy thrash anthem “Attitude” off the band’s 1981 debut album and the 1983 Ric Ocasek-produced “Rock For Light.” The pit swirled and staggered to the approval of the band, and the 58-year-old Moore even took a dive off the stage.

At one point, nailing down the difficulty of replicating a Bad Brains track, Moore noted that only “a bipolar brain” could create music like this, saying that every Bad Brains song is really five different songs in one and also referring to the mental health struggles H.R. has supposedly contended with, undiagnosed, for decades.

Interstitial tunes by Michael Rose, Max Romeo, and Anthony B wove their way through the Teragram in between live sets, courtesy of a dedicated selector from New York’s Subatomic Sound System. The lull between the hardcore set and the next guests, the reborn Sublime, seemed interminable.

It’s been about 30 years since I last saw Sublime, a band that formed a significant part of the soundtrack to my Southern California teenagerdom, not too long before Nowell’s death. I had a greater tolerance for standing, staying awake, and crowds back then, including individuals with little general awareness of personal space.

Pressed ever closer to the stage in anticipation for the headliners, I made the mistake of starting a conversation with a visibly intoxicated guy in front of me about his Buffalo Bills hat. Leaning extremely close to my face and putting his weight on me, he pulled out his cellphone.

“This is me with Eric Wilson,” he breathed warmly just a few millimeters away from a full-on kiss, showing me a photo of himself with the Sublime bass player. “I saw him in Vegas. He’s always on mushrooms.”

Unable to move my feet or shoulders, I physically positioned my head away from his, subsequently entering the extreme facial proximity of a different creature. He looked like the wax-cast love-child of Jim Parsons and Toby Maguire, if they had turned into agents in The Matrix.

“What’s your name,” he asked with a wide smile that would be an asset in door-to-door Mormon proselytizing. Repeated attempts to adequately comprehend my weird first name followed, until he finally announced, “I’m Gavin!”

Sure enough, I looked down at his shirt to see a sticker adhering to his shirt reading: “Hello my name is Gavin,” not far above a roll of such “Hello” stickers on his hip. Gavin then proceeded to light a tremendously large joint.

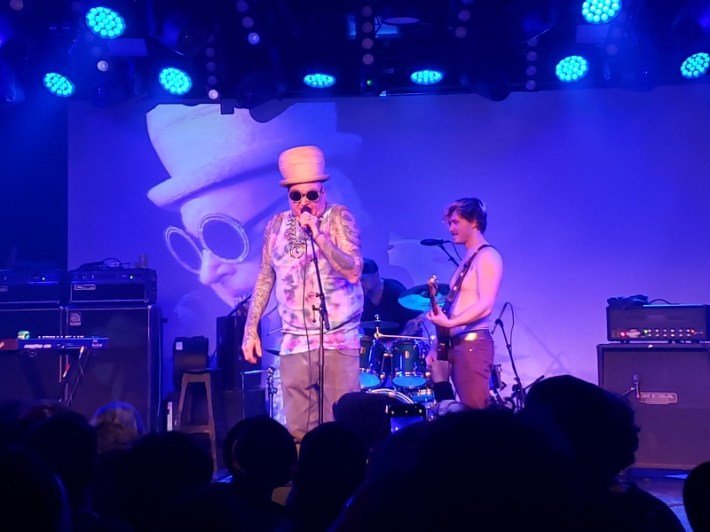

Finally, around 12:30 AM, it was Sublime-time. Even before the lights came up on the band, Jakob Nowell’s silhouette was hauntingly familiar, looking like a slightly more jacked ghost of his dad, from the way he held himself down to a surfer’s cut bearing shaggy bleached bangs.

In the last Sublime show I saw, following an acoustic set by the singer from Shine and a then-unknown Slightly Stoopid, the trio lumbered through their first few songs in a messy fog. Then, I don’t know, maybe something wore off, as the band suddenly clicked on “We’re Only Going To Die For Our Own Arrogance,” then turned out a blazing set of their punk, ska, rock, and hip-hop gumbo.

Jakob Nowell’s energy was dialed in from the start, his cleaner front instantly apparent. He came in screaming, “Los Angelessssss!”, his energy already beyond eleven. It was a marker of his preternatural professionalism and potential that he was able to not let that energy flag throughout the short set.

The band opened up with “April 29th, 1992,” the departed Nowell’s unapologetic narrative about participating in the looting of stores during the 1992 L.A. Rebellion. To handle the sound of Bradley’s surf-riding, shredding solos, the band had Long Beach Dub All-Stars' Trey Pangborn, one of the younger Nowell’s “uncles,” as he calls the members and associates of Sublime, handling lead guitar duty.

While there may have been just a little too much posing and cocksuredness on Nowell’s front for this crotchety, flabby, conceivably jealous Gen X’er (whipping off his shirt after the first song to declare, "now it's a Sublime show"), there’s no doubting that Nowell has the goods to front Sublime well into the future, his voice hitting accents and strides that sound just like his father without forcing anything; his pure enthusiasm for the music and the good fortune to be bringing it to people leading his high spirits.

The band played a short set of maybe 30-40 minutes or so, including deeper cuts like “Greatest Hits” fromthe Robbin’ In The Hood E.P. and “Burritos,” plus well-known Nowell song swans like “Santeria,” “The Wrong Way,” and “What I Got.” No Bad Brains were covered, but Nowell made a point to bring attention back to the reason we were all assembled: Helping H.R.

In a high point of Sublime’s set, Nowell, who is 28 (the same age the father who’d be unknown to him in the physical realm was when he died), asked the crowd if they liked what they were hearing. And if they’d like to hear more. In fact, whether they’d like to see this band continue down the road together. He agreed with the positive response, all but assuring the crowd this formulation of Sublime would be playing again soon.

While Nowell heads a cleaner, significantly less junked-up version of the band, Wilson still held the line of a 1990’s Long Beach hooligan bar band, hanging out with people in the crowd in a tall cartoon cap and occasionally taking the mic to utter streams of nonsense that essentially verified earlier rumors that dude is probably “always on mushrooms.”

At the show’s conclusion, Wilson stood there throwing (what looked like expensive) microphones down onto the stage as the rest of the band split, putting an end to the benefit show. Some things never change.

Overall, it was an epic night full of some of the city’s most charged talent, coming together to celebrate and support a hero to all. If you’re sorry you missed this chance to help a titan of punk rock, remember that you can still donate to help H.R. right here.