As certain as seeing the sunrise each morning, we can depend on avaricious entrepreneurs stealing the work of graffiti artists. L.A. TACO has touched upon such cases of plagiarism or outright theft concerning local artists, including Shark Toof, Shawn McKinney, Brandy Flower, and Aiko, in the past.

The latest painter to suffer the sting of big business burglary happens to be a major force in innovative West Coast vandalism: OG SLICK, née Richard P. Wyrgatsch II, the Hawaii-born graffiti artist who made his legend on L.A.’s walls starting in the mid-80s, and today is considered among the planet’s most influential graffiti artists to go from the gutter to the gallery.

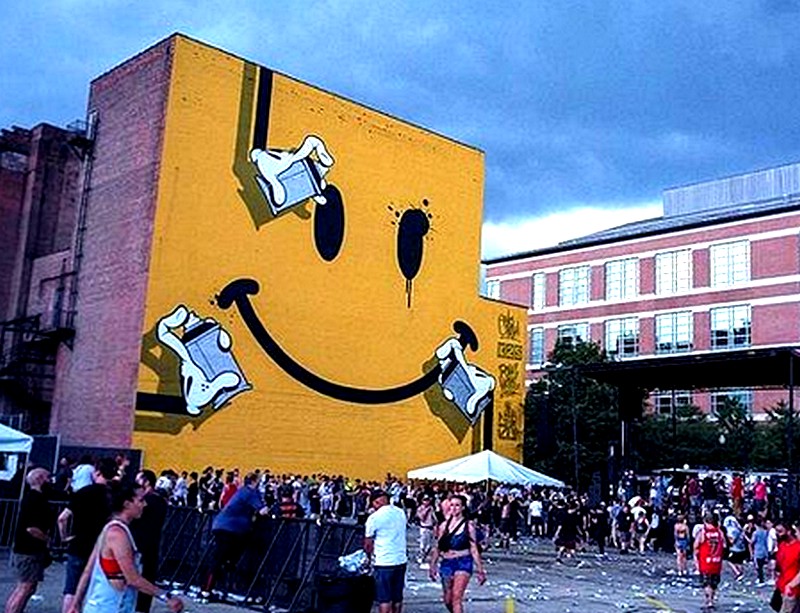

While it’s not completely uncommon to see SLICK’s infamous Mickey Mouse hands used by reverent aerosol artists in the graffiti game, a company based in Rhode Island has taken the symbol too far, putting a mural SLICK painted back in Worcester, Mass., on a Monopoly board comprised of local sites and attractions.

According to ArtNet News, Top Trumps USA is suing in a push to get a U.S. District Court in Massachusetts to validate what it claims is fair usage of a photo of SLICK's mural, which was created in Worcester (aka Woosta’) in 2018 for a local festival. SLICK’s piece was itself inspired by the work of another artist, Worcester-born Harry Ball, famous for creating the yellow smiley face icon, and features a massive smiley face being spray-painted by three gloved Mickey hands, themselves the original design of some dude with the ridiculous name of Walt Disney.

Top Trumps, which has a license from Monopoly to independently make such “niche” editions of the board game, included an image of the mural in the spot traditionally held by St. Charles Place in its 2020 version, as well as in the center of the board and on its box cover. When SLICK saw the game, he was (metaphorically) like, “Hold up! Do Not Pass Go, motherfuckers!”

Which is to say, he reportedly accused both the company and Hasbro of copyright infringement and got his lawyer, L.A.’s own Jeff Gluck, involved. Top Trumps, which doesn’t appear to have cleared the inclusion first, but denies infringing on anyone’s copyright, offered to switch out the photo in future editions. Meanwhile, Gluck has apparently tried to settle the matter outside of court.

Top Trumps says Gluck, who has an esteemed reputation for helping artists in these situations, be they between corporate entities or other artists, allegedly continued pressing for a six-figure licensing fee and “all” profits from the game’s sale, noting the artist’s profusion of gallery shows and merchandise sales.

So now the company’s taking it to the courts, suing SLICK and Gluck, and petitioning the legal system to try and get them off their back from making what it suggests are “baseless claims.”

Gluck won’t budge, though, telling Artnet, “They have refused to drop the lawsuit, and we plan to respond and proceed to trial on the merits.”

Now, surprise, we’re not legal scholars here or anything. And we are genetically predisposed to taking the artist’s side in cases where their work may be used in making a sale for someone else.

But the outcome in the SLICK vs. Top Trump’s beef may eventually come down to whether an image of SLICK art, featured in a very public place, is considered to belong to the game company, the person who took it on their behalf, or to the artist who created the image in the photograph.

While a photograph itself is generally considered the legal property of the person who took it, regardless of who owns the camera or cellphone taking it, determining factors are likely to include whether or not the featured artwork itself is copywritten, exists in the public domain, or is considered a public attraction freely shootable by anyone who cares to.

The frequency of the image appearing in the game, on its box cover, and in any potential marketing materials will also be key points. Also potentially pertinent is whether or not the smiley face and Mickey hand motifs themselves, originally the work of other artists, can be considered as belonging to one particular artist or not.

In one way, the situation brings to mind what artist Shepard Fairey experienced through something like the reverse of this controversy, in which he made a popular painting from studying a copywritten A.P. photograph of President Obama and was eventually sued for copyright infringement and fined $25,000 for destroying evidence related to the case.

In this case, too, it looks like it will be up to the courts to decide who deserves the right to get paid for the image of another person's image, itself originally remixed from two other people’s images.

We’ll keep you posted when we hear more.