Food has the power to unite us but also divide us. Nowhere is this truth more palpable than in gentrifying neighborhoods like Highland Park, where newer restaurants on Figueroa Street, like Hippo and Cafe Birdie, tend to attract a wealthier, whiter demographic than O.G. favorites like Follieros, Chicos, and Las Cazuelas.

Higher-end restaurants are often seen as a precursor to greater gentrification, a process research and advocacy nonprofit Studio ATAO define as: “when a previously dis-invested neighborhood changes significantly due to investment and development in the area, often in conjunction with the arrival of more affluent residents.”

While everyone feels differently about gentrification, depending on their political views and individual privileges, the undeniable problem is that not everyone benefits equally from increased investment and sudden media and developer interest in a neighborhood. Those who’ve lived in Highland Park for generations agree it’s safer than it was in the 90s when gang activity was at its peak, but it’s no longer affordable for many—or even recognizable in certain respects.

“I think prices [at newer restaurants] are intimidating, and they’re not very welcoming to the locals,” said Jammy Torres, 36, the owner of Hadassah Hair Studio on York Boulevard. A Franklin High School graduate, Torres grew up in the neighborhood and remembers seeing a local fruit vendor gunned down in front of her elementary school on Monte Vista Street around 1993 when she said it was a dangerous place to live. She opened her hair salon in 2012 and moved six years later to Chatsworth, where she could afford to rent a house.

Years later, there are still affordable places to eat and shop for groceries in Highland Park, including Food 4 Less, which now has a decent organic produce section, the cleanest Super A Foods on earth, and smaller, quainter stores like Feli-Market Market, which manages to squeeze everything from tomatillos to birthday cakes into their tiny corner on Figueroa and Avenue 54. The taco scene is notable, with two-time Taco Madness winner Villa’s Tacos still slangin’ distinctive blue corn-tortilla tacos out of this hood. In fact, owner Victor Villa is soon opening up a brick-and-mortar in a yet-to-be-determined location after a $100,000 grant from Estrella Jalisco beer.

However, the neighborhood’s increasing popularity has also drawn in developers and raised home prices. While gentrification may bring about more racial diversity in some places, it rarely creates economic diversity. When it comes to the food and drink scene, heavily-invested ventures put the spotlight on a neighborhood that otherwise might have flown under the radar. These restaurants and bars have the power to draw diners from all over the city into neighborhoods they wouldn’t normally venture into through good reviews, successful chefs and mixologists, and trendy ambiance from the minds of pricey design firms.

While high ceilings, open rafters, and pendant lights are nice to look at, in places like Highland Park, they too often come with consequences. Feeling like an outsider in your own ‘hood is wrong, but is the right answer to take it out on restaurants that may or may not have your budget or palate in mind? What about the fast food chains that many low-income families rely on that are contributing to our community’s health problems with menu items that aren’t conducive to a healthy mind, body, or spirit?

Knowing this, is it really so cool for "trendy" restaurants to contribute to this type of economic violence – knowingly or unknowingly—in a neighborhood they've found a low bar of entry for rent in?

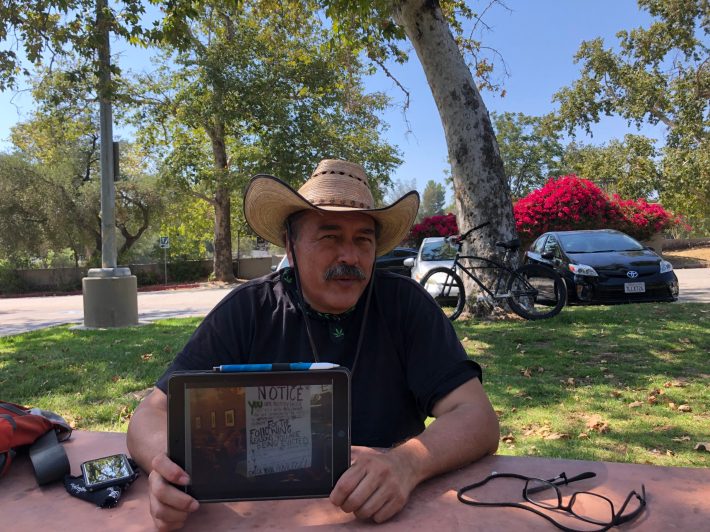

John Urquiza knows how it feels to be facing displacement from a neighborhood he long called home. In 2008, the El Sereno native was in foreclosure on his Eagle Rock duplex. A former advertising art director and designer, he said he was privileged to have access to resources that kept him housed. He worked at the Highland Park Winter Shelter for three years and met folks who weren’t as lucky. He’s been on the frontlines of the war against gentrification ever since.

In 2011, as the artist in residence at Avenue 50, Urquiza taught photography and formed Sin Turistas, a collective that captured stories and photographs examining the effects of gentrification on their neighborhood. He collaborated with the Northeast Los Angeles Alliance in 2012 and has been documenting their tenants’ rights and anti-gentrification protests, including the first in 2014 when they posted faux eviction notices on businesses such as Cafe de Leche, Donut Friend, and The York for not being affordable and failing to acknowledge the displacement of locals.

What really radicalized him was in 2015, a year Urquiza considers the biggest gentrification casualty in Highland Park. After witnessing police sweep 75 encampments along the Arroyo Seco bike path, he watched as nearly 60 working-class Latino families he and North East Los Angeles Alliance had previously mobilized to keep housed were evicted after a developer named Gelena Wasserman bought the Marmion Royal apartment complex.

“I’ll tell you right off the bat, gentrification is a violent act,” said Urquiza, sitting on a park bench in Hermon Park. His bike leans on a glistening sycamore tree behind him as Buena Vista Social Clubs softly creeps out of a speaker affixed to his handlebars. A tall, burly brown man with a salt and pepper mustache, he’s usually found sporting a straw hat and black “Save the El Sereno Hills” T-shirt. “Investment destabilizes communities unless it's an investment for the entire community.”

Dunsmoor’s biggest mistake may have been calling their food “American Heritage Cookery,” a slap in the face to the largely Latino and Filipino community. Protesters spray-painted “Gentrification Is Genocide” on the window on opening day...

The photojournalist, educator, and organizer teaches classes on gentrification at Occidental College and also gives talks in the community on the history of displacement in and around NELA, paying tribute to Chinatown and the three barrios buried beneath Dodger Stadium: La Loma, Bishop, and Palo Verde, from which my own family descends.

Through a series of photos, maps, and timelines, he acknowledges the first people of this land–the Tongva or Kizh, depending on who you talk to–and educates folks on the economic inequities of gentrification. In 2011 he was displaced from the studio he worked out of above Cafe de Leche when a Latina owner started managing her parents’ property and increased his rent by 300%.

“She displaced me and every other Brown person in that building,” said Urquiza, who only supports Cafe de Leche out of all the new spots in Highland Park because he prefers their espresso.

Urquiza has recently been covering the controversial protests at Dunsmoor, a new restaurant that opened in Glassell Park in late June from Georgia-born chef Brian Dunsmoor. Dunsmoor lives in Pasadena, and restaurant partner Taylor Parsons, lives in Northeast L.A.

Parsons is married to Home State owner Briana Valdez. Urquiza says Valdez tried to talk to protesters at a recent action, but ended up peeling out in her truck when she wasn’t being heard. Dunsmoor’s biggest mistake may have been calling their food “American Heritage Cookery,” a slap in the face to the largely Latino and Filipino community. Protesters spray-painted “Gentrification Is Genocide” on the window on opening day and posted “No Highland Park v.2.0” online. They carried signs that said, “No to gentry restaurants!” and were outraged by the $23 green lentils (which have since been reduced to $13).

On the other side, there are residents who think neighborhood activists are barking up the wrong tree.

“Why aren’t you protesting the people who flip houses in your neighborhood?” said Melissa Morales, 43, who was verbally attacked by protesters after eating at Dunsmoor with her husband—who is Black and grew up in the Jordan Downs projects in Watts—and their friends, a Latina couple. “Those are the people ruining our neighborhoods. They're the problem. They're the gentrifiers.”

Morales grew up down the street from Dunsmoor on the border of Eagle Rock and Glassell Park, where her parents still live. She couldn’t afford to buy in the area when she and her sister were looking in 2016 and settled on a duplex in Alhambra. She’s just as outraged as protesters about gentrifiers making it impossible to live in certain neighborhoods but thinks harassing diners is a waste of time.

“They shoved a camera in my husband’s face and called him a sellout,” said Morales, who said she was also fat-shamed by protesters. “They were shouting obscenities at people and being very degrading and accusatory. This is my land. I've lived here my whole life. I've paid property taxes. I've gone to school here. My father worked to plant roots, and I want to make our tree bigger in this neighborhood. Because of gentrification, I can't. I don't believe this is gentrification on the part of the restaurant. That's on the greedy landlord.”

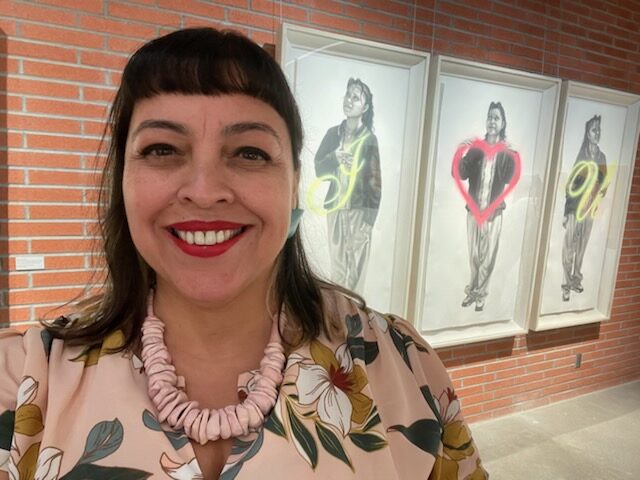

Nicole Macias agrees that folks have the right to eat at nice restaurants and was angry when some of her friends’ businesses landed on DefendNELA’s highly debated 2018 boycott list. She does, however, think diners should do their research and be conscious consumers. Born and raised in NELA, Macias, 33, has deep roots in L.A. Her grandfather, Jesus Hernandez, owned a restaurant and laundromat on Figueroa Street in Cypress Park, but his claim to fame was bringing the burro to Olvera Street, which her family still runs along with Mexican gift shop Hernandez Curio. She spent much of her childhood running around the birthplace of L.A. with her cousin, singer Marisol "La Marisoul" Hernandez of La Santa Cecilia.

Macias’s blog, Salsa on the Side, is an ode to the frustration she felt when customers requested “salsa on the side” of the chilaquiles they sometimes referred to as “breakfast nachos.”

Macias lived on Avenue 50 in Highland Park with her mom and brothers before moving to more affordable Central California for high school. She returned to the neighborhood in 2007 and started a job waitressing at the Highland Cafe when it first opened in 2012. Owned by Glassell Park native Arnie Miller, who is half-Mexican, half-German, it was here that she honed her social skills, befriended cafe regulars like Mi Vida owner Noelle Reyes, and became the face of this restaurant at the dawn of the neighborhood’s gentrification.

“When I worked at the cafe, people would come in and be like, ‘We just bought this house on the street, but man, the neighborhood’s not that great,’ Macias said. “I was like, ‘Wow. I can't believe people are moving into this neighborhood with that mentality.”

Macias’s blog, Salsa on the Side, is an ode to the frustration she felt when customers requested “salsa on the side” of the chilaquiles they sometimes referred to as “breakfast nachos.”

“My boss was great. He was always giving back to the community, so it was hard,” she said. “He would pull me aside and be like, ‘Nicole, we get a lot of complaints that you're rolling your eyes at customers.’ I'm like, ‘Well, they're acting stupid. I don't know what to say. I'm biting my tongue.’”

Her waitressing days behind her, Macias is now a copywriter at Everlane, a conscious clothing company based in San Francisco with a creative studio in L.A., and also runs a free clothing swap called Radical Clothes Swap with three other women. She lived in the only place she could afford in Highland Park, a studio in a notoriously dangerous brick building tucked behind a fourplex on Avenue 50 near Figueroa Street. That’s where her boyfriend, who’s Black, was held at gunpoint one night while getting something out of his car.

Another evening, a white teacher friend who was staying with her was nearly stabbed getting off the Gold Line’s Southwest Museum station. She recently moved in with her boyfriend in Glendale but hopes to one day be able to afford a house back in her old ‘hood.

“A lot of us come from poor and working-class families,” said Macias, seated outside Gloria’s Cuisine LA, a self-proclaimed “elevated” Latin American restaurant on Avenue 50 owned by Marco Rodriguez, a native of Chiapas, Mexico. She used to work out of the restaurant when it first opened in 2016 and was initially empty. Now people flock here for the amazing chilaquiles and café de olla. “We’ve reached a point where we don't have to live like that anymore. We have the right to treat ourselves to a nice restaurant.”

Amara Kitchen owner Paola Guasp, 36, opened her ultra-healthy restaurant, which offers vegan and vegetarian items, in 2014 with a friend, but without the help of investors. Born to parents who struggled with drug addiction, she lived in Chile with her father’s family from the age of eight months to five years old, when she moved to Van Nuys to live with her mom. Guasp was a nanny with some savings when she opened her restaurant on Avenue 64 in Highland Park. Diners swarm to the charcoal grey-colored corner spot with trippy art painted on the outside for high protein, low carb fixes like poached eggs with mixed greens, sweet potatoes, avocado topped with pesto, beet purée, and purple cabbage with paleo bread. She sourced decor from Goodwill, had her uncle build the counters, and still uses benches donated from nearby high schools.

Guasp created the Come Together Bowl, a pay-what-you-want item made up of eggs, rice, and vegetables for the unhoused or folks on a budget who want to eat healthily, but don’t have the time and don't want to eat at the nearby McDonald’s. It’s been on the menu since they opened.

“I come from a low-income family,” said Guasp, who just gave birth to her first child. “I literally had my family tell me ese comida no es para nosotros (this food isn’t for us) when I first got into healthy eating.” After struggling with health problems, she switched up her diet and strongly believes food is medicine. She wants to share that with the community.

Guasp created the Come Together Bowl, a pay-what-you-want item made up of eggs, rice, and vegetables for the unhoused or folks on a budget who want to eat healthily, but don’t have the time and don't want to eat at the nearby McDonald’s. It’s been on the menu since they opened.

“I’m not gonna lie and say gentrification decimated me,” said Guasp, who opened a second location in Altadena in 2020 and heartier breakfast and lunch spot Ziv inside La Tropicana market in 2021. “Wealthier people are generally keen on healthy food trends. It's a privilege that I cook that food, and people who have money want to eat it.”

It’s a catch-22, though. Guasp said customers can be fussy and entitled, requesting things like three containers of maple syrup for free and always asking for sauteed kale, which isn’t on the menu. “In-N-Out has onions,” she laughs. “You’re not gonna ask if they can pickle them.”

Another vegan restaurant in Highland Park, Kitchen Mouse—which opened in 2012—has received a sizable amount of anti-gentrification hate. During the 2020 uprising, someone tagged “Whites Only” on their storefront with a Sharpie. Owner Erica Daking was at home when she first heard about it and quickly had her staff remove it, but rumors spread online that it was left up for weeks. Sitting in the former Mr. Holmes Bakehouse she took over in February and now runs her bakery out of, she was scared and losing hair while under attack by an anti-gentrification Instagram account that encouraged followers to give her restaurant negative reviews on Yelp.

“I had an interview with a potential candidate for a job who was Black,” said Daking, who is originally from New York and has lived in L.A. since 2003. “He wrote to me and said, ‘I went to your Yelp page, and I want no part of your business.’ I thought, ‘This is getting out of control. It was really traumatizing. I didn’t want to hurt any more people.”

But the negativity hasn’t stopped Daking from expanding. She and her sister, who run Kitchen Mouse together, are currently gutting the 50-year-old former Yum Yum Donuts that sits next to Taco Fiesta. The new space will be a faster, walk-up version of Kitchen Mouse—and it too hasn’t gone without haters. Last October, someone tagged “Kitchen Rat is not welcome here” on the side of the building, where a Kitchen Mouse sign is painted.

“Yes, of course, there's privilege,” said Daking, who first started her catering business while making $9 an hour working at Nicole’s Market & Cafe in South Pasadena. She took on investors in exchange for half of her business.

“We see hospitality businesses as uniquely positioned to address gentrification from within the neighborhood’s borders.” - Jenny Dorsey

“I moved into a space and wasn't really thinking about the consequences,” she said. “I just needed a place to put a kitchen. There was an empty storefront in the neighborhood where I live. I rented it, built a kitchen, and opened a tiny little restaurant with 12 seats. I didn’t expect to do well or have any impact.” The building has since been purchased three times while her rent has quadrupled in the last 10 years.

“We opened a business in a neighborhood where a lot of people feel threatened,” said Daking, who donates food and gift cards to local schools, puts out a box every year for a toy drive for the Arroyo Vista Family Health Center, and buys an ad in the newsletter for the annual NELA Christmas Parade. She recently donated gift cards and shoes for a back-to-school drive for homeless students. “One of my beloved employees grew up here, went to Franklin, and can't afford to live in the neighborhood. It's a bummer.”

Her experience mirrors that of many other restaurant owners across the city, who are still reeling from a devastating pandemic. Some were able to figure out the puzzle that was the PPP (Paycheck Protection Program) loan application, but maintaining payroll still proved nearly impossible. The unclear mask mandates from the state also haven’t helped promote consistent business.

Opening up a restaurant in this climate is not for the weak, but Gus Palaez, 41, was down for the challenge. He is the grandson of Gustavo and Irene Montes, the founders of the famed Highland Park restaurant El Arco Iris, which opened in 1964 and closed in 2017. Palaez wants to continue his family’s legacy and opened El Arco Lincoln Heights in May with chef Juan Montoya, who worked his magic in the original El Arco Iris kitchen for 28 years. Still serving “your grandma’s recipes,” people drive hours for the chile verde, wet burritos, and huevos rancheros. Palaez wanted to open the business in Highland Park but couldn’t afford the rent.

“People who own homes are ecstatic because their property value went up, but people who rent are devastated because their rents have tripled,” said Palaez, who grew up on Avenue 47 and York Boulevard, and now lives in Downey with his wife and children. “When they get a new donut shop that's trendy, and the donut costs $7, people don't mind eating it, and they love it, but that’s part of gentrification, that’s part of rents going up.”

Local educators also feel the effects of gentrification. Angelina Saez was born and raised in Echo Park and Silver Lake. She moved to Highland Park in the late 90s and, in 2008, started the Dual Language program at Aldama Elementary School, which attracts many of the white newcomers in the area who understand the benefits of being bilingual. The mainstream, English-only program has always been, ironically, mostly Latino.

A published poet and children's book author who hosted La Palabra Poetry readings at Avenue 50 Studio, Saez retired after 23 years of teaching this past June and recently moved to Boyle Heights. After getting divorced, she sold her home in Highland Park in 2015. She tends to move out of gentrifying neighborhoods.

“When restaurants and shops took over York, I moved to Hermon,” said Saenz, 50, who taught her students about Dolores Huerta, native peoples, and Black inventors. “When they took over Figueroa, I started hanging out around Huntington Drive. I know there are contradictions, and it’s very nuanced. I can only talk about the loss I feel when neighbors, shops, and restaurants I hold dear to my heart close. Then a new business opens, charges a shitload of money, and doesn’t feel welcome. But not everyone from the old neighborhood feels this way and has told me to stop talking shit, so it’s complicated.”

“Lowering prices is the only thing I can think of to make places more welcoming...” -Yesenia Cornejo

Saenz admits the noodles at Joy are “bomb” and goes to Hippo because her parents give her gift cards, but she mostly prefers old-school places like Cocoa’s, El Huarache Azteca, Troy Burgers, and Penny’s on York. On Figueroa, she sticks to Las Cazuelas, Antigua Bread, El Pescador, Folliero’s, Delicia’s Panadería, Feli-Mex, and Chico’s. She misses Elsa’s Bakery the most. The panadería was a mainstay on York Boulevard for nearly 40 years, and when new owners took it over in 2013, they kept the same pan dulce baker and hired East L.A.-based Barrio Planners to redesign the space with raza in mind, much like how Nativo and Pocha LA keep things gente today.

This ongoing tension for restaurant owners grappling with the effects of gentrification is something Studio ATAO noticed often went ignored in mainstream food and beverage coverage, and wanted to pay special attention to. The nonprofit launched an initiative called The Neighborhood’s Table with the goal of creating a responsible and actionable framework for business owners and workers to work alongside community members to combat displacement and invest sustainably in the neighborhood. This year, their focus is on L.A. and NYC.

“We see hospitality businesses as uniquely positioned to address gentrification from within the neighborhood’s borders,” said Jenny Dorsey, executive director of Studio ATAO.

The nonprofit’s gentrification primer breaks down the systemic issue that is gentrification and includes some initial ideas for business owners to be more inclusive–such as accepting cash, having a stash of water bottles, menstrual products, and Naloxone (a medicine that rapidly reverses opioid overdoses), as well as accepting EBT, displaying signs of support for the undocumented community, and donating to local organizations. Their forthcoming toolkit will feature even more detailed suggestions alongside case studies of hospitality businesses already doing this type of community-focused work across the U.S.

Highland Park native Yesenia Cornejo, 50, takes it beyond businesses and thinks the government needs to do more to help close the economic divide, providing more assistance for folks who have been hardest hit by the pandemic and housing crisis. L.A. City Council District 1’s new representative, Eunisses Hernandez, who is also from the neighborhood and ran on an anti-gentrification platform, may help bridge the divide. Cornejo strongly believes addressing inflation is the answer.

“Lowering prices is the only thing I can think of to make places more welcoming,” said Cornejo, who eats at Gloria’s, Fidel’s Pizza, and Folliero’s. “People will go if they can afford it. Everyone wants to try something new. People like the way new places look. It’s a different vibe. You want to be a part of that, but you can’t if you can’t afford it. It comes down to money.”

This L.A. TACO article was published in collaboration with Studio ATAO in an effort to change the way food media covers restaurants. Javier Cabral, the site's Editor, served as an advisor for their initiative, The Neighborhood’s Table.

_______________________________________

Author’s Note: As a POC and food lover, I’m torn eating at places most folks can’t afford. I’m lured in by chef (and fellow SGV native) Matt Molina’s perfectly al dente homemade pasta at Hippo, but it’s conflicting to look around and see very few diners who look like me. Those with dark skin like mine are often busting ass in the kitchen or bussing tables. It’s unsettling that the majority of diners at these newer, pricier restaurants are white, and I’m privileged to squeeze a seat at the table. As a fourth-generation Chicana, I can weave in and out of economic intersections seamlessly, but I also descend from a family that was perhaps one of the first businesses in L.A. to be displaced as a result of gentrification. My great grandparents moved to Palo Verde in 1913 and opened a store that sold homemade chorizo and pan dulce. They were evicted to build Dodger Stadium. The smell of chorizo sizzling in a pan reminds me of my great grandfather, who serenaded customers with his violin outside the store. Going to a Dodger game is just as conflicting as dining at a restaurant, which may indirectly be contributing to a local family’s displacement.