[dropcap size=big]T[/dropcap]hough officially just a few months old, the Banc of California stadium in Exposition Park holds more than a half-century of history. The stadium sits atop what was once the Los Angeles Sports Arena, whose history is immortalized on dozens of plaques along the new stadium’s walkway. These plaques are a reminder of the days when the area hosted some of the biggest names in music and sports. There’s a plaque dedicated to Pink Floyd’s numerous shows there in the 1970s, another for the years the Lakers balled at Expo, and one for the Los Angeles Aztecs, L.A.’s original soccer sensation.

The plaque honors the Aztecs’ indoor soccer team, which played its final year at the Arena in 1981. Meanwhile, the Aztecs’ professional, outdoor squad played at the Memorial Coliseum that same year. Their time at Expo Park was brief but the plaque is a reminder of the days before Major League Soccer’s foothold in the country when soccer was still an alien concept to most people.

But the fact is, the history of L.A. soccer is long.

The first professional soccer teams in the city were the Los Angeles Toros of the National Professional Soccer League and the LA Wolves (owned and operated by English team Wolverhampton Wanderers) of the United Soccer Association. They both debuted in 1967. The leagues merged the following year to create the North American Soccer League. The Toros moved south, to San Diego, while the Wolves lasted just one season before dissolving.

Fast-forward to 1974. Jack Gregory, a lifelong soccer fan, licensed doctor and real estate financier, and a few of his soccer-loving friends put their money together and brought the national teams of Mexico, Poland, and others to the Coliseum to play in friendlies before the World Cup that summer in West Germany. The success of the games whetted his appetite for more — just in time for NASL commissioner Phil Woosman to announce an expansion plan for the league.

“L.A. was open, so I gave him a phone call,” the now-retired Gregory told L.A. Taco. He agreed to pay the franchise fee, and when he hung up the phone, L.A. officially had a pro soccer team.

He and his wife named the team the Los Angeles Aztecs, not only as a nod to the majority-Mexican fans they hoped to win over, but also because they “wanted an aggressive team to show its steel.” Gregory felt the Aztecs had “a beautiful history of warriors” that the players could draw inspiration from and emulate on the field.

Gregory hired Alex Perolli as coach and Ricardo Ordoñez as his assistant coach. They put together a 28-man squad that represented more than 10 countries.

It was the first time a professional soccer final was televised nationally in the United States.

[dropcap size=big]T[/dropcap]he Aztecs debuted with four pre-season friendlies versus teams from Mexico’s Liga MX: Atlante F.C., Club América, C.F. Monterrey, and Pumas UNAM.

“We had a good following of the Latin community,” remembers Gregory of those early crowds, “but they were always rooting for the Mexican teams, not us!”

The Aztecs found immediate success. They averaged 5,098 spectators throughout the season — meager by today’s standards but a respectable one in the early days of pro soccer, and just under 3,000 of the league-wide average that year.

RELATED: Support Stories Like This & Become a Member of L.A. Taco Today!

Perolli’s crew burned through the opposition, and won the Western Division Trophy. Weeks later, they won the NASL Championship Trophy after they defeated the Miami Toros (unrelated to the former LA/SD team) after penalties. It was the first time a professional soccer final was televised nationally in the United States.

“It was one of the most exciting games of the season,” says Gregory, “because we tied the game in the last minute, three to three.”

That debut season would be the only year that the Aztecs ever won a title. Their sister indoor squad didn’t fare any better as they won a single division championship in their final year, 1981. Gregory sold the team after the first season. He and Perolli accomplished the goals they set for that first year and he wanted to focus on his medical career.

“It grew so fast that it grew right out of my hands,” he remembers. “I was a doctor and I was actively practicing and I could never have handled it after that.”

The new owners brought in Sir Elton John as a co-owner to promote the team.

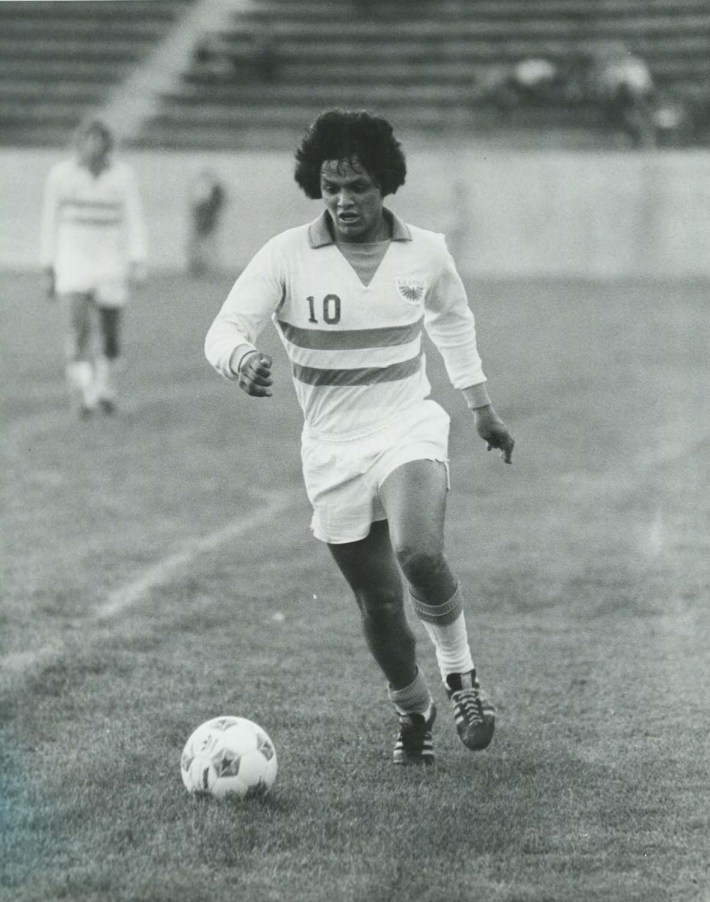

[dropcap size=big]A[/dropcap]s the years went on, the Aztecs featured a handful of local players who made the leap to the pros, such as UCLA alumni Jose Lopez of Santa Ana (by way of Mexicali) and Sergio “Cucharita” Velazquez of El Monte. Miguel Lopez (no relation) played at San Gabriel High School, Whittier College, and local semi-pro team South Bay United before joining the Aztecs. They were joined by Mexican players from Liga MX, such as Javier “El Vasco” Aguirre, well-known to fans of El Tri.

But the team also signed European icons that joined the team, on and off the field. The new owners brought in Sir Elton John as a co-owner to promote the team from 1975 to 1977.

North Ireland and Manchester United legend George Best joined in 1976. He and a few friends also owned and operated Bestie’s Bar and Restaurant (now known as the Underground Pub Bar & Grill) in Hermosa Beach.

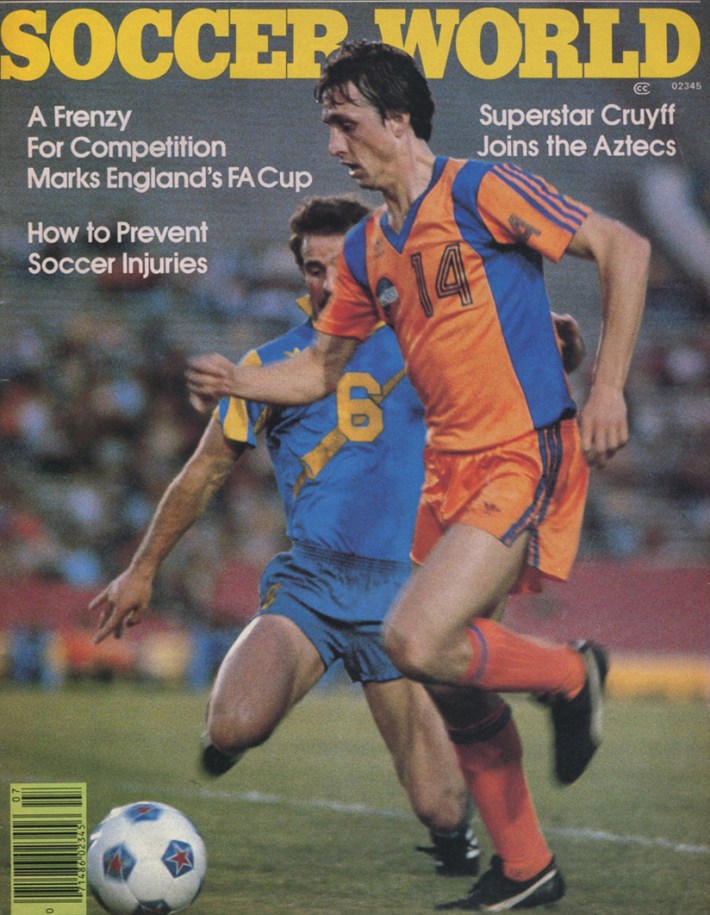

More important were the Dutch. In 1979, Rinus Michels arrived in L.A. as the new coach of the Aztecs, bringing along with him Johann Cruyff. Michels’ name is synonymous with the creation of Total Football, an attacking style of play where players constantly swap positions on the field, and Cruyff was his greatest disciple. Together, they led the Netherlands to the 1974 World Cup final. They also helped FC Barcelona fill its trophy case, as Cruyff thrilled fans worldwide with his gravity-defying, body-bending athleticism and technique.

Fans hoped Michels and Cruyff would replicate their success with the Aztecs. But Cruyff wore the Aztec jersey for just one season (he won the League MVP), and Michels coached the Aztecs for two seasons before returning to Europe.

RELATED: Who Are the ‘Real L.A.’ Soccer Fans? ~ A Look At the Growing Rivalry of Galaxy vs. LAFC

That reliance on foreign stars threatened the identity of the league, and stunted its stateside growth. Fans wanted to see NASL develop local, American talent that could raise the profile of the U.S. national team in the World Cup and other tournaments.

“Part of it is, I think, there were a lot of obstacles,” says Jose Alamillo, professor of Chicano/a Studies at California State University Channel Islands, by phone. “I think they hadn’t really figured out that formula. How do you cultivate a Latino fanbase?”

Alamillo points to numerous factors that contributed to the team’s identity issues. The Aztecs repeatedly switched venues. By the time they folded, they had played at Weingart Stadium in East Los Angeles College, Murdock Stadium in El Camino Junior College, the Rose Bowl, The Fabulous Forum, the Coliseum, and the L.A. Sports Arena.

Aztecs star Johann Cruyff helped FC Barcelona fill its trophy case.

The team and its Latino players should be applauded for the honest efforts they made to bring professional soccer to the region.

[dropcap size=big]O[/dropcap]wnership changed multiple times — Mexican television behemoth Televisa even had a stint. These owners had to fight the perception that soccer was a foreign sport, a situation exacerbated for a team named after an ancient and foreign civilization. When Terry Fisher signed on as coach for the Aztecs in 1975 he told the New York Times, “Too much emphasis on ethnic groups doesn't mean success in my book. Soccer is no longer a foreign sport and nobody can tell me otherwise.”

The Aztecs’ indoor team played its last home game at the Sports Arena on February 16, 1981, an 8 – 3 loss during the first round of the playoffs. The outdoor pro team played its final game that August at the Coliseum, an agonizing 2 – 1 first-round loss in overtime via penalty kick to the Montreal Manic. By the end of the year, Aztec owners announced the team would cease operations; three years later, the NASL would do the same.

Despite this, Alamillo believes the team and its Latino players should be applauded for the honest efforts they made to bring professional soccer to the region.

“I think they need to be recognized for their contributions,” says Alamillo, “for what they attempted to do. We need to learn more about them and it’s time that we recognized them.”

Long before the Los Angeles Galaxy would ever sign European stars such as Zlatan Ibrahimovic, before Chivas USA would attempt to woo a Mexican fanbase, and before the Los Angeles Football Club would settle at Expo Park, the Aztecs had attempted all that and more. Though ultimately unsuccessful, the plaque dedicated to the Los Angeles Aztecs is a small tribute that shows how soccer has now truly come full circle in L.A.

RELATED: El Súper Clásico Is This Sunday at The Coliseum, Are You on Team Pambazo or Team Torta Ahogada?