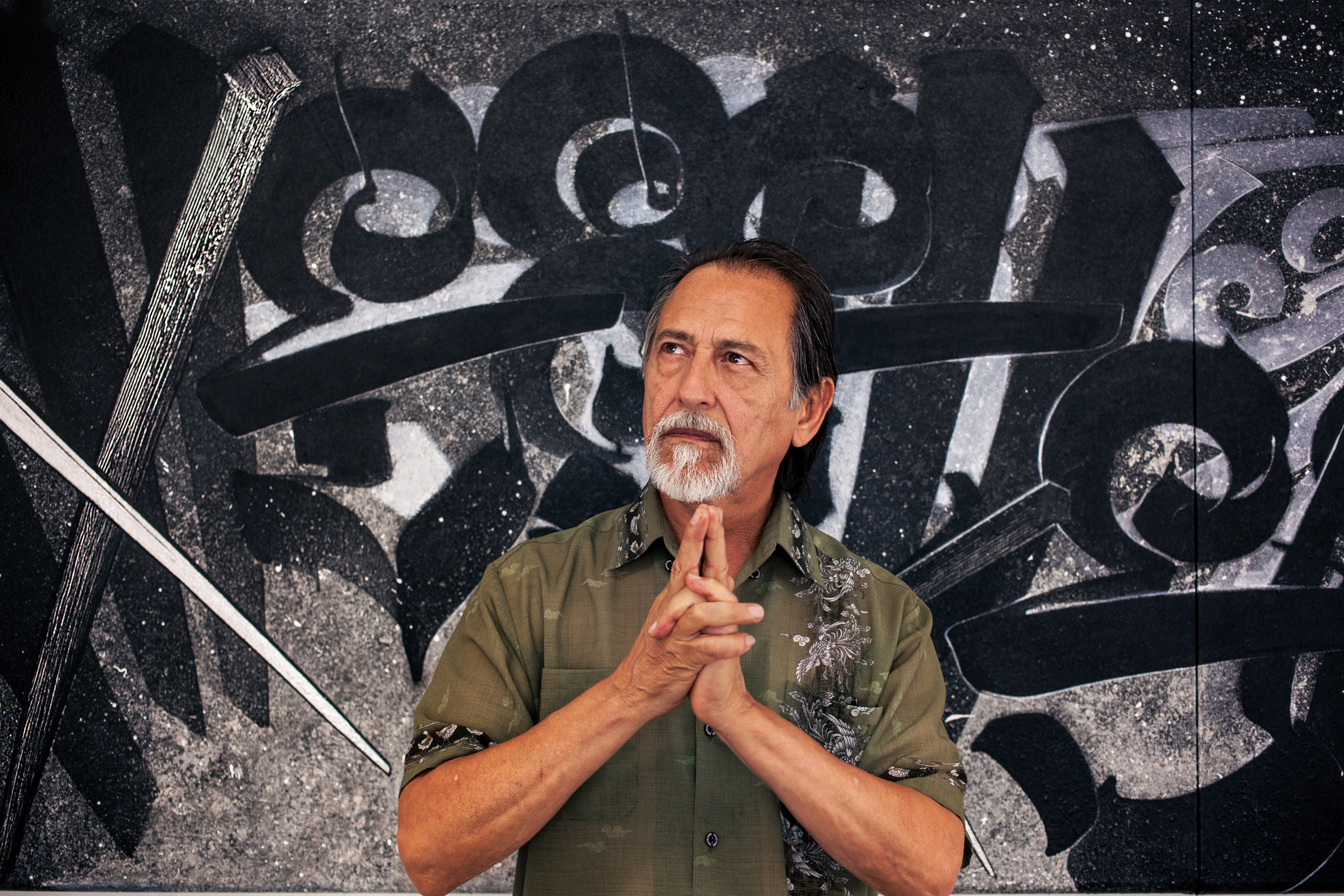

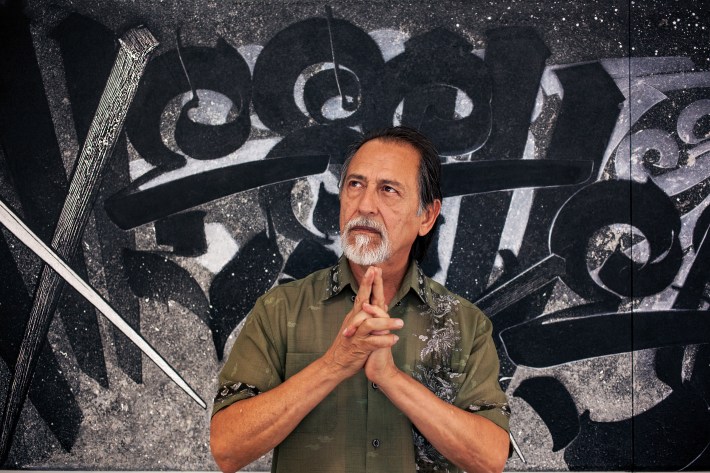

Photographer Castro Frank recently got the chance to photograph and interview one of his inspirations, legendary artist Chaz Bojorquez. Chaz has been one of the guiding lights in the LA scene for a long time, not just for his incredible art, but for his commitment to the community and his dedication to passing his knowledge on to the next generation. Castro Frank. asked him about his life, how he got his start, and much more...

Castro Frank: How does your work fit into what’s going on now?

Chaz Bojorquez: It ain’t my world any more. My world was the civil rights movement, the hippie movement, the feminist movement, the graffiti movement… but now it’s your world. At the same time, there’s a new movement of the youth that’s going crazy over the stuff we did in the 60s. Teen Angel Magazine, they re-released it, that was something from my generation. They stopped publishing but now they’re re-releasing it.

My stepson, Dominic, and his girlfriend Noelle who owns Mi Vida… I first walked in there and said “Damn, it’s all cholo wear!” She said no, this isn’t cholo wear! She’s educated in fashion, she went to FIT, she says, this is “urban wear.” I said, no it’s cholo! For her, you see, the cholo experience, she wasn’t born with that. It meant something for us at the time, for her it’s vintage. She was saying the golden age was the 80s… I said, really? I thought the golden age was the ‘60s!

But I’ve got to get on board, just to make sure my voice is still coherent and has meaning. Because the audience has changed. The audience is not about Cesar Chavez, school walkouts, that’s history. That’s over. That doesn’t mean anything to you guys— and it shouldn’t. They’re good stories, what we had to struggle through, but they’re not your struggles.

The other day I was with OG Slick, who I did a mural with in Hollywood, and some cholos came up to me, they were from Highland Park. We started talking about different old-school places in Hollywood, like Pandora’s Box and I said, “yeah I was there once with Sonny and Cher,” and they said, who’s that? (laughs), I get a lot of that!

My generation is over. But I meet a lot of people who’ve been influenced by what I do, and they’re interpreting it in their own ways.

CF: A lot of people are bringing back your era, in fashion and music… but something is missing.

CB: The gangsters. The hard part. The villains. The drugs. Someone told me, we like the cholo stuff but without the violence, we like the fashion but we don’t relate to the hard stuff. People look hard, with the tattoos and everything, but they’re not.

CF: It became a fashion thing. It’s become more of a trend.

CB: In my day, we would never wear a t-shirt with a letter or a brand name. That was taboo. You had to be clean clean clean. No commercialism. My uncle in the 1940’s, he was a zootsuiter, he said you couldn’t buy a Zoot Suit. You couldn’t just go buy it—you had to have it custom made from a tailor, and they were $200 in the 40’s. That’s a lot of money when you’re making $35 a week. They used to call them drapes.

This identity, this old-school cholo thing that’s come back again, it’s different in some ways, and it’s a whole lot bigger now than it was in the 50’s and 60’s. All that style is back. So, damn, well, it helps my career! (laughs)

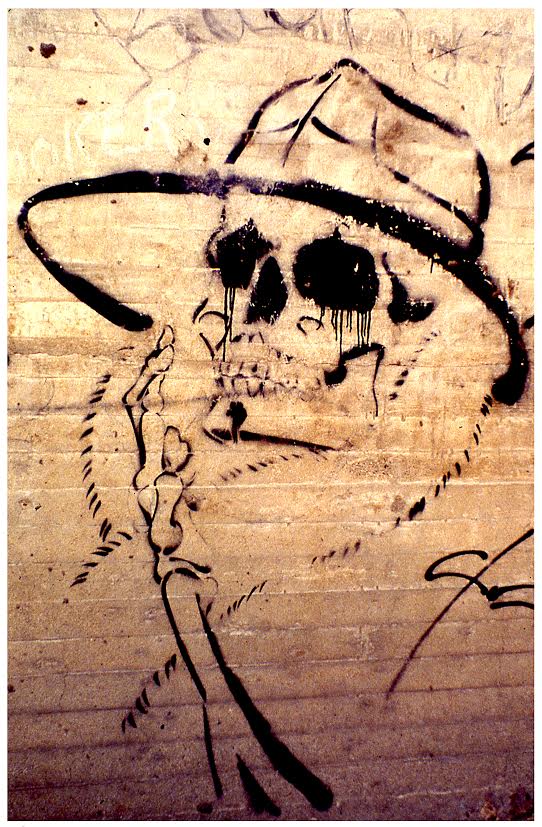

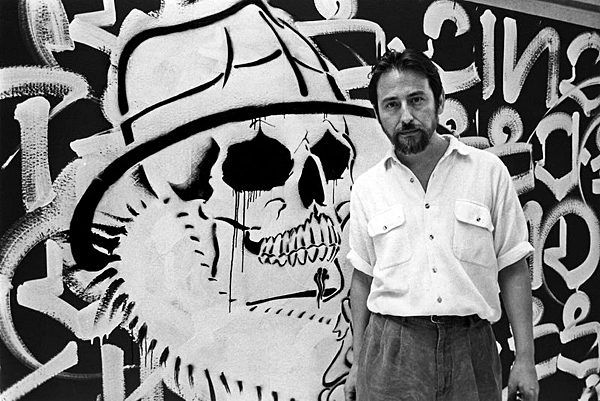

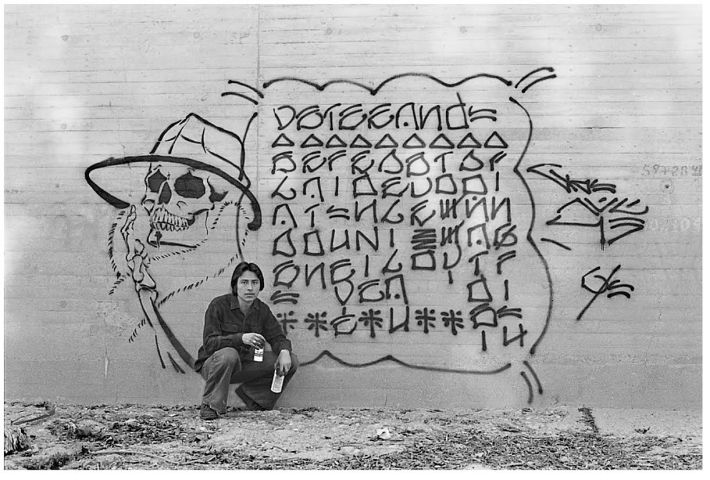

I did Senor Suerte in ‘69, trying to find my identity. I was 19, so I started graffiti a little late. I couldn’t see any of my own identity in the New York graffiti. All the balloon letters and all that stuff, it wasn’t happening for me. I wasn’t a gangster, but I lived in a gangster neighborhood. At the same time, the hippie movement came in, so I was a badass hippie. I went through the doors of perception many times. But I always knew what I wanted to do was art, so I started doing my paintings, and my first graffiti style artwork.

But at that time, they didn’t understand calligraphy as artwork, they didn’t understand cholo culture.

I first went to art school at Chouinard, they moved to Valencia, and became Cal Arts, and I had to resubmit my second year-- I was a ceramics major. I had to reapply and they said I wasn’t good enough, so I was kicked out of art school. I wasn’t good enough. Since then, I’ve given lectures there, also at Otis, Art Center, The Smithsonian and The Kennedy Center. Plus around the world. But at that time, they didn’t understand calligraphy as artwork, they didn’t understand cholo culture. Since Baldessari was there, it was all about assemblage and conceptual art. That was the new thing. Baldessari said that painting was dead at that time.

CF: How did that make you feel? Were you discouraged?

CB: It made me self-reliant. They didn’t like it anyway, so fuck ‘em. I would go to museums, I never saw any Latinos on the walls. At Chouinard, very few Latinos. And they were mostly privileged kids from Mexico City with chauffeurs.

CF: Have you seen times change? Are more Latinos involved now?

CB: Oh yeah. We’re everywhere now. Everywhere. What has changed is the communication, the iPhone. When we were going around and wanted to have a meeting, you had to walk around with a pocket full of dimes, so you could stop at liquor stores to make a phone call, to let people know what was going on. We’d have meetings with 7 or 8 people, and thought that was a lot! We had to write letters and wait back and forth! And that wasn’t that long ago…

Our Chicano movement was basically one to one. It was slow, it was deep, it was just us. Now my voice gets out there instantly, and the Chicano movement is all over the world. Luis Rodriguez, the poet, he wrote this one story called “There is a cholo in Milan” which is about this guy, he’s a friend of mine, called Fly Cat. He does graffiti, all gangster block letters in Milan. He hated to be Italian, he said I was born to be a cholo.

Who have we become? We’re regionally based here in SoCal, but we’re internationally known. Our influence is now not just the city of LA, it’s the world. I was in Melbourne Australia once, some guy taps me on the shoulder… I can tell he’s a tattoo guy, tattoos guys have a certain look… he shows me he’s got my letters on his body. He showed up just to see me and show some respect. And I get that in Spain, New Zealand, everywhere I go.

CF: When you started, graffiti wasn’t respected as an art form. How did you succeed in spite of that?

CB: Being thick-headed and angry. Because who rejected me first were the Latinos. It took ten years from me working in the streets until I did my first painting. I did my first painting in 1980. I had just come back from travelling around the world for a year and a half. I realized that I saw all these languages, ancient ruins with letters and statements and carvings in walls, I saw all the history of humanity in letter form. I came back with knowledge, and I did my first painting then. I did a roll call painting.

After a couple years I started showing these paintings in a couple of places in East LA like Self Help Graphics… they all hated it. Sister Karen, bless her heart, I love that woman, but she said “This is gutter art. This is anti-Chicano. We’re trying to push the Chicano identity, and this gangster art, this bad boy art is undermining everything we do.” Because Chicano to them was Cesar Chavez, family, religion, suppression, migration, all that. They said this ain’t Chicano art!

I said, OK they don’t get it. I was confident that I knew enough about art… I was still young, but I was stubborn enough to say this is fine art, this is about identity, this is a social statement, this is about who we are. In some ways I hated conceptual art, but it was conceptual.

CF: So you always knew this was fine art?

CB: When I saw graffiti I fell in love with the cholo, the writing, and the spirit, the capital letters, it was about OUR neighborhood, nobody else. Since my grandparents were from Tijuana, and my father had been born there, we’d always go back. And there I would see all that funny, kitsch border art. Not Mexican, not American, but border art. Porky Pig piggy banks, Blue Elvis, black velvet paintings, that kind of stuff. And it was art to me.

Then, when I was seventeen, my mother got me some sculpture classes in Pasadena, at the museum of art. She always supported me. The big show at that time was Marcel Duchamp. When I saw his nude descending a staircase, his bicycle tire on a stool, his urinal… I thought, if this artist who’s famous, can call this art… then graffiti is art...

And then I met him. I sat down with Marcel Duchamp in the patio, and he asked me what I do, and I said I was trying to be an artist. He said, you don’t try. You are. You just make art.

What I’ve learned from graffiti, is that you don’t need permission. Graffiti taught me how to be a badass. Don’t listen to anyone else. I give a lot of lectures about this, and I have answers for every stupid question they ask me. Is graffiti art? Aren’t graffiti artists just like dogs pissing on a fire hydrant? Am I responsible for putting youth into prison for graffiti? I say, let’s get to the point-- this is art, and this is us. But it took me 45 years to get people to dig it! Only recently have people gotten my stuff! Some artists, insiders, they always supported me but they were just a small group.

CF: Is graffiti a political act?

CB: Sure. Yes. Because you do it in a public space. For one, my day job was advertising for movies. I would do layouts for movies and for newspapers, magazines, one sheets. Billboards, brochures, everything… I would do all these movie ads and realized how ads were made and placed into the public space. So who owns the public space? Because right next to graffiti would be a billboard selling cigarettes. So who owns it? Just those who can afford to buy it? So when I started to see graffiti going up on billboards, I said hell yeah.

What I’ve learned from graffiti, is that you don’t need permission.

The youth may say it’s not political. They might say, man it’s just vandalism! The older people are the ones saying, no it is a political statement. You’re expressing who you are, your community, and what’s important to you, what makes you proud, and what you don’t like. In the 90’s we had vigilante killings and many issues with the youth, and we were still trying to still find that Chicano identity. All the graffiti guys in the early 90’s were copying New York-- I would tell them, man don’t do wildstyle. They’d say we don’t want to do Cholo style because we hate our older brothers, they’re all in prison. I would say, then find your own voice.

Graffiti is a political act. We have a message. You know, all my graffiti has quotes. And later I learned that my graffiti has advertising aspects to it. I learned that actually a lot of my graffiti has movie aspects to it also. Let me describe what I do… there is a lot of Hollywood influence. For one, Disney. They had the best color in all of their films. I think it influenced all the Chicanos growing up. I would meet phase2 and these fools from New York and they would say, we don’t do graffiti in LA because we have too many characters, and we don’t have any subways. And I said, yeah it’s all true, that’s what makes us different, and better! (laughs).

So in my graffiti, it's like a storyboard… I had a character, evident or not. I had a voice, a dialog, had a story with a conclusion. I also had a venue, a place, a setting-- this is the streets of Highland Park, this one is in the streets of the barrio. I had lighting, it could be street lights from above, sunlight from the sides, or it could be stage lighting from below. My paintings are a storyboard also. I put quotes, because there is dialog. My paintings aren’t just an image, they’re talking. You’re supposed to listen to them. You look at my work with your ears also. But that’s us-- I’m talking about our words, roll call, identity, region, time, and our pride.

CF: I can see in your work that lighting is important, you can see the various angles of lights from different directions…

CB: I even had a series of paintings that were shadows. Because in the LA riverbed, the bridges above cast giant shadows onto the concrete walls, very beautiful. It showed maturity, a sense of time, and sense of place.

CF: I see these dots in your paintings, four dots, what does that mean to you?

CB: You can see in some graffiti, three dots, which represents ‘mi vida loca’, or could mean the father, son and the holy spirit. In my work the four dots stand for luminosity, it’s the spirit light that will put light in front of your path. Or, watch your back.

If I had to have a religion it would be Buddhism. Because what I learned by Buddhism from travelling around the world and projects I’ve done with Buddhists, is that they accept everybody and everything, with moderation. You can live your life in harmony and be a good person… a little bad, a little good, karma balances it out. You don’t need an outside force, or magic to define who you are.

I always advise people-- don’t listen to what people say. People will say anything at anytime, it can be the truth or not, it’s just the moment. Watch what someone does, then you will know what kind of person they are. I know people who give a lot of money and talk about helping, but they’re jerks. And I know a lot of nice people who don’t help others.

CF: I've spoken with my wife about trying to find a place where we can just live our lives, without judgement.

CB: If you’re out there doing bad things, bad things will come back to you. And the reverse is true too-- if you’re out there doing good things, it will come back to you too. Count on that. It’s hard for people to understand that if you’re a good person and you put yourself out there, good things will come back to you. That’s what I did with my graffiti. I kept my graffiti positive, I moved forward, and I kept focus on constantly doing my graffiti, having a voice in the world. I could’ve given up a long time ago, because I wasn’t making any money off graffiti, but I didn't give up.

CF: When did you first start making money and realize you really had something going with your art?

CB: Well, that’s two questions. After I came back from my travels, I had my job doing movie ads, which gave me money. I was able to buy a house when I was 31 years old. I always had a job, I always had money. When I was 35 and I told myself I need to give up this day job. I’m driving a Jaguar car, I’ve got money, my wife is bringing in money as a waitress, we went on two vacations a year, but I wanted to be that artist that I always was, that I always wanted to be.

So I quit my day job at age 35… I got rid of the Jaguar. My wife hated it. I think I brought in $350 the first year, and our money just went down, and down. But I was happy, I started a whole new series of black and white paintings. I slowly started selling. $1,000 a painting maybe.

It wasn’t until I was 60 years old that I started to make real money from my art. I also did things around that time with brands-- Converse Chaz shoe, Vans Chaz shoe. Nike Black Mamba Kobe XL clothing line, Tribal clothing. Commissioned murals, and paintings that sold globally.

There’s two people involved in the business side of art. There’s our side, the artist’s side, our discovery, our vision, our journey. And there’s the audience. They need substance. They need the back story, the why. When I first started showing my graffiti art in East L.A., they didn’t ask me “what”, they asked me “why.” Why are you doing this? Why graffiti? They didn’t get it for the longest time.

I had the Long Beach Museum director show up at an open studio that I had about 20 years ago. He got so upset and angry, he yelled at me! He said, I would never put this in a museum! That same painting that upset him later on ended up in the Smithsonian, in the permanent collection.

CF: How did you respond to that level of anger towards your work?

CB: I just said, well he doesn’t get it. It really bothered my wife though. She felt that I was going the wrong way. I wasn’t making money, my work had no value. So then John Valdez gives me a call one day, and he says “hey man we’re in a big Chicano show, down in El Paso, and I talked to the curator, he said they’re having trouble insuring the art because Chicano art isn’t worth anything!” I said, oh wow I guess they have a point, we still have no value. They don’t get it. We don’t fit in American art history. We don’t have a place. So we got on the case of Senators and Councilmen and forced them to address the lack of Chicano identity in national museums. It was a big political thing, and they forced the curators to start collecting some of our art in the early 90s. When they came to me, even some of the Chicano guys said “why Chaz?! Why graffiti?”

One powerful image can make your career.

I was in a big show in San Diego of Cheech’s art, and the curator said she didn’t know why I was in the show. She didn’t think I was part of that Chicano movement. I said, this is our words, and our own voice. Latinos and curators gave me the hardest time.

Finally I went to gallery in Hollywood. Zero One Gallery. Rock ‘n’ Roll. Met Big Daddy Roth, Robert Williams, and they went wow Chaz, this is gangster art, that’s cool. They embraced me. Because people didn’t respect graffiti as art, and people didn’t respect cartoons as art. Those guys wanted to self-validate like the Chicanos did, like graffiti did… so Thrasher Magazine had some extra paper and out of that came Juxtapoz Magazine, which is now the second biggest art magazine in the world.

CF: I remember when I was young, seeing the spiral staircase off the 110 by the 5. I looked for it every time I drove by, before I even knew who it was.

CB: One image can make your entire career. So many people have told me that story, just as you told it. As little kids they were scared, they were in the valley of the skulls, which I had tagged from Pasadena to Highland Park. That was my territory. We didn’t go All City. We didn’t tag LA, we tagged our neighborhood. That was my first tag in 1969. I was so scared. They used to call me Charlie Chingaso (laughs), that still cracks me up.

My real name is Charles. In art school they started calling me Chas, I didn’t know what Chas meant. I never knew it was an abbreviation of Charles! Latinos don’t say Chaz. I changed the "s" to a "z" to match Bojorquez, though. I was also known as Charlie Chingaso, a name my friends gave to me… we were hippies, taking acid and smoking dope and thought it was funny because I would always fuck things up. My cars would catch on fire, oil dripping everywhere. I remember one time, my car was all messed up and there was a little weed plant growing in the back on the floor because the rugs were all rotten, and a little plant grew up out of the floor! I had a chinese lantern hanging in my ‘51 Chevy coupé. Messy, grisly, hippy… Charlie Chingaso.

So when I did the skull, my first tag in 1969, I was so nervous I misspelled Chingaso on the spiral staircase. It was on the bottom, you could see it, but it was spelled wrong. It got covered up in ‘84 for the Olympics. The city covered up all my tags, some of them ran from 1969 all the way until 1984.

CF: Do you have pictures?

CB: Yeah, but we didn’t have any money for a good camera, I had one of those little cameras, I don’t remember the name, it made slides that were half inch by quarter inch. So that’s all I got.

CF: Let’s look at some of your paintings in depth. Some of your paintings have a little pearl on them, what is that?

CB: Yeah, it’s a circle, a three-dimensional circle, and it’s a symbol of pure perfection. It’s not in everything I do, but it shows up in a lot of different pieces.

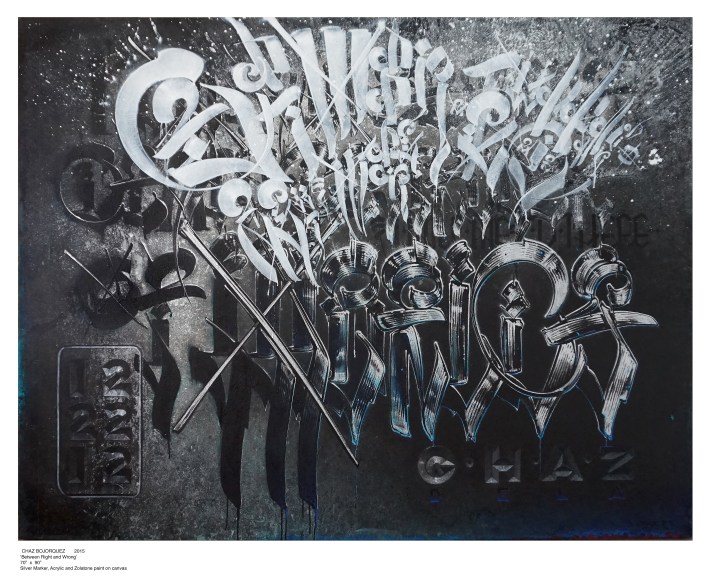

One painting that I just finished, it was an idea about the Mayan calendar, about the transition from the ancient, old, epic era and the transition to the new one. That ended on December 21, 2012, in my painting I had December 22, 2012, so it’s about the next thousand years. I wanted it to make a statement for the next era. It had to be something so positive and important to me, I had found the poet Rumi. He was a poet born in 1209, and his poetry was so personal, and so loving, and so timeless. I found a quote that I used “between right and wrong, there is a garden, and I will meet you there.” So that went into the painting, speaking about the future of humanity.

Investigating Rumi more, I found another quote, which I thought related to graffiti, “we come spinning, scattering stars”, sort of like we come destroying everything, but in our wake is knowledge and jewels. So that’s what this other painting inspired by Rumi is about.

I also had a big show at the Plaza de La Raza Gallery. I said, hey man what’s going on with the end of the Mayan Calendar? So we had a big End of the World show. We had Aztec Dancers, we had torchlights, red carpet… it was a great opening. That was four years ago.

My paintings take between one and four years to finish. I will start them, come back, start again, come back. It takes me time to figure them out. I could never figure out what to write on top. It took me a couple of years before I found Rumi. Paintings start as an idea in my head, then that forms a vision, and then once I paint it, that’s first base. Then as we progress, the painting becomes the teacher. It tells me, Chaz, the voice is from this character. Put light on that, and darken everything else. This person or this word needs to be stronger. Make it bigger, sharper, darker, stronger. The painting becomes the teacher, and nothing leaves until it’s truly finalized. How many times do you do something, and you come back a few days later, a week later, and you see all the mistakes in it you didn’t see the first time? It takes guts and balls to keep on fixing it and fixing it. It won’t leave the house until it’s done. These paintings are teaching me, they are personal images of self-discovery and torture… it’s not easy. I suffer with my work.

But remember, one powerful image can make your career.