Editor's note: This piece was originally published in the Los Angeles issue (No. 21) of Lucky Peach, the beloved and now-defunct food magazine started by chef David Chang. Since this article ran, Tiu died at the age of 66. ~ RIP on behalf of the LA Taco community.

[dropcap size=big]I[/dropcap]n an L-shaped strip mall on the part of Sunset Boulevard that runs through Thai Town in East Hollywood is a restaurant called Jitlada: the Original Southern Thai Cuisine. On any given night, the wait list, on a clipboard that hangs next to the entrance, is usually long and might include Ryan Gosling, Drew Barrymore, or Matt Groening, who has drawn so many illustrations for Jitlada that an entire wall in the restaurant is dedicated to them. While you wait for your name to be called, you can visit the other shops in the mall: the marijuana dispensary, the Thai convenience store, the florist, the barbershop, the day spa.

When it is your turn, Sarintip “Jazz” Singsanong will take you inside and take care of you. Jazz owns the restaurant with her brother Suthiporn “Tui” Sungkamee, who is the chef. Once seated, you’ll likely be overwhelmed by the hundreds of dishes improbably crammed onto the few pages of the menu, at which point you’ll do well to turn to Jazz for help. She will recommend the delicately fried morning glory, one of Tui’s curries, and maybe one or two more of his southern Thai specialties, like deep-fried fish rubbed with fresh turmeric, the khao yam rice salad, the raw blue-crab salad mixed with papaya, or the soft-shell crab, fried and tossed with pungent sator beans. If she has the time and the ingredients, she might offer to make you her Jazz burger, a patty laced with garlic, palm sugar, and spices, presented on a giant lettuce leaf and topped with red chilies, special sauces, tomatoes, red onions, and Thai basil. The proper thing to do here is to listen to Jazz, to follow her lead.

A burger might be the last thing you’d expect to find at a southern Thai restaurant, but it is, in a lot of ways, perhaps one of the most LA things you could eat. Indeed, the story of Jazz, Tui, and Jitlada is as Los Angeles as the palm trees and the footprints at Grauman’s Chinese Theatre.

[dropcap size=big]J[/dropcap]azz and Tui come from a family of twelve children. Tui is the oldest, and Jazz is the third oldest, and the oldest daughter. They grew up in Nakhon Si Thammarat, a coastal province in southern Thailand about one hundred fifty miles from the Malaysian border. Garlic, turmeric, galangal, chilies, and makrut limes grew on their family’s properties, and they played in the shade of coconut and mango trees. There were fish and watercress in the surrounding canals and ponds. Their mother leased out their shrimp farm, and during some months, tenants would bring freshly caught shrimp along with the rent. Everyone in the family helped with the cooking. Tui, being the oldest, learned the earliest.

“I started at five years old,” he says. “Five years old. Going to Grandma’s house to peel garlic. And when I would run away to play, she would say, ‘Hey, Tui, come back. Sit with me,’ then give me more garlic to peel.”

At six, he would gather curry ingredients: lemongrass, galangal, those makrut lime leaves. At eight, he was in charge of making coconut milk, which required climbing trees to retrieve said coconuts. At fifteen, he was allowed to make curry himself.

When Tui was eighteen, he moved north to Pattaya, near Bangkok, and became a weekday tour guide. On the weekends, he cooked for friends, who loved his food so much that they urged him to open a restaurant. After seven years of listening to his friends’ pleas, he told them that he’d give the restaurant business a try if they found him a space. And that’s just what they did.

It was a small place, but not so small that he couldn’t make the coconut curries and seafood dishes he had grown up with. Business was slow, though—so slow that he initially held on to his day job and cooked in the evenings and on the weekends. His friends, afraid that he’d become discouraged and quit, came in every day. They probably didn’t need to worry: Tui is nothing if not patient and confident. He was convinced then, as he is now, that once people tried his food, they’d come back, with friends. Sure enough, he built such a following that by 1996, he had a mini empire of four restaurants, all in Pattaya.

[dropcap size=big]W[/dropcap]hile her brother ran his restaurant in Pattaya, Jazz was studying hospitality and hotel administration at a Bangkok University. In 1979, when she was twenty-four, she left for LA, joining her uncle who was already in the city. Like many other Thais who came to LA to pursue an American education, she enrolled at Los Angeles City College in East Hollywood, near the neighborhood that would eventually become Thai Town, and brushed up on her language skills.

“I didn’t speak English for nine months,” she says, “because I was scared. I understood everything, though.” She had a few odd jobs here and there before finding work at the Millennium Biltmore Hotel in Downtown LA.

Over the next few years, other family members, including her parents and several of her siblings, joined her in LA. Tui, though, didn’t move to the city until 1996, when he traveled there with his then-four-year-old daughter to visit his ailing father. The original plan was to stay for just about a month and then return to Pattaya, but his daughter had other ideas: she wanted to stay and continue going to school in LA. Tui decided that, for the sake of his daughter, they’d move to LA permanently. (The apple didn’t fall far from the tree: she now has her own Thai restaurant, Spicy Sugar, in Long Beach.)

He entrusted his Pattaya restaurants to a friend and picked up a job cooking at a Thai restaurant in Westwood, around thirty minutes from Thai Town proper. The clientele of college students and Westside residents wasn’t quite receptive to his specialties, and he looked for another location closer to East Hollywood. In 2006, he and Jazz got wind that Jitlada, a Thai restaurant in a strip mall in the heart of Thai Town, was for sale.

Jitlada opened in Thai Town in the late 1970s; Jazz remembers dining there when she came to LA. It became well known not just for “some of the city’s best Thai food,” as Ruth Reichl, then the restaurant editor of the Los Angeles Times, said in 1984, but also for its location: observers marveled at the seeming incongruity of having such terrific food in its particular setting. “Jitlada is the name of the Thai royal palace in Bangkok, but there is nothing palatial about the restaurant: it’s a simple, two-room place in a mini shopping mall,” Colman Andrews said in the New York Times in 1990. The Rough Guide to Los Angeles & Southern California in 2011 recommended the restaurant, but not before qualifying it with a note about its spot in a “dreary” mini mall.

Yet great strip-mall restaurants are (in LA, anyway) really no more unlikely than traffic on the 405. Their proliferation—and how they came to define LA eating over the past three decades or so—was spurred in large part by the passage of the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act and the 1973 OPEC oil crisis.

[dropcap size=big]P[/dropcap]rior to 1965, U.S. immigration policy was what you might consider an early version of Donald Trump’s proposed wall. It was, specifically, built around national-origin quotas that allotted the vast majority of visas to residents of northern and western Europe. Immigration from most Asian countries, meanwhile, was outright banned until piecemeal legislation in the 1940s and 1950s lifted the prohibition for some countries. Even then, the number of visas allotted to those specific countries was nominal.

The 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act poked holes in the wall. Among other changes, the act effectively replaced the national-origins requirements with a category-based system of admission that prioritized family reunification and skilled labor; it also set aside a certain number of visas to refugees. (The law had its less-fine moments: it strengthened a ban on LGBTQ individuals and imposed a limitation on immigration from the Western Hemisphere, impacting a regular stream of Latin American workers into and out of the United States.)

The law had a huge impact on Asian immigration to the United States, and particularly to LA. In 1960, there were 120,000 Asians in LA; by 1970, the population was 240,000; by 1990, 1.3 million, with the Korean, Indian, Chinese, and Filipino communities experiencing exponential growth between 1970 and 1990. Thais—many of whom were students in pursuit of an American education—also immigrated to LA in significant numbers: of the roughly 44,000 Thais who came to the United States during the 1970s, as many as 10,000 settled in LA.

The end of the Vietnam War in 1975 also brought “an influx of refugees from Southeast Asia to the United States” and to Los Angeles in particular, says Dr. Karen Tongson, an associate professor of English and gender studies at the University of Southern California, who also teaches courses in Los Angeles geography and food cultures of the American West.

The end of the war also coincided with the 1973 OPEC oil crisis, which spurred the closure of thousands of gas stations across the county (the Los Angeles Times estimated that of the 6,000 gas stations operating in the county in the mid-1970s, more than half had closed by 1991). Many of these stations were at intersections zoned for commercial use and had been built with one or two large driveways easily accessible by cars. Commercial builders were quick to figure out what they could build in those lots.

“With so many gas stations going out of business during the 1970s, developers saw an opportunity to create a business structure where people could pull in and out,” says Dr. Tongson.

The “business structures” that many developers chose to build were L-shaped buildings, usually with six to eight storefronts, often one story high but sometimes two, with a parking lot in the front and two driveways, to enter and exit. Developers liked to call them “convenience centers” to highlight their utilitarian purpose: you could park, drop off your dry cleaning, pick up cookies for your kid’s birthday, grab a doughnut for the drive home, and be on your way again. Developers also emphasized the centers as ways for budding entrepreneurs to get their start, particularly for those who couldn’t afford the higher rent prices in the larger indoor malls, or in spaces closer to Downtown.

'Being able to buy in at a strip mall affirmed that mythos for many immigrant communities.'

Many budding entrepreneurs turned out to be the new immigrants settling the city. In 1987, one developer with 125 strip malls estimated that he leased three-quarters of his space to recent immigrants. A good number of these immigrants turned to the business of food. “It was a way of importing certain experiences people had with creating their own food stalls or makeshift restaurants back home as a source of extra income,” Dr. Tongson says. Accessing the American dream of owning one’s space was also a strong factor in pulling immigrants toward starting their own businesses; as she says, “Being able to buy in at a strip mall affirmed that mythos for many immigrant communities.”

That mythos, of course, runs up against reality. As Dr. Tongson points out, these restaurants “are often cheek by jowl with remittance businesses”— money-transfer services —“where you see the realities of the poverty that exists in this global circulation of bodies, where you see the migrations and the people left behind through the remittances they send home.”

By the late 1980s, these myths and realities were playing themselves out in some two thousand strip malls in Southern California, and vocal opposition to the very existence of the malls grew. Homeowner associations and what was called the “slow-growth movement” saw the malls as part of a larger problem of overdevelopment; they also argued that the malls contributed to the “environmental ugliness” of the city. Xenophobia was coded, as it often is, as a safety concern: one member of the Friends of Westwood homeowners’ group fretted that the malls were “hangouts and places where criminal elements tend to congregate.”

As a result, the city of LA, plus several nearby cities in Orange County and San Diego, passed temporary moratoriums on strip-mall construction before enacting strict controls on their development, requiring builders to conform to specific landscaping parameters and to include a certain number of parking spots per square foot of retail space. But attempts to curtail the development were too little, too late. Strip malls had already become part of the landscape of the city, and so too had the immigrants who saw these structures not as blights to be eradicated but as opportunities to embrace.

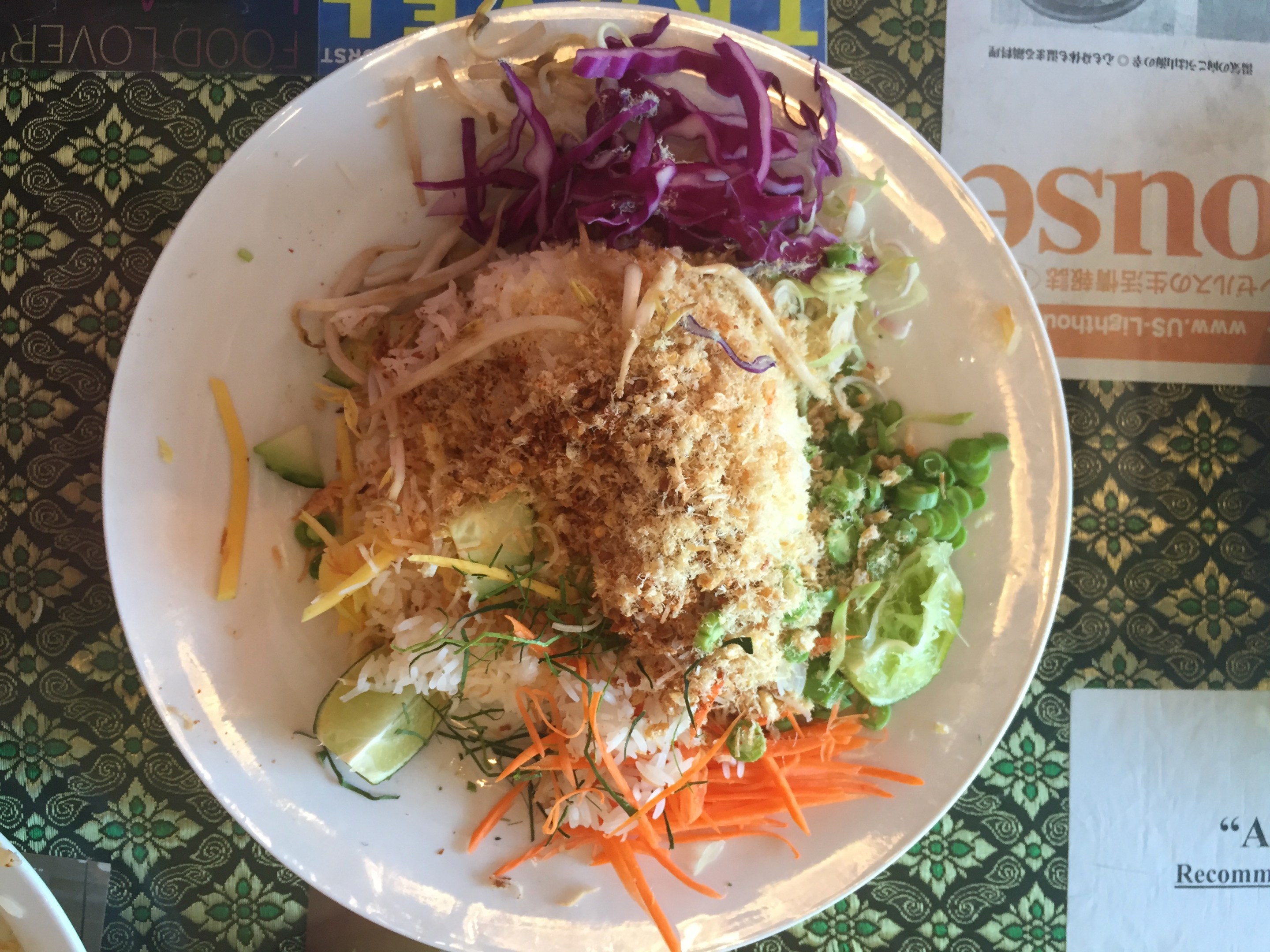

[dropcap size=big]W[/dropcap]hen Tui and Jazz took ownership of their strip-mall restaurant in 2006, they retained most of the original menu to avoid disappointing existing customers. Tui doesn’t recall many other southern Thai restaurants in Thai Town at the time, so he didn’t know if there would be a big demand for his specialties, which were added to the menu in an appendix that was written only in Thai script, with no English translations. That menu included his version of a khao yam, a searing medley of rice, dried shrimp, toasted coconut, lemongrass, and chilies tossed in a sauce called naam khoei; a salad of sliced mangoes, shredded coconut, cashews, lime juice, and dried shrimp; and kua kling, a dry curry of turmeric-infused shredded beef laced with chilies so spicy that it’s still one of the hottest dishes in the city.

Although the siblings garnered a small but loyal customer base among locals who loved spicy food, their first year was pretty rough nonetheless. “We didn’t have money when it started,” Jazz says. Her intention then was to “just help my brother, give him a hand.” She ended up becoming, among other things, hostess, manager, busser, and cook. They made two or three hundred dollars a day, and Jazz borrowed money and maxed out her credit cards to keep the restaurant afloat.

One day in early 2007, a visitor from Chicago happened to pick up Jitlada’s take-out menu at his hotel. He didn’t speak Thai, but he had been to southern Thailand, so his interest in the restaurant was piqued by the promise printed on the menu (“The very best Southern Thai food from Jitlada”). He came in and, over the course of his three-day visit, tried as much as he could. With Tui’s help, he worked out English translations for the dishes.

Three months later, Tui says, the visitor called to say he had “put the menu on the computer.”

'They said, ‘One day, Jonathan Gold will come.’ And I thought, Who is Jonathan Gold?'

Erik M., the online handle of the Chicago visitor, had posted a translated menu of Tui’s dishes on a Chicago food-focused site called LTH Forum. At the time Erik called Tui, the post had already been viewed one thousand times. Within days, it made its way over to the Los Angeles section of Chowhound. The active users of Chowhound trekked over to Jitlada, and soon Jazz was fielding orders from customers ordering directly off of Erik M.’s post, which they had printed out and brought with them to the restaurant. Chowhounders posted their own reports back on the site, and the Internet feedback loop kicked into high gear: a June 2007 post about Jitlada ignited a thread 112 replies deep.

As the restaurant became more and more popular, Jazz began to hear about a guy named Jonathan Gold.

“People were talking,” Jazz says. “They said, ‘One day, Jonathan Gold will come.’ And I thought, Who is Jonathan Gold? I didn’t know America had food critics, or people who write about food.” Customers told her that if Gold, the restaurant critic who was then writing for LA Weekly, came in, people would follow.

“I prayed to Buddha every day that Jonathan Gold would walk in,” she says. She had never met him and didn’t know what he looked like, so she turned to her customers for ideas. “I asked everyone about him,” she says. She continued to pray.

One day in 2007, not too long after Erik M.’s post, Jazz was at work and making the rounds, chatting up her customers, as she does. “Who is Jonathan Gold?” she remembers asking one particular customer.

That particular customer was, you guessed it, Jonathan Gold.

When Gold reviewed Jitlada in LA Weekly in August of 2007, he hailed it as “the most exciting new Thai restaurant of the year.” The day after, Tui arrived at the restaurant in the morning to prepare for lunch. Why are there so many people in front of our restaurant? he remembers thinking at the time. A small crowd was assembled, lingering outside the door, their cars filling up the parking lot. The review was in their hands. They were waiting for the restaurant to open.

“After that day,” Tui says, “more and more people came. They ate and posted more.” Indeed, food bloggers organized meet ups and trips to the restaurant, where they ordered en masse, photographed en masse, and posted en masse. In these scrappy, halcyon days before food news was filtered through well-capitalized food-media machines, these bloggers were, for many, the primary sources; if your blogroll in the past decade or so at anytime included Eating L.A., Gastronomy, or any other LA food blog, there was no way you did not read about Jitlada.

[dropcap size=big]I[/dropcap]t’s been more than a decade since Tui and Jazz took over Jitlada, and nine years since the reviews began flooding in. The parking lot of this “dreary” mini mall now has valet parking to accommodate the crush of cars in the evening. The southern Thai section of the menu is now in English as well as in Thai and, in case you don’t happen to have Erik M.’s post printed out, a little cheat sheet of Tui’s most popular dishes sits on each table. The walls have become more and more crowded with press clippings and awards and Matt Groening drawings. The number of dishes on the menu has ballooned into the hundreds, as Jazz and Tui have added dishes like crispy papaya salad and a yellow curry with pork belly and sator beans. Tui also created a “Dynamite Challenge,” which involves your choice of protein in a curry or mint-leaf sauce and your ability to tolerate a level of heat not found anywhere else in the city (if somehow you manage to finish it all, the dish is on the house).

If Tui’s cooking catapulted Jitlada onto the national food scene, Jazz has solidified it as an institution. “The customers, they are my family,” she says. And you don’t doubt for a second that she means it: she imbues the space with a charismatic, kinetic energy and takes care of you so well that it’s almost impossible to eat here without feeling like you’ve made a new friend. And like a good friend, she’ll have ice, cucumbers, and tomatoes at the ready to extinguish flames. She’ll remember she hasn’t seen you since you had your kid. She’ll insist you follow her outside to take a selfie.

And before you leave, she might slip you a container of a special sauce she just made. “For breakfast tomorrow,” she’ll say, before rushing back inside and leaving you to cradle your souvenir back to your car. You’ll peel out of the parking lot and head home, knowing that breakfast tomorrow is going to be great.

RELATED: The Rogue 99 ~ L.A. TACO's 2018 Essential Restaurants List