LOS ANGELES - Here, in what is currently Los Angeles County and the historic land of the Tongva people, is a wounded history full of energy to be released, which makes this land the perfect place for desmadre, which is to say, the perfect place for putazos, that are consented of course.

“My Mom was a heavy metal Chicana,” Kristy Martinez, a Ph.D. student at UCLA studying Musicology, tells L.A. TACO.

While October 15th marks the end of the U.S federal Latinx Hispanic Heritage Month, L.A. TACO is setting a commitment to honor heritage during the full year. So much of what has been uplifted during the month still misses the question around what has been inherited and who does the giving and offering into the future.

I’m endlessly curious about what we inherit, whether through family or the chosen kin, depending on where you are born, where you move, and where you decide to call home as you grow older. In some research this month for this piece, I realized that we’ve inherited a love for desmadre that is unique to Los Angeles.

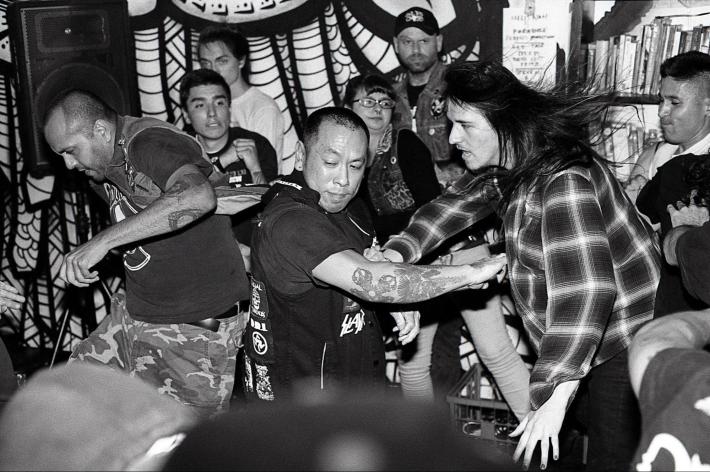

Cities like Chicago, San Antonio, Oakland, Boston, and New York City have their own bands, scenes, and traditions—but have you ever walked through a small living room in South Central where a señora is making quesadillas and you walk outside to see a band raging on about colonialism with ponkas, mod heads, a Chicano studies Ph.D. student, Black punks and foos throwing each other around?

“I had a gig last night, sorry,” Kristy apologizes for a sore voice in a kind but not so sore voice. The lead singer in Observer Syndrome, Kristy navigates late-night seminars, writing, parenting her son, band practice, and performances. Her first show was in Temple City, then heading out to Compton and southeast Los Angeles and the San Gabriel Valley for more shows.

She tells me about how more and more Indigenous musicologists and writers are finally getting recognition for describing how moshing is a form of ceremony and a place for healing, echoing the incredible documentary from REVOLVER on what heavy metal means to people in the Navajo reservation.

Everyone I talked to for this essay was asked a similar set of questions: What was your first show, why did you keep going to them, and does this scene and subculture fit in what we call “Latinx Heritage?”

Growing up, the first show I attended was in my own backyard at a house my parents shared with three other families in Anaheim. My cousin, Stephanie, in the early 2000s, had a Quinceñera that was out of town, so the whole family decided to stay away for that weekend. My cousin Ale, however, decided that this was the time to throw a show. As we unexpectedly decided to come back home, there was a wave of people jetting to their cars and a roar in the backyard, a roar that called me. My prima had Tijuana No playing in our backyard, and the beginning of my journey in this desmadre had begun.

Someone I’ve seen at shows in recent years has been Moni Aguilera, aka Moneycaa on Twitter, whose tweets on Latinx culture have made me chuckle on multiple occasions. Recently, Moni tweeted, “I’m such a thot for anything L.A., I’m sorry,” and though I immigrated here and left to Orange County and came back, I feel nothing less more relatable.

One thing I truly wish I could relate to was how Mony’s first show was at school when Cafe Con Tequila came to play at her high school during lunch. Born and raised in Koreatown, shows in Downtown and South Central were the most accessible to see bands like The Red Pears, Jurassic Shark, Viernes Trece, and Redstore Bums.

“I mean, I was angry, OK?” Moni laughs when she says and slows down to remind me,

“- I’m the eldest daughter in a Mexican home,... while there weren’t a lot of women in bands, these are one of the few spaces where you can be angry.

I’m allowed to be angry here. I’m allowed to be wild,

[the anger is] validated, and seen-

there were other people that were angry like me.”

Mandie Torres, aka DandyMandie, has anchored on my arm during some shows in recent years. A rockabilly for life, Mandie has graced the pits of Catch One, Los Globos, and numerous backyard shows in South Central. While she has taken a leave off of social media after acquiring almost 100,000 followers, she wrote to me about what being in a pit also gave her:

“I love the way you can throw putazos one minute, then it breaks down to a reggae-rocksteady beat, and throw in some cumbia. They’re just so much fun, and I made so many friends through shows. They were an escape from the struggles and stresses of life. I remember I used to literally go every Friday and Saturday, and if there were any Thursday and Sunday, I would be there too. But then you know life happens, you grow up, have more responsibility and other shit to take care of, so I no longer go as often, but shows will forever have my heart. You’ll probably catch me when I’m older, taking my future kids to shows, lol.”

For Miranda Ynez, this music and the scene were a way for her at first to build community and also grow closer with her family. Before the ska shows in community college and eventually forming a band with her siblings, Miranda, like many forced Catholic Latinxs, sang in an all-girl choir and grew up with music all around her.

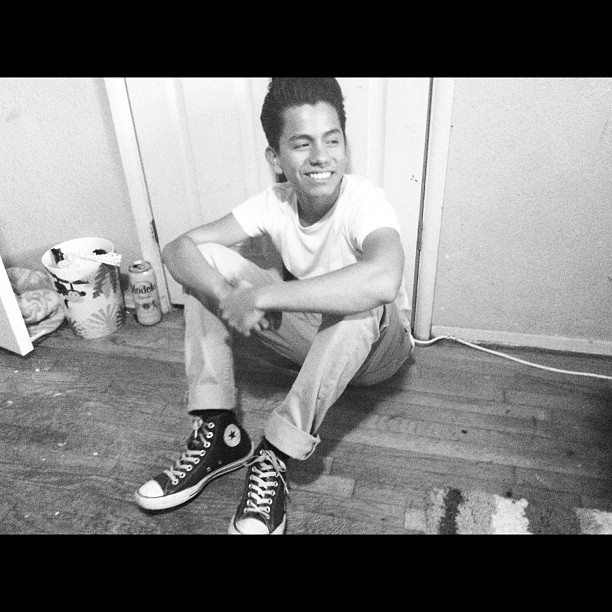

“I’ve broken my ankle stage diving,” Miranda Ynez, born and raised in East L.A. I met Miranda in Texas in 2019. She is a visual artist, art manager, and educator who has cultivated work with multiple organizations, but before we met at the NALAC Leadership Institute, she was part of a band called RIVOAH and was so deep in the scene that she got carried onto her Rio Hondo College graduation in a golf cart.

As we looked through her archives together, Miranda would blush and hide but then beam with joy when she recalled what the band meant to her and her siblings. “We played everywhere eventually and even played at the HAMMER and Getty museums.”

The names of venues are endless from The Cobalt Cafe, Get Involved, Anti-Club, The Smell, UnFair Oaks (in Pasadena), The Living Room in Goleta, and The Watts Cave. I also can’t talk about memory and archives without talking to Dr. Jorge Leal, UCR Professor of History and the founder of Rock Archivo de L.A.

He reminded me of Reynaldo Rivera’s quote: “L.A. is thick history but a short memory,” noting that so much of what this scene, the venues, and the music carries on 35 to 60-year history depending on where you start and what you want to categorize but also arguing that so much has already been written, but there is still so much to document.

We talked about territorial preservation, the importance of mapping out the venues, but we truly narrowed down the reality that this music and its scenes are part of the legacy that is part of those long histories of radicalizing and theorizing about our existence in this diaspora, even if we haven’t gone to college.

So many bands like La Banda Eskalavera, Generacion Suicida, Viernes Trece, Rasakahuele, Los Ilegales, and Sepultura bring out Latinx crowds across the city to sing and yell along to songs about injustice and resistance. This tradition has graced many backyards and venues that have long disappeared but remain in memory and the stories we tell.

Before the Sofi Stadium, there was a place called Hollywood Park, a horse racing venue where Chris Estrada attended his first show ever to see the one and only Gloria Trevi. A Rocker-Foo-Stand Up Comic who just had a show ordered at Hulu, Chris grew up with friends in bands in Lennox and Compton.

He tells me that the Los Crudos split record with Spit Boy was the first time he heard punk in Spanish, and it changed his life. In almost minute detail, Chris takes me through his journey in scouring the BREAKMYFACE.com website when it had a dot net domain during the dial-up days and re-reading Martin Crudo’s interview in the MAXIMUM ROCKNROLL magazine.

For Byron Scott Adams, a Black Salvadorean Artist, the scene was more than just the music. After attending one of his first shows at Chain Reaction, Byron began to frequent The Smell, where he got to meet other anarchists and punks who also loved anarchist literature and believed the scene was a place for community.

The Ponka Producer and Journalist Stephanie Mendez had to stop my interview with her to get someone on the record for a meaningful story a few weeks ago. Once we got back on the call, I learned that the first show she ever went to, like a true Santanera, was to see No Doub. She later grew to the ever-growing scene in Santa Ana, eventually hitting up more shows in L.A. as she grew older.

I’d be remiss if I didn’t plug her 2019 piece in the L.A. TACO trompo that is arguably a seminal guide to the scene with one of my favorite bands, TRAP GIRL making the list. And her tracklist of punk songs that describe Los Angeles in all its desmadre being an essential list you need to listen to as soon as you finish reading this.

The music critic and recent MacArthur fellow, Hanif Abdurraqib, points to musicians being tour guides to communities and places in his work. All the people I talked to pointed to a friend, a family member, or a lover as the person who brought them into their first pit or gave them their first cassette of a band their Mom hated. So much of what makes up this complex act of throwing ourselves at one another, picking each other up, and maybe hitting up a taquero afterward is what makes living in our constantly gentrifying but beautiful toxic air of a wasteland we currently call Los Angeles.

The shows that have made up the legacy of desmadre around us, according to everyone I talked to, points to how punk bands, hardcore bands, thrash metal bands, ska bands, and the overall sounds of grief, sadness, and anger bring us to understand what makes up the honest Los Angeles we hold on to, a city and county that you learn to love through the punches.