Welcome to L.A. Taco’s new column, “Barrio Wisdom.” In this new series, we follow the streets-meet-academia wisdom of Dr. Álvaro Huerta, a professor at California State Polytechnic University, Pomona. In this installment, we learn how growing up in the inner-city housing projects can teach you to be a better person.

[dropcap size=big]N[/dropcap]ietzsche warned me about gazing too long into the abyss, but I didn’t listen. It gazed back into me. After spending my early years with extended family in Tijuana (Baja California) and Hollywood (Alta California), I spent my formative years with my immediate family in East Los Angeles’ notorious Ramona Gardens public housing project—better known as the Big Hazard projects, named after the dominant gang.

During the ten-year period that we lived there, it was considered one of the most dangerous neighborhoods in the country. From gangs to drugs; from police abuse to housing authority harassment; from drive-by shootings to death; from high school drop-outs (or push-outs) to chronic unemployment; from abject poverty to welfare. If you weren’t raised in the projects and lived through its darkness, just “sit down”—to quote the street philosopher and rapper, Kendrick Lamar—and listen.

Defend yourself

If you’re white and move into the lily-white suburbs, you’ll be cordially greeted with a “hello neighbor” and given a beautiful basket of fresh fruits, gourmet cheeses, and crackers. In the case of my brother Salomón and I, when moving into the projects, we were “warmly” greeted by a bunch of Chicano kids, seeking to officially induct us into the neighborhood with arranged fights.

Fortunately, as an eight-year-old, Salomón mimicked the best Bruce Lee kung fu moves he would see in films, and his opponent quit without throwing a punch. When it was my turn, as a six-year-old, I followed in his footsteps and raised my arms in victory. As we were welcomed into the neighborhood, we learned a hard lesson with this rite of passage: To survive in the projects, you must be able to defend yourself. While I don’t expect outsiders to understand, I’m also indifferent to individuals who don’t want to learn about the norms and traditions of the mean streets of East Los Angeles

We are not brown savages and don’t need you to save us

I will never forget the summer when the white, born-again Christians arrived in their white buses into the projects to “save” us—poor, Catholic Chicana and Chicano kids. To lure the neighborhood kids, they enticed us with free field trips, money, and food. These invaders didn’t ask permission from our parents; they just took us. As a 10-year-old, I couldn’t resist all of the goodies. Once on the bus, I recall singing Christian songs, where the white escorts tossed dollar bills to the best singers, like brown monkeys doing tricks for treats.

One hour later, we arrived at a large auditorium with an all-you-can-eat buffet. I loved the desserts, especially the chocolate cake with white frosting. After lunch, the blond, blue-eyed preacher delivered a sermon, which I didn’t understand one word, where I kept thinking: “Where’s the Virgin de Guadalupe?” He then instructed us—between 50 to 75 brown kids—to go into a room in small groups. Once there, they told us to take off all our clothes and put on blue plastic gowns, similar to hospital patient gowns. They then led us inside a large pool, where, one-by-one we were fully dunked into the water and baptized by the preacher. I didn’t feel born again. Looking back, I wonder what the white savior preacher was thinking: “Let’s go to the jungle of East Los Angeles and save these brown savages!”

You don’t have to breathe it in

While former Presidents Bill Clinton and Barack Obama inhaled marijuana during their youth, when I was first offered to smoke at 11 years old, I didn’t. On a hot summer night, I was playing basketball at the gym, when one of my childhood friends asked me (more like told me) to follow him outside to meet up with his older brother.

I originally thought I was going to get jumped since his brother was in the gang. While I didn’t show any fear, adhering to the rules of the projects, I was happily surprised that they actually invited me to smoke. Offering sage advice, my friend said, “When you inhale, hold your breath so it gets into your lungs!” I quickly recalled a movie from Murchison Elementary School, where smoking cigarettes caused black lungs. While pretending to smoke, as they passed the joint, they got high. Ten minutes later, I returned to the gym to shoot hoops. Given the prison-like conditions we lived under, being treated like wards of the state, as rational actors, temporarily escaping from a harsh reality makes life bearable.

Protectors or Oppressors?

In the lily-white suburbs, the police officers (or cops) live up to their motto of “To protect and to serve.” In the projects, they behave like an occupation force in a foreign country. As poor, brown kids from the projects, when approached by the cops, we knew the drills. When walking, stop immediately, get on knees and put hands behind your head. When standing near a wall or building, turn around spread legs and put hands against the wall. When driving, turn off the engine, put hands on the steering wheel and don’t talk back.

Like “good” Mexicans, be obedient! “Yes, officer. No, officer.” While driving my navy blue ’67 Mustang (a gift from my sister Catalina) as a 16-year-old, I was pulled over by the cops. The driver got out of his car, yelled expletives, walked towards me and pointed his gun ten-feet away from me. My crime: making a rolling stop! One wrong move on my part, like demanding my civil rights, and I could’ve been killed.

Using the shame of poverty to fuel yourself

There’s nothing romantic about being poor, despite what Gandhi preached and practiced in India. When my mother Carmen—a domestic worker for our 40 years—sent me to La Paloma Market, I was always embarrassed to use food stamps. Back then, they came in a booklet with Monopoly-looking money to purchase groceries. (Now, the government issues EBT cards.) In retrospect, I shouldn’t have been embarrassed since all of my childhood friends were also on food stamps and welfare. Speaking of being ashamed, when my best friend and I visited the amusement park Six Flags Magic Mountain in our teens, we agreed to say that we lived next to General Hospital, if we met anyone. It was like the scene in La Bamba (1984) when the popular Chicano singer Ritchie Valens was ashamed to tell his white girlfriend Donna where he lived—a barrio in Pacoima. Now that I’m older and wiser, when conservatives try to make me feel ashamed of growing up poor and on welfare, I always ask them, “What about welfare in the egregious forms of tax breaks and subsidies for elites, agribusinesses, and corporations?”

Your roots are your strength

Since abandoning my family and homeboys to pursue a degree in mathematics at UCLA as a 17-year-old freshman, over the years, I grew to appreciate and defend where I came from without apologies. Whenever I mention that I was raised in the projects in East Los Angeles, people usually ask, “How come you never joined a gang?”

With a straight face, I quickly reply: “Actually, I submitted my gang application, but it was rejected because I was too thin to defend the neighborhood!” Jokes aside, if I had the fearless mentality and physical attributes of many of my childhood friends, where they joined the gang, instead of spending many years in higher education, I would’ve been doing time at Folsom and San Quentin.

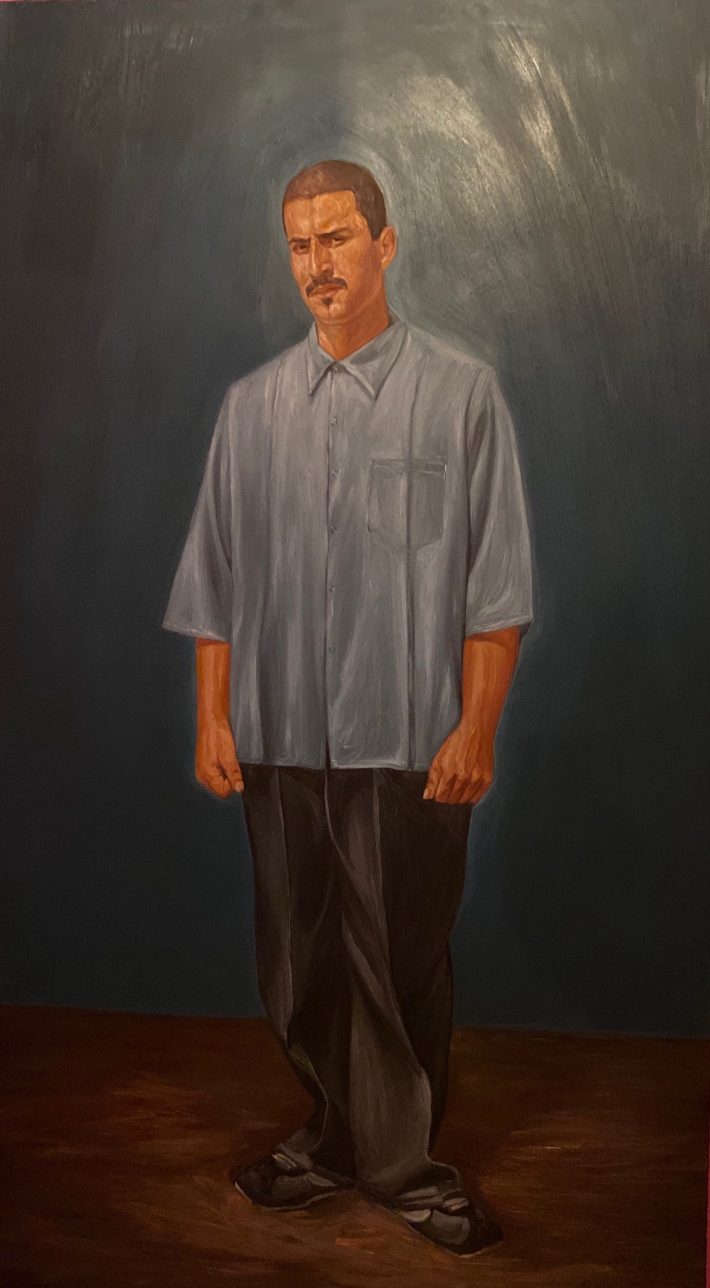

While I don’t romanticize gangs, I also don’t cast judgment on my childhood homeboys, where the odds were against us from the start. For me, it helped that I excelled in mathematics, where, like my brother Salomón who studied (and mastered) art at ArtCenter College of Design (B.F.A.) and UCLA (M.F.A), my special skill was my ticket out of the projects. I only wish that everyone else from the projects had (and has) the same opportunities to pursue higher education to succeed.

Don’t blame the victims, blame the systemic conditions

When we analyze and try to understand the bleak plight of residents in public housing projects throughout the country, let’s not blame the victims. Instead, let’s put the blame of their harsh conditions on a capitalist society that houses mostly brown and black bodies in oppressive environments with hopeless and traumatic outcomes.

American society—past and present—has neither been fair nor just to brown and black people. Structural racism. Racial segregation. Divide and conquer. Police abuse. Concentrated poverty. State surveillance. !Ya basta!

If we, as a nation, invest in these communities—our communities!—like “we” do to maintain the military-industrial complex, which profits from endless wars, like in the most recent case of Iran, we would immediately end the despair of los de abajo in America’s barrios and ghettos.