[dropcap size=big]I[/dropcap]n elementary school on the border our Cinco de Mayo festival was the biggest day of the year. Each grade, kindergarten to sixth, presented a musical dance number in full costumes, usually ballet folklórico or zapateadas, on a stage set up on the school’s playground. We had a tradition of selling egg shells filled with paper confetti. For one day a year, this would turn our vast playing field into a sea of wind-whipped bits of colored paper far into the evening, after the kids spent hours running around to smash the eggs on each other’s heads.

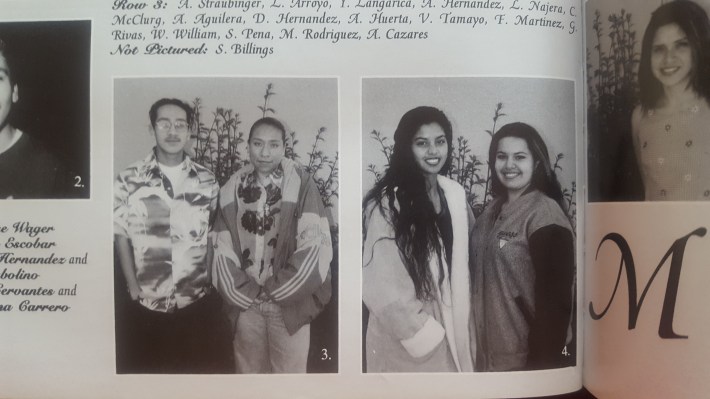

In high school it was the same thing, Cinco de Mayo was a big deal. Our campus chapter of MEChA organized an assembly and the entire school attended: we presented folklórico dance numbers, poems, Aztec-inspired dancing, and political speeches. We raised funds for the club by selling Mexican food plates.

As Cinco de Mayo approaches in 2019, these kinds of memories no longer seem as banal and normal to me as they once did. For a long time I had never met anyone who didn’t have a lavish Cinco de Mayo event at their school. It was just what you did. But today, with white supremacists setting policy inside the White House, remembering and embracing these mexicanish traditions seems like an almost radical proposition.

Fact is, generations of people in communities with large numbers of Mexican descendents — that means anyone, that means you — know that Cinco de Mayo is a cornerstone of public/social life in American-Mexican identity. When you subtract the corporatism, the consumerism, the stereotypes, and the alcohol, this gringo holiday is one of the building blocks of who we are, for better or worse.

Tacos, as we believe at L.A. Taco, are the only banner that can unite all residents of the USA.

[dropcap size=big]T[/dropcap]he north-of-the-border roots of Cinco de Mayo go way back, like to the days of Lincoln, when people on the West Coast and in the broader Southwest were just as invested in the Civil War as anywhere else. The Battle of Puebla in 1862, in which an outnumbered band of Mexicanos fought back and defeated the invading French army (momentarily, but still), must have been a big story in the north.

“Americans of Mexican descent used [Cinco de Mayo] as inspiration for the Union struggle,” the History Channel notes. “Americans in the midst of Civil War were inspired by the Mexican victory and began celebrating the Fifth of May with parades, dances, speeches, banquets, and bullfights.”

Somewhere along the way, the beer companies must have noticed.

In the past forty years or so, “Cinco de Mayo” gradually transformed into an all-out slugfest for who can get the drunkest and make the most money off of it. There will be Cinco de Mayo drink specials at basically any bar in America on Sunday. People slap on sombreros and fake mustaches and behave like buffoons under the silent premise that Mexicans are stereotypically shitfaced drunks — and therefore Cinco de Mayo is about drinking.

We’ve spent the last decade raising our voices to screeching heights over the misuses of Cinco de Mayo by American marketers and corporations, and against the stereotypical characterizations that accompany it. It has not worked. Cinco de Mayo, like Saint Patty’s Day, has entrenched itself in American life as a crude form of cross-cultural celebration on a massive scale.

RELATED: What President Lopez Obrador Means for Los Angeles and Mexican-Americans at Large

But if you take a look, as I did recently, to postings about Cinco de Mayo events in cities across the country, the holiday does allow for more substantive learning and sharing on Mexico and Mexican Americans, at a time when definitely we need it.

I literally just did this, went online and searched “Cinco de Mayo” and several random cities in the South and Midwest: dozens of gatherings planned on Saturday and Sunday at galleries, cultural centers, parks, and yes, bars and restaurants. Like this event at Guadalupe Centers in Kansas City, or this “Festivale Cinco de Mayo” at the Historic Valley Junction in Des Moines. (Whoops, KC, I also found a "naughty" Cinco de Mayo party for straight swingers, go 'head!)

These kinds of events, however lame, allow non-Mexicans to sort of tiptoe around the broader culture and find some point of contact: usually that’s food and drinking, which many Americans already associate with the most basic kind of Cancun or Cabo vacation. Tacos, as we believe here at L.A. Taco, are the only banner that can unite all residents of the United States of America. Even the super racist ones, as Donald Trump demonstrated with his taco bowl on the historic date of May 5, 2017.

So here’s my proposal. Let us accept Cinco de Mayo for what it is, but also reclaim and update its meaning for what it could mean for us today. Think of it as a holiday to Mexican resilience. And since our cultures are always shifting and transforming, consider Cinco de Mayo an open template, suitable for molding to today's needs.

So many people seem hate us simply for existing, let’s be honest. Mexicans in the most vile lens are seen as loud, uncouth, braggadocious, they’re untrustworthy, they take up space, they’re dark — the hostile corners of American society hold these beliefs and surely worse of us or anything “Mexican,” which unfortunately tends to include Central Americans and South Americans when they are lumped in with us. (That’s not the Mexicans’ fault, but I can see how it can be frustrating.)

William Nericcio, a professor of English at San Diego State University and author of “Tex[t]-Mex,” said he’s also feeling a sense of resignation over the inevitable “Cinco de Drink-o” displays expected from coast to coast this weekend. But he’s cool with it.

“It’s the epitome of an American construct,” Nericcio told me. “In the age of the rise of the renaissance of anti-Mexican hate, I think, ‘Hey, good thing.’ Anything that gives the general population an excuse to associate Mexicans with happiness, it’s got to be a good thing.”

RELATED: Ultra Popular Tacos y Birria La Unica to Open Second Taco Truck: Exclusive