[dropcap size=big]H[/dropcap]ad Google Maps steered me wrong?

I walked about a half-mile from a Gold Line station and was directed left on South Pasadena Avenue. I saw what appeared to be a freeway exit with a “Do Not Enter” sign. This couldn't be right. I looked again as cars hit the breaks as if adjusting to street traffic speeds. Soon enough, two seniors headed left on foot down that road. They walked as if they knew where they were going. I followed their lead.

If California Department of Transportation had its way, this street would be part of the 710 freeway. Instead, cars speed passed CalTrans-owned properties, both vacant and inhabited. Artists Julia Tcharfas and Tim Ivison live in one of these houses, which also serves as the headquarters for their archival project Before Present. Right now, they're in the midst of a site-specific show about the freeway that changed this neighborhood.

RELATED: The Harsh Beauty and Banality of the 110-105 Interchange

Running from Long Beach to Alhambra, Interstate 710 displaced residents who lived in its path and angered communities situated along its intended route. It remains incomplete and continues to be a source of controversy. In "710," Before Present looks at the history of the freeway and how it impacted locals.

Preparation for what would become the 710 began in the 1930s. By 1964, the plan was to extend the newly-dubbed Long Beach Freeway into Pasadena. The effects of this decision hit communities immediately when hundreds of properties were purchased in L.A. neighborhood El Sereno, as well as the cities of Pasadena, South Pasadena, and Alhambra with the intent to demolish.

In 1968, Ivison’s grandmother moved into one of Pasadena's CalTrans-owned homes. Ivison, who grew up between Colorado and San Diego, recalls visiting her. “I knew that my grandmother got very frustrated trying to get things repaired. She always had a ‘No 710’ pin,” he says. “Only later did I find evidence of meeting notes and emails and things going back and forth, that she actually went to CalTrans tenants meetings, 710 meetings, that kind of thing. I don't know if she was ever a very active member, but she certainly went to meetings and kept up on what was happening.”

After his grandmother moved in 2015, Ivison and Tcharfas took over the lease. Ivison observed the neighborhood's quirks and issues. “I noticed very clearly what effect it had on the neighborhood, things that I never noticed when I visited my grandmother, like the condition of the sidewalks or the kind of feral landscape that it has created just by being neglected for so many decades, and how you can pick out on the block which houses belong to CalTrans and which ones don't.”

That helped spark the idea for the 710 archive.

Tcharfas says that they looked for “material history” of the 710’s impact on the neighborhood. “It wasn't clear if there was historical materials, visual materials, things that would make up an exhibition or an archive,” she explains. They reached out to long-running community group No 710 Action Committee and were connected with a woman who had a collection of related newspaper clippings dating back to the 1950s.

Tcharfas and Ivison present a story that shows the demise of the freeway boom.

They also came in contact with someone who runs a website dedicated to California's highways and brought in pieces like an atlas once owned by Caltrans with hand-drawn routes inside. They found books and videos and items like a hat with a tunnel and truck on top worn to protest a proposed 710 tunnel, as well as “No 710” buttons and other related items. Tcharfas used hi-res Google Earth images to present a visualization of the neighborhoods affected by the 710, which became part of a timeline built for the archive.

Tcharfas and Ivison present a story that shows the demise of the freeway boom. Los Angeles' freeways brought great changes, including the destruction of neighborhoods and displacement of residents. That happened with the 710 as well, but, this last portion of the intended freeway remains incomplete because it’s one of few instances where communities have, so far, been able to keep out the freeway.

"It's not just an eyesore. It's not just that district thing issue or a kind of NIMBYism. It's a health and safety issue. It's an environmental justice issue."

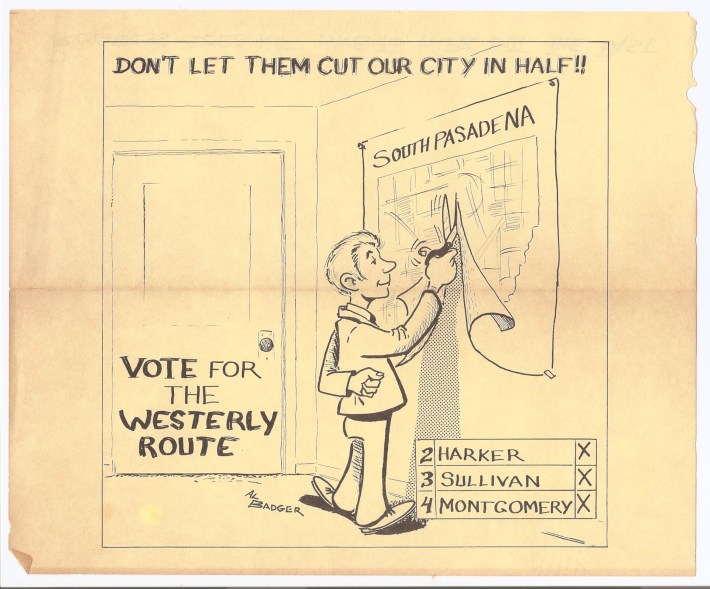

It starts with South Pasadena, who put up a fight against the 710 as the freeway would have physically split the city. “South Pasadena would have ceased to exist,” Ivison explains. “It would have been absorbed into its neighboring constituencies. So, in order for it to exist as a distinct city, they had to fight the project.”

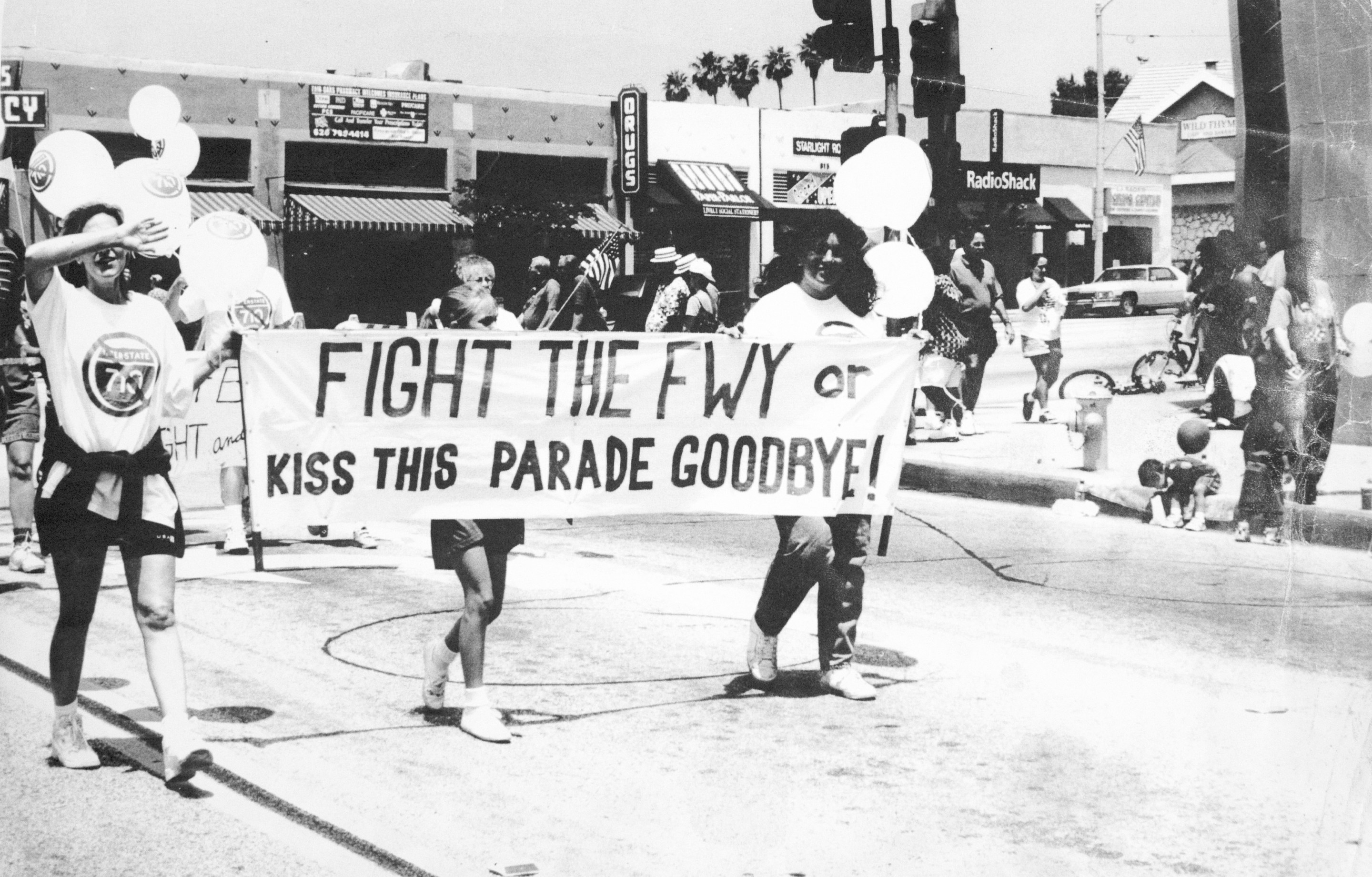

Freeways were popular — “a symbol of modernity," says Ivison — so South Pasadena didn't oppose the 710 so much as they did the route. When queries to have the route changed were rejected multiple times, they sued. "They filed different kinds of lawsuits," says Ivison. "They made it so that any local politician who wanted to get elected had to have a no 710 policy because they had the popular vote. They used both public and private money to fight the freeway."

Other local cities joined in the fight. So did organizations like the Sierra Club.

"They had a really interesting way of fighting," says Tcharfas. The tactics changed over time, incorporating issues from historic preservation to environmental justice. The latter concern has become most relevant today in light of studies showing the health issues related to living near freeways. Earlier this year, on the southern end of the 710, residents fought a proposed widening of the freeway in part on those grounds. Ivison points out now that the emphasis on environmental and health issues has become the big picture issue. "It's not just an eyesore. It's not just that district thing issue or a kind of NIMBYism," he says. "It's a health and safety issue. It's an environmental justice issue."

Before Present's "710" show ran at the home of Julia Tcharfas and Tim Ivison, where it was open by appointment. On July 4, the exhibition moves to the offices of South Pasadenan, where it will be open all day for the city's Festival of Balloons. The show will continue at the South Pasadenan offices through August 15. Hours are Mon-Fri, 10 am-6 pm.