This article was co-published with Crosstown.

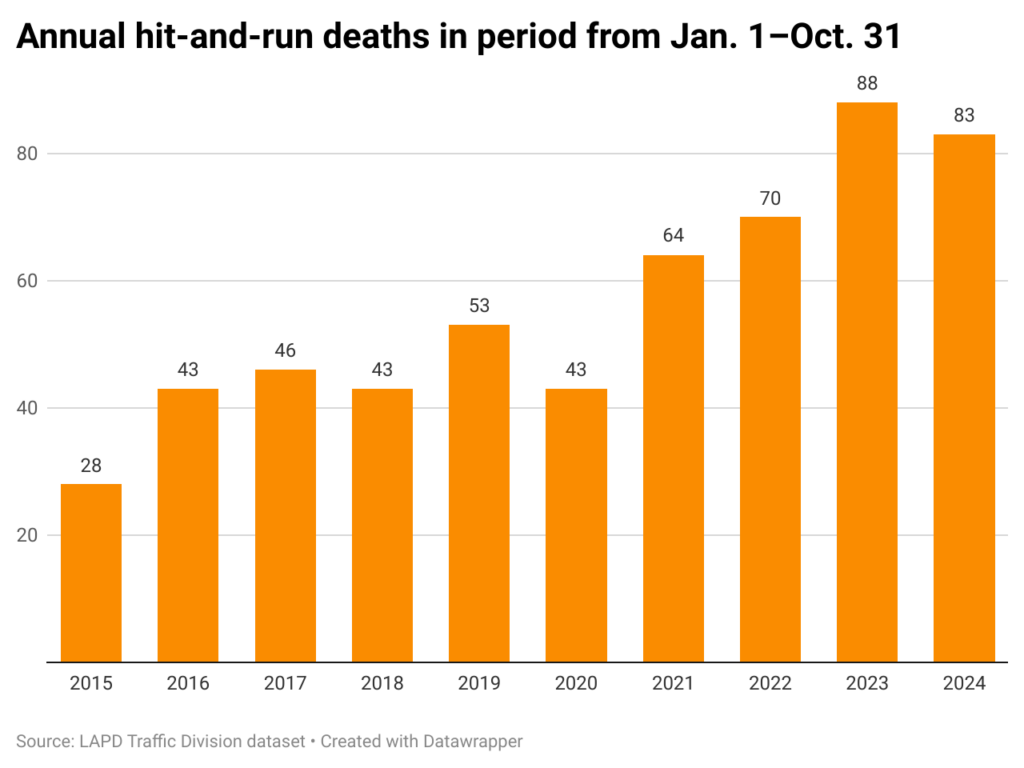

The year 2023 was disturbingly deadly on the roads of Los Angeles, with the 345 vehicular fatalities surpassing the number of homicides. That includes 108 people who were killed in hit-and-run collisions.

The situation remains nearly as troubling this year. Through Oct. 31, 83 people died in hit-and-run collisions, according to publicly available Los Angeles Police Department Traffic Division data. Although that is five fewer than at the same point last year, it is 18.6% above the number in that time frame in 2022.

From Jan. 1–Oct. 31, 2018, there were 43 hit-and-run fatalities in the city.

The worsening situation comes even as Los Angeles has taken numerous steps to try to make its streets safer. In March, voters approved Measure HLA, which is intended to enhance safety for pedestrians and cyclists by expanding bike and bus lanes on city streets. Back in 2015, then-Mayor Eric Garcetti launched Vision Zero, an initiative that aimed to eliminate traffic fatalities—by 2025—by re-engineering streets and other safety measures.

Instead, the number of hit-and-run deaths has been increasing, with almost uniform annual upticks over the past decade.

The LAPD did not make a representative available to discuss road safety despite multiple requests.

More dangerous vehicles

Los Angeles, like many cities across the country, saw vehicular fatalities rise after the onset of the pandemic. Although fewer cars were on the road, experts said people were driving faster than in the past, thereby increasing the damage suffered in a collision.

Even as traffic has returned to pre-COVID levels, road deaths are higher in Los Angeles than they were in the 2010s. The increase has been blamed on factors including more people driving large and heavy SUVs; people distracted by cell phones, whether drivers or pedestrians; and poor street architecture and dim lighting.

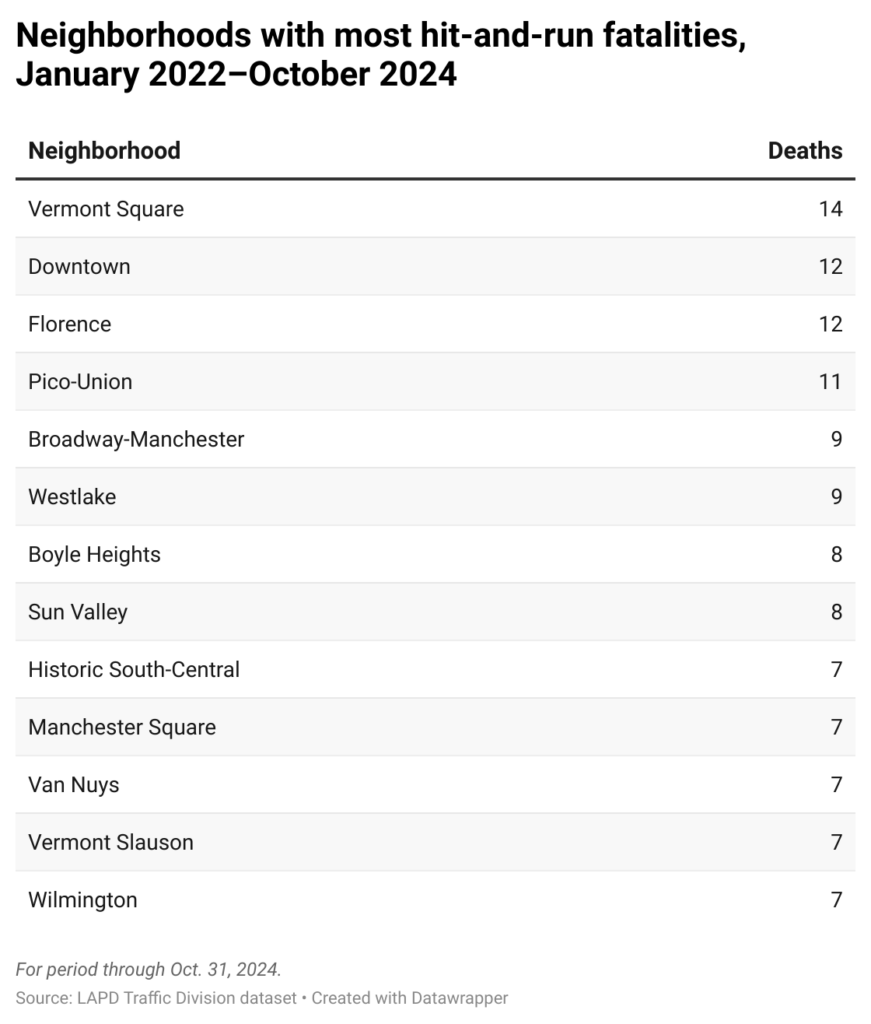

Hit-and-run deaths began increasing significantly in the city in 2022. From the start of that year through Oct. 31, 2024, the neighborhoods with the most fatalities are Vermont Square, with 14, followed by Downtown and Florence, with 12 each.

In recent years, portions of South Los Angeles have suffered outsized numbers of hit-and-run deaths. From Jan. 1, 2022–Oct. 31, 2024, there were 42 such fatalities in the area patrolled by the LAPD’s 77th Street division.

The next highest totals were in other parts of South L.A.: Southeast division, with 29 deaths, and Southwest, with 28 people killed.

By comparison, in that period there have been eight fatalities in the department’s Van Nuys division and seven in Northeast division. The lowest number of hit-and-deaths in that period is the two in the West L.A. division.

[Get crime, housing and other stats about where you live with the Crosstown Neighborhood Newsletter]

The fact that South L.A. communities see the most hit-and-run deaths is not a surprise, said Damian Kevitt, executive director of the advocacy group Streets Are For Everyone (SAFE). He said the area faces numerous shortfalls, including poor road design and insufficient traffic enforcement by police. That, he says, leads to excessive speeding and, consequently, more hit-and-runs.

Yet the situation extends beyond South L.A., Kevitt said. In January, SAFE published a report giving Los Angeles an “F” for its attempts to prevent “traffic violence” in the car-centric city.

“LAPD is not even responding to traffic collisions or reporting on them,” Kevitt asserted. “It’s not a priority for them.”

Kevitt, who is a victim of traffic violence himself—he lost a leg in a hit-and-run—said that the city has not done enough to curb the leading cause of fatalities and injuries on the roads: speeding. According to the SAFE report, in 2022, more than one-third of the city’s collisions resulted from vehicles traveling at unsafe speeds.

Since 2022, there have been 279 hit-and-run deaths in Los Angeles, according to Traffic Division data. Communities of color are disproportionately impacted.

Although people of Latino descent account for about 48% of the population, they make up 52.6% of those killed in hit-and-run collisions. Black people represent 22.9% of hit-and-run fatalities despite comprising just 8.6% of the city’s population.

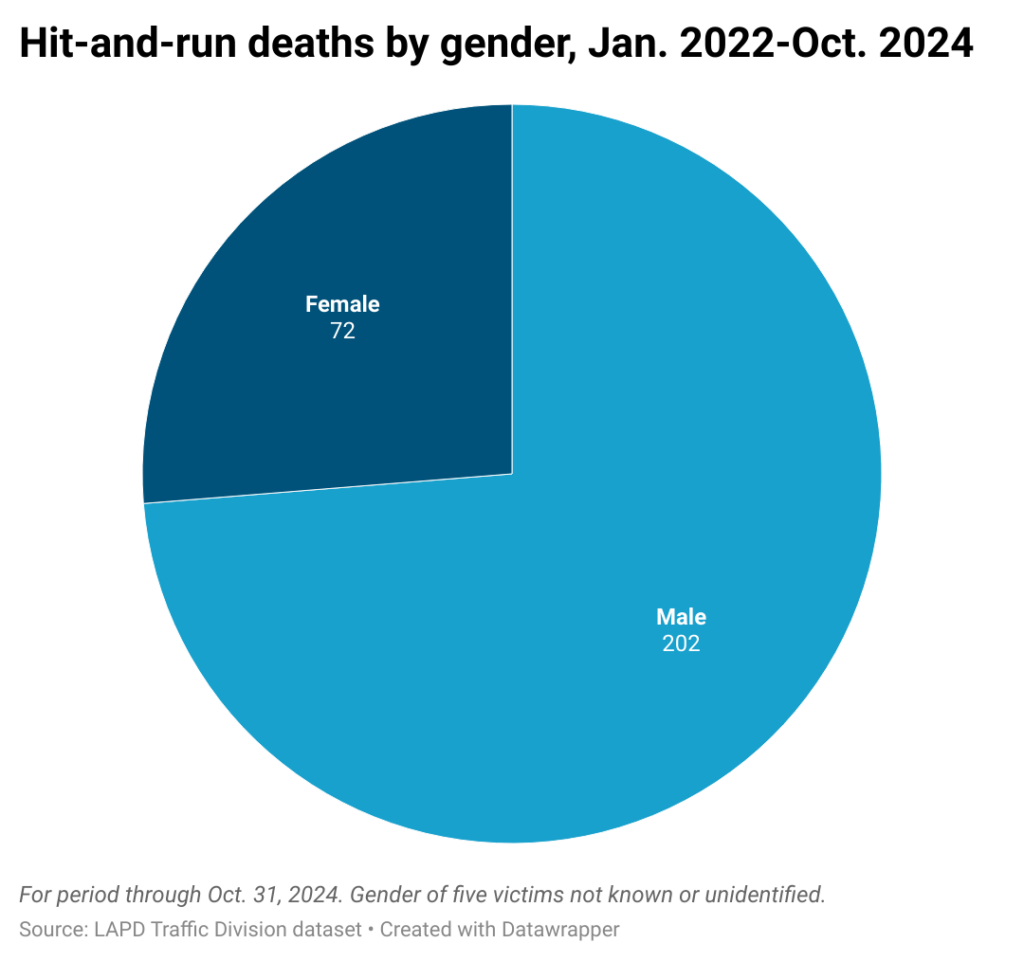

According to Traffic Division data, 72% of hit-and-run victims in the past three years were male.

Worse situation for cyclists

City law mandates that drivers who strike another vehicle, pedestrian or bicyclist must stop and render aid, and call 911. Many, however, speed away.

That was the case in August when comedian Perry Kurtz was killed in a hit-and-run in Tarzana. Kurtz was struck by an 18-year-old driver late at night in a crosswalk. The teen fled; Kurtz died at the scene. The teen was later identified and arrested.

Also increasingly at risk are bicyclists. According to LAPD data, nine cyclists have died in hit-and-runs so far this year; the recent annual high for bicycle hit-and-run deaths was nine in 2019 and again in 2023.

Altogether this year, 21 bicyclists have been killed in collisions, according to Traffic Division Compstat data. Another 130 people suffered serious injuries.

Michael Schneider, founder and director of transportation-focused advocacy group Streets For All, said bicyclists are “being pushed to the margins” of the roads. With streets in the city being designed like freeways, with wide lanes and synchronized traffic lights, the result, he said, is more speeding, which endangers cyclists and pedestrians.

“L.A.’s streets try to move a lot of vehicles while also allowing for pedestrian crossing and cyclists,” Schneider said. “It’s trying to be everything to everyone, and instead it kind of sucks for everybody.”

Hit-and-runs involving two vehicles account for only 8% of deaths this year. That rises to 10%, or nine fatalities, when including motorcycles.

How we did it: We examined publicly available collision data from the Los Angeles Police Department Traffic Division from January 1, 2010–Oct. 31, 2024, as well as LAPD Traffic Division Compstat data. LAPD data only reflects collisions that are reported to the department, not how many collisions actually occurred. In making our calculations, we rely on the data the LAPD makes publicly available. LAPD may update past collision reports with new information, or recategorize past reports. Those revised reports do not always automatically become part of the public database.

Have questions about our data or want to know more? Write to us at askus@xtown.la.