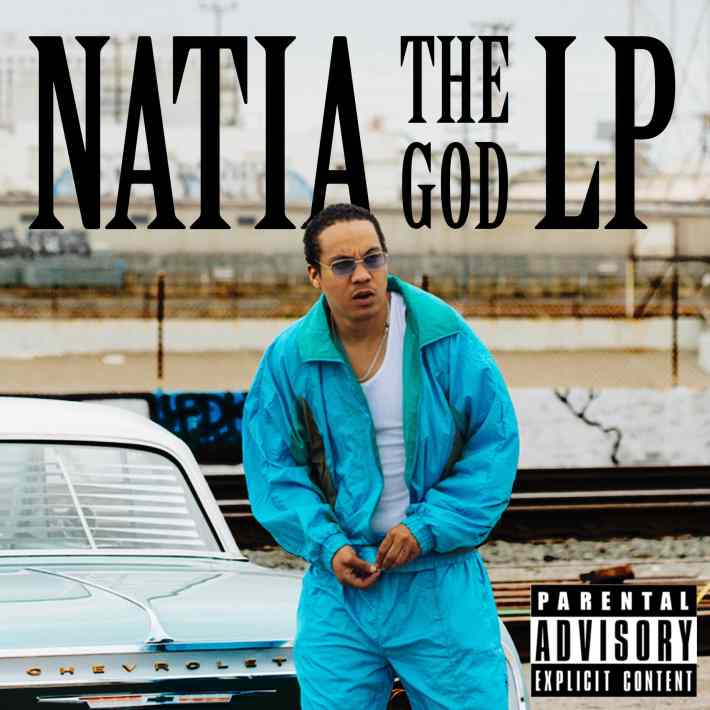

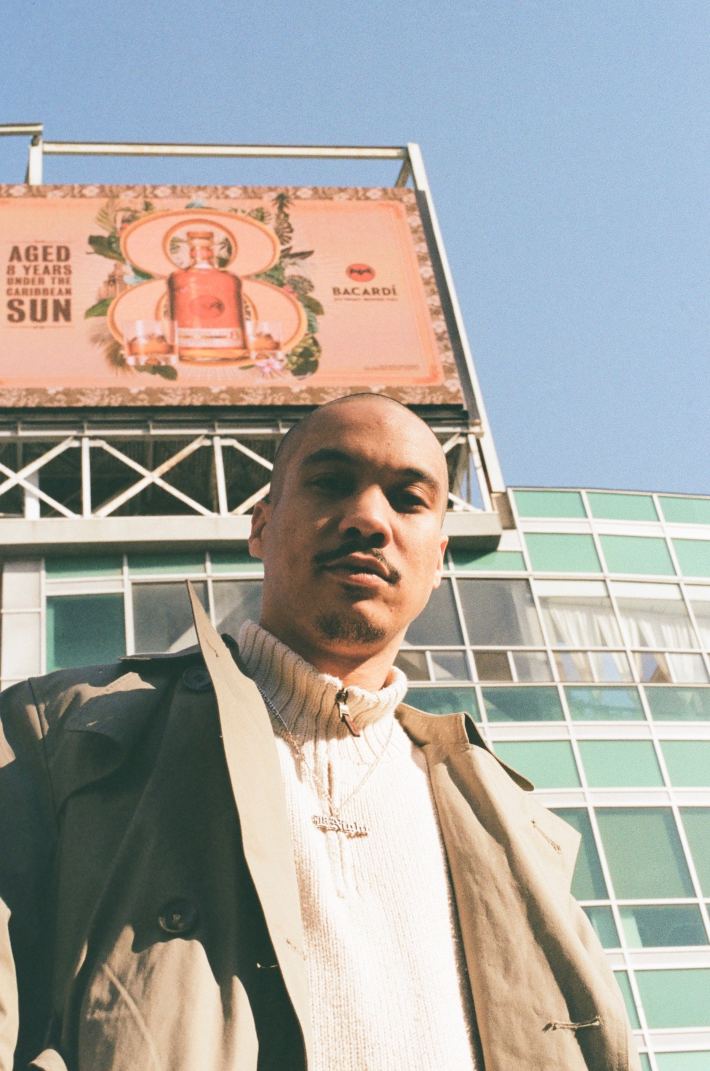

[dropcap size=big]O[/dropcap]n several occasions separate from skating in the area, Natia had slept outside of Koreatown’s 3700 Wilshire Boulevard. It was here that I met Natia to talk about his new album, ‘Natia the God - LP.’

Nearby, a patch of forest-green conifers with pendulous branches look like a glitch amongst the greys of marble and asphalt; they offer respite from L.A.’s evergreen sunny days in a neighborhood that overheats from a lack of shade trees.

After soaking in the familiar, Natia jabbed through the silence with his deviant sense of humor. “Sometimes at the end of the night I just had to find a place like this,” he told L.A. Taco, in reference to his sleeping spots when he was homeless for most of his 20s. “Koreatown, this place of wonders...where the world is my restroom.”

Natia’s in an apartment somewhere near 6th and Western in Koreatown now. Before that, he was kicked out of an apartment in Downtown that was available on a sublease. Upon the sudden displacement, he sought relief in Skid Row, sleeping in the car with his girlfriend for a period of time before the two of them searched for subsidized housing.

One year later, Natia feels safe and settled in. His focus has been on music all year. That culminated in one of his most personal tell-all albums to date, grappling with homelessness, schizophrenia, and how to come up for air from the poverty line.

The new album comes two years after his debut ‘10k Hours.’ At the time, Natia’s nightly routine was to retire to quiet places near the parties he was at. “I always used to hate the end of the night,” said Natia. “Everybody knew I was homeless so they was [sic] always like ‘So, what are you about to do?’ You know...wherever I was, that’s where I’m gonna go.” That resolve would take him to a public tennis court in Westchester, a car in Skid Row, or the very Wilshire Park ledge on which we sat down to talk.

From Skate Videos to His First Album

Born Natia Maluia, Natia grew up in North Inglewood and got his shine as a regular appearance on DeliStatus, a skate channel on YouTube popular for their edits of sessions with local skaters (the spot where we chatted was etched into skate history when legends like Chad Muska and Andrew Reynolds dragged their wheels along the ledges of the thick concrete slabs that frame the courtyard). At some point, he started dropping freestyles for the channel, too, a talent he had picked up in high school after becoming obsessed with Eminem’s book ‘Angry Blonde.’ After clacking and sliding through his rhymes on camera, Natia caught more buzz when Earl Sweatshirt shared his song “The Wrong Way” on Twitter in 2014. Since then, he had been trying to make a serious living with his music. Finally, he feels as if he’s things are falling into place.

From the jump, Natia is getting into a scuffle on ‘Natia the God - LP.’ “Chapter 1,” dashed with frenetic dialogue, is a Scorsese moment written from the point of view of a stylish mafioso-playa embroiled in a Vegas street racket. The “Chapter” intermissions are fun, for they hark back to the days of Raekwon and Ghostface’s pummeling body of work, which Natia cites as a big inspiration.

His voice sounds pinched and weary on his most revealing songs like “Bring the Pain” and “Voices,” but can glide into a paradisiacal flow on tracks like “Chapter 2.” Though a resolutely L.A. rap album, ‘Natia the God - LP’ would not be without the storytelling elements of ‘Only Built for Cuban Linx…’ and ‘The Eminem Show’ that influenced Natia.

‘Natia the God - LP’ is the most honest Natia has been about where he holds himself most accountable.

Even when Natia speaks, he repeats for emphasis or grabs the words that make you feel what he feels. When asked what was the most difficult part about living on the streets, Natia looked down at his bare arms. “The one thing that still really gets me is the cold. The hairs just shoot up,” he said while gesturing to his arm. “Whenever I’m cold I feel like I’m homeless. Every time, it reminds me of being out there. Every time.”

‘Natia the God - LP’ is the most honest Natia has been about where he holds himself most accountable. He affirms all the ways that he’s been distracted on “Wrong Way, Pt. 3.” In a bedside prayer to God, he dives into his recent bouts of temptation, substance use, and avaricious ambitions (“Money is the root and it make all of us hate / Shit I’m evil too I need 0’s in my bank / All of these demons it is so hard for me to shake / I think I need them I think they help me create”).

“Every time I try to catch up, I f*** up,” said Natia, “and then I make those songs when I f***ed up.” “That’s how I stop doing things the wrong way. There will probably be some more, until I die.”

For what it’s worth, none of Natia’s sins on “Wrong Way, Pt. 3” sounds like mistakes. His murmurs to God reckon with not “getting it right” at the behest of society. He was kicked out of his mother’s house in his late adolescence, which began a series of difficulties that prioritized his survival before privileges like a stable career. We created a system of right and wrong ways to move through L.A.–let alone America–that rewards people who happened to make “good” choices: finish high school, choose a college, find a stable job, and so forth. We feel in the wrong when we don’t. We pay for it, literally, when we don’t.

Between Homelessness and Being a Young, Creative Professional in L.A.

Being homeless is expensive. Earlier this year, the Los Angeles City Council reinstated an ordinance that bans sleeping overnight in vehicles in residential areas. Those who do not abide receive a ticket that starts at $25 then increases by $25 for every repeat offense. The lives of unhoused residents are also constantly being tested by the legal system. The Supreme Court chucked the Martin v. Boise case earlier this week; the case looked at fining people for violating ordinances that ban them from sleeping on sidewalks and public property if no other shelter is available. Though a win for its residents, Los Angeles still finds and perpetuates ways that make people feel banished or neglected.

“Just care about your human companion who’s next to you. Don’t give no type of thought to it other than that they’re a human being.” Then, he paused. “I feel like everybody knows that already, but we’re going to have to tell these people again.” It’s true. We wouldn’t be mourning the daily deaths of unhoused Angelenos if the City were taking that advice.

It is also expensive to be a creative professional in Los Angeles. Independent artists can book a studio in L.A. for upwards of $500 an hour. For engineering and mastering work, they have to shell out anywhere from $350 to $1200 depending on the volume. Take into account that many independent artists are dropping new singles or bodies of work several times a year due to the demands of the industry. For someone like Natia, who dropped two EPs on top of his album in 2019, an independent artist could be looking at spending thousands of dollars per year, all while also trying to stay housed in L.A.

This year’s homeless count conducted by Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority recorded a total of 582 unsheltered residents in Koreatown, up almost 79% from 326 in 2018. 208 of these residents live on the streets, 122 live in vehicles, and 93 of them live in tents. Since the count, there have been disastrous incidents of residents around the city who are dying from neglect or living under threat of losing their space. Natia beat devastating statistics by finding housing in Koreatown.

There’s a moment where he’s deeply locked into his freestyle and the lens flare from the afternoon sun puts a haze over the nearby palm tree and townhouse, a housing option once common in Natia’s Inglewood. It’s a candid slice of L.A. life.

Under a roof, Natia is focused on more music; he hinted at a new project coming as early as January. He wants to keep going until he finds the label and paychecks that let him live out absurdly hilarious displays of wealth. “I think about going to Goodwill and spending two racks in there,” he said, “Or going to Ralph’s and grabbing that one orange and all the oranges fall and you go ‘Oops, my bad, I’ll pay for them. Here’s $200 for each orange.’”

Just Care

Natia also wants to help the homeless and, in general, give away more to people and invest in ideas and stocks. In the meantime, the best advice he has is one that bears repeating. “Just care,” said Natia. “Just care about your human companion who’s next to you. Don’t give no type of thought to it other than that they’re a human being.” Then, he paused. “I feel like everybody knows that already, but we’re going to have to tell these people again.” It’s true. We wouldn’t be mourning the daily deaths of unhoused Angelenos if the City were taking that advice.

Natia hopes to get back into freestyling in 2020 as well. He’s masterful at it. Two minutes into an old video of Natia going off the dome on DeliStatus, there’s a moment where he’s deeply locked into his freestyle and the lens flare from the afternoon sun puts a haze over the nearby palm tree and townhouse, a housing option once common in Natia’s Inglewood. It’s a candid slice of L.A. life.

Natia has a way of making living seem cinematic, whether it be in Koreatown or Inglewood. It’s worth noting that Inglewood is also losing housing stock in favor of franchises and commercial buildings; like Koreatown, it has not seen affordable housing built in almost five years. The only visible “wrong way” in Natia’s story is the one that keeps people from living anywhere.

It was around 3 PM when Natia and I wrapped up. By this hour at this time of year, the sun is setting behind Koreatown’s new glassy, tall buildings. The grass lost its bouncy green hue as soon as grey clouds swallowed the sky. Outside with Natia, I got goosebumps from a stinging gust of wind. I asked him how he’s been doing the past few days with the December cold.

“Oh, I don’t know,” he laughed. “I’ve been in the house. I’ve been in the house.”