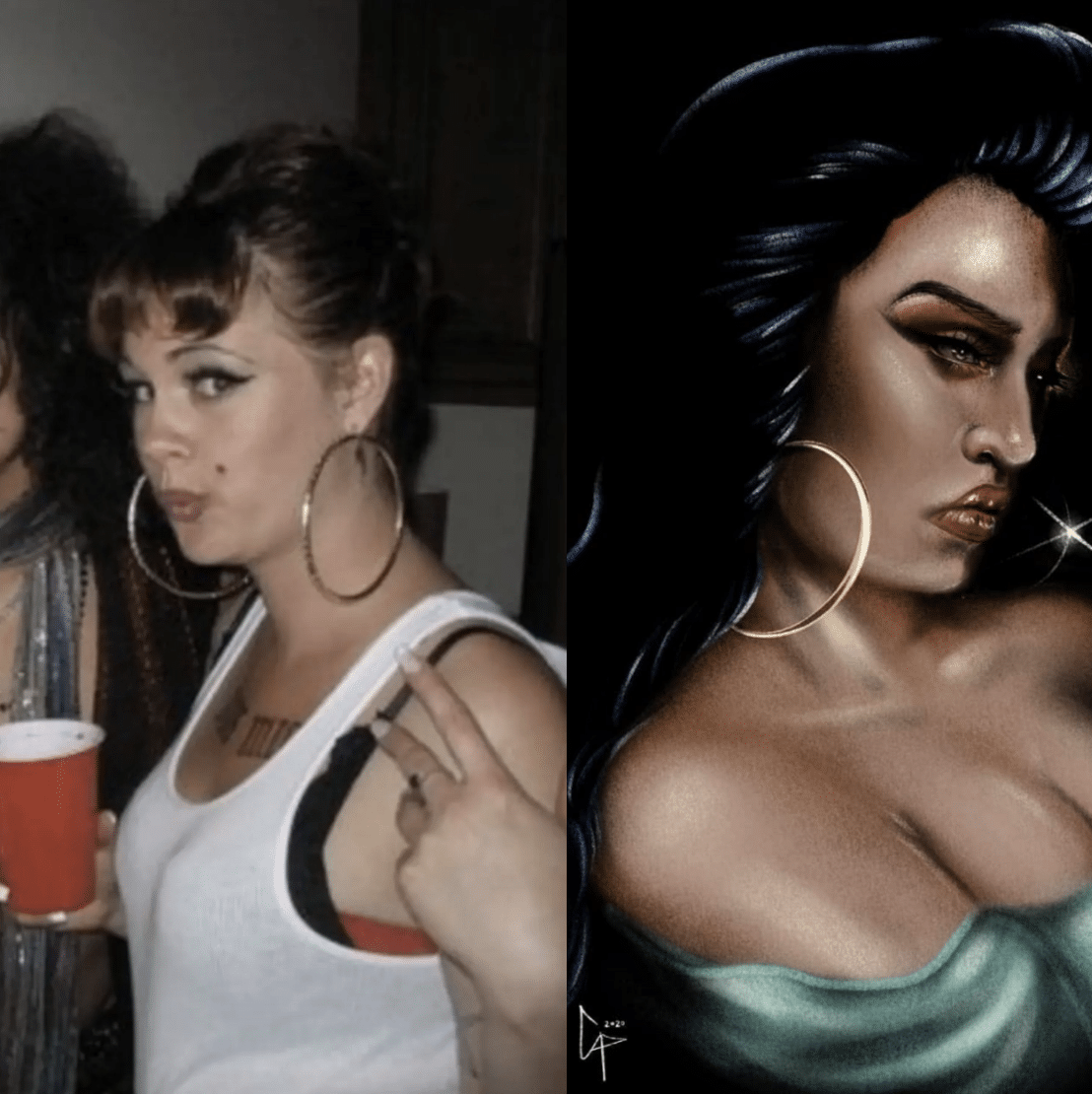

[dropcap size=big]T[/dropcap]he big, gold hoop earrings.

The tight white tank top, otherwise known by a messed-up moniker for a domestic abuser.

The excessive eye makeup, tattoos, flash of fingers, and a smirk for the camera.

Just another White girl dressed as a “chola” for Halloween? But was she? And why does it matter right now, anyway?

On June 8, journalist Yashar Ali tweeted an old MySpace photograph of New York Times food columnist and cookbook author Alison Roman “dressed up as a Chola” for a 2008 party. In her reply, Roman tweeted that her Halloween costume was not of a chola, but an “SF-inspired Amy Winehouse.” She acknowledged and understood how her costume “reads as culturally insensitive” right now before apologizing for her youthful error.

Nevertheless, media outlets from Page Six to the UK’s Daily Mail ran stories of Roman’s “offensive ‘Chola’” costume and her Amy Winehouse defense. Roman’s photograph appears just weeks after she came under fire and had to apologize for her critical remarks about Chrissy Tiegen and Marie Kondo. Roman was called out by Roxane Gay and others for showing “disdain” for women of color, not a good look coming from someone in Roman’s position and given the overrepresentation of white women in food media.

Now, Roman finds herself again having to apologize for an offense against Brown women, this time taking responsibility for inadvertently posing as a chola. The cholafied Winehouse photo of Roman comes on the heels of another photograph that showed Bon Appétit’s former Editor-in-Chief Adam Rapaport dressed in brownface as a “Puerto Rican” at a 2013 Halloween party.

Like many institutions right now, elite food media outlets find themselves facing an intense reckoning and opportunity for self-reflection during this time of mass support for the Black Lives Matter movement and its immediate anti-racist aims. And like every pop culture moment or story that’s made news cycles, context is everything.

As a queer Chicana writer, scholar, and profe in literature and cultural studies, I think about language and representation all the time. For years at area UC and CSU campuses, I’ve taught about “cultural appropriation”—especially in music, food, and sports—in my pop culture, gender studies, and Chicanx-Latinx studies classes.

Cultural Appreciation versus Cultural Appropriation

It’s one thing for students to read bell hooks’ great 1992 essay, “Eating the Other,” and consider the distinctions between “cultural appropriation” and “cultural appreciation.” That’s the difference, say, between Gwen Stefani affecting chola-ness in the video for her 2004 song “Luxurious” (featuring Slim Thug) and devotees of Chicano and Chicana subcultural practices like lowriding and donning chola style in Japan. It’s another thing to connect such actions to larger histories of colonialism, or to account for the differences and reasons behind each of these “chola” cultural and stylistic expressions that appear outside of the original contexts and communities that invented them.

The harder questions require us to do more than just ‘call it out’ and name the costume offense as “cultural appropriation.”

Such cases of ‘chola appropriation’ force us to move past yes and no, good or bad, ‘is it or isn’t it cultural appropriation’ questions to ask harder and more demanding questions that don’t have neat answers and that requires thought and attention to nuance. More importantly, the harder questions require us to do more than just ‘call it out’ and name the costume offense as “cultural appropriation.”

Because for too long, I’ve heard students, teachers, university administrators, and people in the general public use “culture” euphemistically when they really mean “race” or non-white “ethnic difference.” From a profe’s perspective, I’m more interested in how Roman’s Halloween costume photo and its circulation expose what most of us already know—that dressing up as any kind of ‘ethnic Other’ is obviously wrong—but more so, what those with access to elite media power still must learn about their seemingly innocuous acts.

But ‘ethnic’ and racialized costumes, as commodified stereotypes, perform another kind of violence that amounts to cultural co-optation, denial, and the gradual erasure of a history, culture, community, or a people.

Can we now say that dressing up as a chola, or in Brownface or Blackface, or ‘ethnic/cultural’ anyone as a Halloween costume or frat party outfit or school themed function or Coachella or a football game is not some innocent or harmless act done in good didn’t-meant-to-hurt-anyone fun, but another form of racist violence?

Whoa, profe. Really?

A Halloween costume is one thing. It’s definitely not the same as that white cop’s knee on George Floyd’s neck. I get it. And Roman is certainly not the first Halloween or frat-party goer to throw on hoop earrings, draw on fake tattoos, put on black bold eyeliner, and wear tight white tanks with baggy pants to affect a tough “chola” look, even if it is explained away by calling it an “SF-inspired,” and thus a racialized “Latinx,” version of Amy Winehouse. (By the way, an anonymous source came forward to L.A. Taco alleging that the Amy Winehouse excuse Roman is using was fabricated by her publicist.) No, that’s not the same thing as a cop killing you on the street, or an ICE agent taking your mom and throwing her into a van in front of you to deport her or detain her indefinitely. But ‘ethnic’ and racialized costumes, as commodified stereotypes, perform another kind of violence that amounts to cultural co-optation, denial, and the gradual erasure of a history, culture, community, or a people.

A brief history of the gender-blending chola aesthetic

Like all fashion, the clothing and accessories that comprise “chola” style have unique histories that attest to a population’s resistance to interlocking systems of racist, sexist, and economic oppression in the U.S. Plenty of Chicana and Latina scholars have written about the rich cultural and political practices of race-gender-identity construction through fashion, style, and self-adornment.

According to Chicana film scholar Dr. Rosa Linda Fregoso, the pachucas of the 1930s and 1940s are the predecessors of the cholas of the 1970s and 1980s. Pachuca style came to prominence in Los Angeles and other Mexican American urban areas in the U.S. southwest during World War II.

In her 2009 book, The Woman in the Zoot Suit, UC Santa Cruz professor Dr. Catherine S. Ramírez writes about the distinctly working-class pachuco and pachuca style that is rooted in Mexican American urban identities and gendered experiences shaped by the patriotic demand to conform to World Word II-era ideals of whiteness and the nation. “[Pachucas’] attire, hairstyles, and use of cosmetics were not read as proof of conformity,” writes Ramírez.

“The chola identity was conceived by a culture that dealt with gang warfare, violence, and poverty on top of conservative gender roles. The clothes these women wore were more than a fashion statement—they were signifiers of their struggle and hard-won identity.”

Ramírez also explains how pachucas transgressed feminine style norms when they wore ‘masculine’ clothing like men’s shirts, white tank tops with suspenders, and trousers with their dark lipstick and big hair. As Barbara Calderón-Douglass writes in her 2015 Vice essay, The Folk Feminist Struggle Behind the Chola Fashion Trend, “The chola identity was conceived by a culture that dealt with gang warfare, violence, and poverty on top of conservative gender roles. The clothes these women wore were more than a fashion statement—they were signifiers of their struggle and hard-won identity.”

This gender-blending look of working-class, feminine hair, and makeup styles with masculine clothing items comprise what we recognize as an unmistakable “chola” style that’s been imitated and replicated in pop culture for the last thirty years, from films like Mi Vida Loca (1993) to Montebello native Chelsea Rendon’s “Mari” character in STARZ’ Vida (2018), and especially by white pop singers like Madonna, Gwen Stefani, and to an extent, Amy Winehouse.

In my classes, students love to also debate the ‘levels’ of offensiveness of a particular example of cultural appropriation, as if some acts aren’t as bad as others. Even Rihanna donned a flannel shirt, bandana, and fake face tattoos for her chola costume at a 2013 Halloween party. Does it make a difference if Rihanna, a black Barbadian islander pop singer, fashion icon, and makeup maven, ‘dressed up’ as a chola? Or, in discussing “yellowface,” is Janet Jackson’s use of “Asian” imagery and dancers in her video for her 1993 hit “If” different from Gwen Stefani’s 2004 video for “Harajuku Girls” or Katy Perry’s “geisha” performance at the 2013 American Music Awards?

The ‘chola’ style in particular and ‘Latina’ style more broadly—think clothing lines by Jennifer Lopez, Sofia Vergara, and the late Selena—are easy to “glomp onto” because they’re so ethnically marked and very pervasive in dominant representations in media and pop culture.

According to Dr. Stacy I. Macías, a scholar of queer Chicana-Latina femininities and professor in Women’s and Gender Studies at Cal State Long Beach, the ‘chola’ style in particular and ‘Latina’ style more broadly—think clothing lines by Jennifer Lopez, Sofia Vergara, and the late Selena—are easy to “glomp onto” because they’re so ethnically marked and very pervasive in dominant representations in media and pop culture. “The look is easily available for consumption and reproduction without any thoughtfulness,” Macías told L.A. Taco. “That’s what a stereotype is.”

The individual accouterments of “chola” style—bandana, baggy pants, tight white tank, lipstick, eye makeup, big earrings, and other accessories—are thus easily accessed and assembled accordingly into an effortless, thoughtless costume any time, anywhere, and presumably without any trouble by the wearers in the day to day world.

Dressing up and privilege

In other words, wearing such a costume is a form of privilege in all kinds of ways. In a 2014 essay published in The Guardian, Julianna Escobedo Shepherd argued that wearing “chola style” is a “fashion crime” of cultural appropriation because “[p]rivileged people want to borrow the ‘cool’ of disenfranchised people of colour, but don’t have to face any of the discrimination or marginalisation that accompanies it.”

L.A. Taco reached out to Roman for a comment about her photograph. In an email, Roman said that she “had the materials” like the “makeup, tank top, and earrings [to] cobble together some sort of Amy Winehouse-ish vibe.” That makes sense given Winehouse’s profile at the time and this photo of Winehouse wearing said ‘materials.’

She attributed the “SF” inspiration to having lived in San Francisco in the 2000s and seeing “women of all cultures emulat[ing] Latinx styles in their daily dress at the time.” Roman continued, “I didn’t realize it was appropriation at the time, but looking back now, I of course recognize that it was.”

Roman’s observation about how easy it is for all kinds of women and people to “emulate Latinx” styles serves Macías’s point about how fashion trends circulate as commodity culture, whether in pop culture or in urban areas like San Francisco. The city’s Mission District is a kind of “ground zero” of gentrification where Mexican American and Central American immigrant families have been disproportionately displaced. Therefore, Roman’s inspiration comes most likely not from the lived experiences of actual cholas or barrio mujeres that she hung out with and befriended, but from street fashion, film images (think Benjamin Bratt’s La Mission), and dominant pop culture at large.

Rapaport and Roman aren’t the first, nor will the be the last, high profile person to have old photos of them in “culturally insensitive” (i.e., racist) Halloween costumes from years past come back to haunt them in the present, prompting the predictable apology and pleading of youthful ignorance and carelessness on the matter.

“We imagine seeing [chola fashion] all around because it’s so pervasive in these other ways,” says Macías, “But we don’t actually see it embodied by ‘quote-unquote cholas’ every day on the street. You might see a version of immigrant, working-class femininity in those areas at that time that’s not necessarily going to be stylized as ‘chola.’ And the chola is definitely not ‘Latinx.’”

Arguably, Roman’s choice of a Halloween costume in 2008 might not be international news were it not for Rapaport’s photo that prompted his resignation as Bon Appétit’s Editor-in-Chief. Both of these particular white people are part of powerful East Coast media institutions that wield incredible power as food industry publishers and trendsetters. Yet, the timing of Ali’s tweet about Roman’s “chola” costume ties it to Rapoport’s Brownface move.

Rapaport and Roman aren’t the first, nor will the be the last, high profile person to have old photos of them in “culturally insensitive” (i.e., racist) Halloween costumes from years past come back to haunt them in the present, prompting the predictable apology and pleading of youthful ignorance and carelessness on the matter. Just last week, Eater LA published a report ousting a popular French restaurant owner in the city for dressing up in Blackface in 2011 as Lil’ Wayne.

A national awakening

Racism and cultural appropriation is nothing new in the food publishing and restaurant world, either. Meaning, White chefs and writers have personally benefited from the groundwork laid by people of color for centuries, since their European ancestors looted and pillaged indigenous lands for their own wealth. Some of them are finally responding to decades-long critique. Just ask Black food activist Bryant Terry about “Thug Kitchen.”

We’re at a point where conversations around “cultural appropriation” just don’t cut it anymore. Yes, no, so what, y que? It’s too easy, now, to explain away and apologize. In my book, wearing Brownface or an ‘ethnic’ Halloween costume is not much different from the sports fans who foolishly wear feathered headdresses, red face paint, and wield floppy foam tomahawks at Braves, Seminoles, Indians, or Washington football games.

Cholas are political embodiments of cultural agents in Chicanx communities who celebrate chola form as brown female power. Their purposeful embodiment as cholas and homegirls, and their commitment to the betterment of their barrios has been practiced throughout generations.”

In the end, the big gold hoops, dark lipstick, tight white tanks, fake tattoos, and flashing fake gang signs to play “chola” at a Halloween or frat party or even in a novel like American Dirt serve not to honor but to demean, mock, and flatten rich cultural expressions into plastic stereotypes, while lazily playing into the circulation of racist and gendered images of Chicanas and Latinas.

Rather, we can think of the founders of La Chola Conference, who proclaim that “Cholas are political embodiments of cultural agents in Chicanx communities who celebrate chola form as brown female power. Their purposeful embodiment as cholas and homegirls, and their commitment to the betterment of their barrios has been practiced throughout generations.”

This latest ‘chola’ incident is just one of many examples of how media coverage and popular culture responds to this incredible Black Lives Matter movement, including the national awakening or reckoning that seems to be taking place around structural racism and violence in all its faces and forms.

And yeah, it’s messed up to dress up as a chola if you aren’t one for real. It’s pretty racist if you do.

Author’s note: special thanks to Dr. Stacy I. Macías, Dept. of Women and Gender Studies at Cal State Long Beach, for her insights and comments on this subject.